AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 11

Digital, cloud, and AI transformations are creating new offerings and business models. Fast-growing spaces and ecosystems are emerging at the intersection of existing industries. These transformations have been linked to a range of benefits for individuals, organizations, and societies.1,2 At the same time, there have been calls to address their environmental impact.3 A key example is the significant increase in energy consumption. Other developments include increased water use and the extraction of scarce minerals to support the cooling and constant renewal of the digital infrastructure that underpins these transformations.

Although environmental consequences are now on legislators’ radar, the challenge of targeted and effective regulation in the digital age is significant.4 Regulators often lack the skills and resources to effectively regulate and monitor the rapid and ongoing changes associated with digital and AI transformations. More participatory governance arrangements are needed, in which regulators engage in systematic dialogue with self-regulatory initiatives from the digital sector.

However, many digital fields are fragmented and still maturing. This can impede the collective action necessary for broader and more detailed self-regulatory initiatives to emerge. For instance, industry coordinating organizations are still inexperienced and may only represent firms from specific networks.

This article aims to help managers and policymakers understand how industrial players can overcome these difficulties. It draws on the Climate Neutral Data Centre Pact (CNDCP), which brought together a diverse group of data center operators to collaborate with the European Commission to limit the negative environmental impact of data centers,5 and details three key practices used to develop the pact: forging new relationships, leveraging existing templates, and advancing inclusive audit frameworks.

CNDCP

The CNDCP, which was set up in close collaboration with the European Commission, pledged to achieve climate neutrality by 2030. Frans Timmermans, former executive VP of the European Commission for the European Green Deal, explicitly expressed his support:

Today’s pledge from important parts of the data industry constitutes a promise to society and offers a welcome first step toward achieving our common ambitions for a smart and sustainable future.6

Pact members have committed to the European Green Deal, achieving greenhouse gas reductions that come with climate legislation, and leveraging technology to contribute to the ambitious goal of making Europe climate-neutral by 2050.

As is often the case in industry self-regulation,7 increased attention to sector regulation at the European level was an important trigger for the pact. In 2019, the newly installed von der Leyen European Commission administration outlined an ambitious climate agenda that could lead to stricter regulation for data center operators. Although the field was not against regulation, there were concerns that new legislation would not be well adapted to the day-to-day operations of data centers. Data center operators wished to engage in further dialogue with the European Commission, and to do this more collectively, the pact was launched at the beginning of 2021.

CNDCP Focal Areas

The pact comes with target setting, monitoring, and focal points for collaboration with legislators in several areas:8

-

Energy efficiency. Digital services will continue to grow, but the impact of this growth on energy consumption will be determined by the pace of energy-efficiency gains. The pact commits to high standards of energy efficiency. Legislators are urged to reduce administrative barriers and facilitate cooperation toward more efficient information and communications technology (ICT) systems.

-

Clean energy. The members of the pact are committed to meeting a significant proportion of the electricity needs of data centers with renewable energy. Members emphasize that the availability of renewable energy is a critical factor in realizing this goal.

-

Water. Many data center operators use water for cooling. Recognizing that water is becoming scarce, the pact sets standards for water conservation.

-

Circular economy. Data center operators plan to participate in the circular economy, an economic model that features prominently on political, governmental, and business agendas, particularly in Europe.9,10 The circular economy promotes sharing, lending, reusing, repairing, upgrading, and recycling in a closed-loop system that aims to maintain the maximum utility and value of products, components, and materials in production and consumption. Pact members are committed to establishing, normalizing, and advancing circular economy business models and practices. The focus is on repairing and reusing equipment to reduce consumption. In this area, the pact calls on the EU to support policy frameworks that focus on and promote circular methods.

-

Circular energy. Pact members agreed to explore the recovery and reuse of heat from new data centers. Heat recovery includes circular energy systems that use heat from a facility as a sustainable source for homes and buildings. Recovery can reduce emissions by displacing other energy sources used for heating and play a role in making Europe climate-neutral by 2050. However, optimizing heat recovery requires a policy framework that values the environmental benefits of recovered heat and reduces regulatory barriers to developing these projects.

-

Reporting/governance. To increase transparency and support the quality of self-regulation,11 the pact will meet with the European Commission twice annually to review its status. Furthermore, in its second year, an audit framework was developed, and participants are required to certify adherence.

To focus efforts, some targets (e.g., the ones for energy efficiency) were set right after the pact’s initiation. Others, such as those on water use, were defined later or are still under development, including circular economy and circular energy.

3 Key Practices

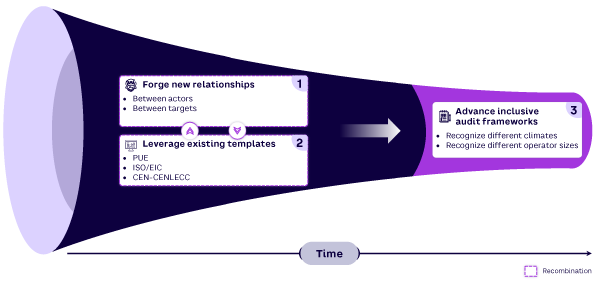

Today, more than 100 operators have joined the pact. But how did this collective action take root given the fragmentation and dynamics in the field? Researching the pact yielded three supporting practices (see Figure 1) that are largely in the spirit of recombination, a mechanism designed to underpin a wide range of innovation processes.12,13

1. Forge New Relationships

The intention of the European Green Deal was to understand the climate benefits of existing laws and introduce new legislation on the circular economy, building renovation, biodiversity, agriculture, and innovation.14 The EU had already developed a code of conduct for data centers through its Joint Research Centre (in 2008). This voluntary code encouraged data center operators to use best practices to reduce energy consumption and promote sustainability. The industry feared that this code of conduct could become law under the Green Deal without sufficient input from the sector.

