AMPLIFY VOL. 36, NO. 12

Kanina Blanchard draws on the findings from a graduate education course that takes a curated approach to self-exploration. She emphasizes the need for leaders to move beyond traditional metrics and recognize their accountability to communities and the broader world. Blanchard reframes responsible decision-making as a journey, highlighting reflection, emotional exploration, and learning from experiences. The article stresses the importance of individual transformation and tangible choices, encouraging continuous learning, humility, and resilience in the pursuit of responsible decision-making.

Leaders of all ages and at all stages of their careers are being asked to make better, more responsible decisions. This involves seeing themselves as part of the communities in which they live and work and recognizing that they are accountable to more than just themselves and their organizations.1

Needing to develop dimensions of not just competence, but also character and judgment, individuals in formal, informal, emerging, and existing leadership roles are realizing they must step up to address the challenges of our time.2 Whether it’s rampant corruption, growing inequality, local or large-scale climate change disasters, global pandemics, wars, or displacement, the challenge remains — how?3 How can leaders make more responsible decisions in a world where economic metrics predominantly determine success in both work and life?

Thanks to new research, a graduate education course at a leading Canadian business school is reframing responsible decision-making. Rather than focusing on theoretical discussions or creating a checklist of to-dos, the course “Leading Responsibly” at the Ivey Business School teaches individuals to become more responsible by helping them unpack their lived experiences.

Character as the Foundation

The work of researchers and practitioners who recognize that teaching competencies alone are insufficient underpins Leading Responsibly.4 Skills that individuals can do and or learn to do have traditionally been the focus of leadership education. This myopic approach helped create the crisis in which the world finds itself: a world with skilled leaders primarily measured on their ability to deliver on profit and growth.

Without education that challenges students to aspire to become responsible global citizens, they are not prepared to engage. Without education that emphasizes character building, students don’t learn to develop humility or humanity. Unless they learn how to build enough courage to make choices that confront conventional norms, they do not step in and challenge them.

Leading Responsibly begins with students exploring the importance of character in leadership. They are encouraged to move past cognitive knowledge and tap into the emotions that emerge as they try to improve their decision-making (decisions that consider the needs of all stakeholders, even those without an economic connection to them or their organizations).

Students share their feelings of failure and success, as well as memories of the critical role of others in their efforts to date. The journey toward making more responsible decisions cannot be solitary, so students listen to their classmates’ stories about “trying to be responsible” and begin to understand the necessity of developing a support network.

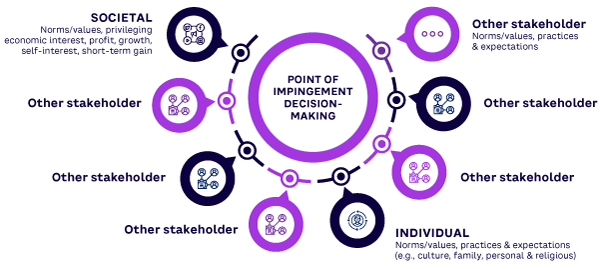

Choosing a decision-making path that focuses on “we” not “me” involves reframing responsibility, not as a badge of honor or a framed certificate, but a way that understands how one’s competencies and character dimensions interconnect to support purpose-driven judgement (see Figure 1).5 Doing so helps one strengthen resilience, challenge conventional norms, prioritize values, and become more responsible in day-to-day decision-making.

Making responsible decisions, then, is not about becoming something or someone. Rather, it is a choice to be made in the moments when disparate, often paradoxical, pressures bear down. It is in these moments that character matters most.