Two groups separately initiated a response and found each other at industry-wide events. The first was the European Data Centre Association (EUDCA), which predominantly represents industry participants with a co-location business model. The other group was CISPE (Cloud Infrastructure Services Providers in Europe), which represents companies with a cloud provider business model. They decided to work together to expand their reach, even though their business models compete with each other. The new relationship was formalized through the pact as a new organization run by representatives from both networks, which themselves had existed for less than a decade.

In addition to forging a relationship between the two networks, the pact also adjusted the industry’s energy-efficiency target areas. The 2008 Data Centres Code of Conduct focused primarily on increasing energy consumption by data centers and the resulting environmental, economic, and energy security impacts.15 The pact was the first to conflate this with a broader set of targets that became more prominent over time, such as water and circularity.

Addressing a broader set of issues supports the transition from carbon to climate neutrality but also complicates it, as targets can interact in non-synergistic ways. For example, some data centers evaporate water for cooling, and although removing it contributes to water targets, the energy for cooling must come from somewhere else, increasing energy use. These conflicts have been embraced and are now seen as targets for continuous innovation.

2. Leverage Existing Templates

Institutional innovations such as the pact do not appear out of nowhere, and indeed, the pact appears to have drawn from several existing templates. For example, it used the power usage effectiveness (PUE) ratio to concretize the area of energy efficiency. PUE was introduced and promoted by The Green Grid, a nonprofit organization of IT professionals, beginning in 2007.16 PUE is the ratio of the total energy consumed by a data center to the energy delivered to the computing equipment. The pact understands the limitations of PUE and is committed to helping develop a new efficiency metric, but it’s using PUE for now because it is well-known in the IT infrastructure sector and thus makes it easier to get smaller players on board.

The pact also sought to align its auditing framework with existing international standards. The aim was to lower the cost of reporting by avoiding duplication and recognizing existing relevant certifications. The pact provided a comprehensive mapping of how its newly developed areas and targets correspond to a variety of partially overlapping European (CEN-CENLEC) and international (ISO/EIC) standards. This was further extended to US standards to accommodate operators with a global footprint.

3. Advance Inclusive Audit Frameworks

The pact also saw the wisdom of advancing inclusive audit frameworks, including recognizing the diversity of European climates in which data centers are built. Colder climates result in less need for cooling, which accounts for around 30% of the energy consumed by a data center. Therefore, it is easier to achieve better PUE levels in Finland than in Greece. Pact members agreed that by 2025, new data centers operating at full capacity in cool climates will have to meet an annual PUE target of 1.3, while those facing warmer outside temperatures will have to meet a PUE target of 1.4.

Pact members committed to meeting with the European Commission twice a year to review the initiative’s status and introduced a performance assessment. To lower the threshold for participation and maintain inclusiveness, self-assessment was introduced for small data center operators. Large data center operators, which generally have more resources, must be assessed by an external assessor.

Taken Together

This article discussed collective self-regulation in the wake of Europe’s push to combine digital and climate efforts. Collective action can be challenging for industry participants because digital spaces tend to be fragmented and complex. We zoomed in on the data center space to identify three practices that stand out in collectively setting up elaborate initiatives that go beyond broad codes of conduct and can therefore be better measured and monitored. This framework can easily be applied to initiatives in other digital spaces.

References

1 Falcke, Lukas, et al. “Digital Sustainability Strategies: Digitally Enabled and Digital-First Innovation for Net Zero.” Academy of Management Perspectives, 18 March 2024.

2 Kolk, Ans, and Francesca Ciulli. “The Potential of Sustainability-Oriented Digital Platform Multinationals: A Comment on the Transitions Research Agenda.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Vol. 34, March 2020.

3 Péréa, Céline, Jessica Gérard, and Julien de Benedittis. “Digital Sobriety: From Awareness of the Negative Impacts of IT Usages to Degrowth Technology at Work.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 194, September 2023.

4 Cusumano, Michael A., Annabelle Gawer, and David B. Yoffie. “Can Self-Regulation Save Digital Platforms?” Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 30, No. 5, October 2021.

5 The information for this article largely comes from CNDCP archival data, including interviews with pact insiders and observers. I am grateful to pact insider Ben Maynard for acting as a sounding board during the writing of this article.

6 “Climate Neutral Data Centre Pact.” Climate Neutral Data Center, accessed November 2024.

7 Cusumano et al. (see 4).

8 “Self Regulatory Initiative.” Climate Neutral Data Centre Pact, accessed November 2024.

9 De Pascale, Angelina, et al. “The Circular Economy Implementation at the European Union Level. Past, Present and Future.” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 423, October 2023.

10 European Commission. “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A New Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe.” EUR-Lex, 11 March 2020.

11 Gunningham, Neil, and Joseph Rees. “Industry Self-Regulation: An Institutional Perspective.” Law & Policy, Vol. 19, No. 4, October 1997.

12 Crouch, Colin. Capitalist Diversity and Change: Recombinant Governance and Institutional Entrepreneurs. Oxford University Press, 2005.

13 Harper, David A. “Innovation and Institutions from the Bottom Up: An Introduction.” Journal of Institutional Economics, Vol. 14, Special Issue 6, December 2018.

14 Simon, Frédéric. “EU Commission Unveils ‘European Green Deal’: The Key Points.” Euractiv, 11 December 2019.

15 European Commission Joint Research Center et al. “2017 Best Practice Guidelines for the EU Code of Conduct on Data Centre Energy Efficiency — Version 8.1.0.” Publications Office of the European Union, 2017.

16 Brady, Gemma A., et al. “A Case Study and Critical Assessment in Calculating Power Usage Effectiveness for a Data Centre.” Energy Conversion and Management, Vol. 76, December 2013.