Making Good Judgments & Responsible Decisions

Making good judgments or decisions as a leader is defined as being able to draw on relevant information and make a critical analysis of facts in a timely manner, appreciate broader and more complex contexts, pivot when confronted with new information or situations, reason effectively in uncertain or ambiguous situations, and see beyond the obvious and into the heart of challenging issues.6

Recognizing that having good judgment is the result of leaders not only developing their competencies, but also dimensions of their character, students discuss how such a journey involves commitment to achieving challenging goals. This requires prioritizing differently, engaging with a variety of stakeholders, and recognizing that sacrifices may be required. Responsible decision-making is grounded on the three components of exemplary leadership: character, competencies, and commitment (see Figure 2).7

Feeling Responsibility in Decision-Making

That “responsibility” in leadership matters is not in question. That responsibility requires leaders to elevate priorities beyond themselves, their organizations, and economic metrics is also not in question. The questions that loom large include:

-

What can I possibly do?

-

What impact can I really have?

-

Am I too low in the organization to do anything?

-

What about the risks of not putting profit first?

Drawing on learnings from Leading Responsibly, participants who wish to make more responsible decisions are encouraged to follow Gandhi’s advice: “Be the change you want to see in the world.” Moving away from judging others and toward self-reflection stirs action on the one thing in the world we have control over: our character. Making more responsible decisions requires commitment and involves taking risks. However, the skills it involves can be learned.

Moving past the rational approach to decision-making in which people use facts, information, analysis, and a step-by-step process, students are encouraged to reflect on moments in time when they found themselves at the point of impingement (see Figure 3).8,9 It is at these pressure points that we experience conflicting norms and values (e.g., juggling the pressure to increase profit and support growth in the short term while adhering to norms and values around long-term environmental sustainability goals).

Instead of learning theories, students are asked to engage with their memories, their senses, and their experience of feeling these tensions. Talking about how it feels to be responsible offers a deeper understanding and the possibility of change. Participants in the course describe feeling stuck or trapped, needing to put a stake in the ground, or feeling ill at the point of impingement. A few said they felt as though they were drowning.

Unpack Your Relationship with Responsibility

Research shows that having the courage to reflect on how and why responsibility matters personally is an essential step to making more responsible decisions. Considering one’s origin story related to responsibility leads to reflection on events dating back to childhood, education, and/or work experience.

Some students recall learning about responsibility in a formal setting (school, religious classes, books, exposure to other cultures, or extracurricular activities). Others recollect memories from informal, unplanned (and often unwelcome) experiences they had to navigate (significant life changes, traumatic events).

Participants share how the loss of a parent led them to step into roles of responsibility early in life, how their upbringing (volunteerism, religious practice) resulted in normalizing “doing good works” or giving back, and how failing to take responsibility in their work resulted in harm to others. Reconnecting with our first memories of responsibility ignites not only interest and curiosity, but a drive to learn more.

Invest in Support Systems & Networks

Striving to make more responsible decisions is a journey to take with others. The importance of building a support system and creating a network of like-minded people is discussed at length in the course, in part because choosing to make responsible decisions can pit one against normalized expectations (e.g., making money). There are risks, challenges, and possible negative consequences to taking a more responsible path.

As part of this exploration, students identify individuals, institutions, and resources from their past and present. Some recognize the possibility of seeking the support of counselors or psychologists to help them understand their experiences of the tensions associated with being at the point of impingement.10 Others note how their partner, a friend, a colleague, or members of their family have been a consistent presence, standing with them and accepting any consequences that may arise. Some talk about a book or an author whose work provides motivation to face the tensions associated with challenging the “normal” way of doing things.

Preparation & Practice

Embracing responsible leadership as a journey rather than a destination opens the door to recognizing that it is a strategic endeavor. It requires negotiation and compromise, such as knowing when and where to push, how and when to lobby stakeholders, and even when to recognize the time and context isn’t right. In discussions, students share stories of focusing on listening skills, building connections, and understanding the viewpoints of stakeholders with vastly different experiences and priorities.

Being more responsible in decision-making also requires building dimensions of character (e.g., temperance, humanity, and justice). Choosing to emphasize long-term, nonfinancial priorities (e.g., diversity, equity, and inclusion or the environment) means being deliberate, measured, and patient, as well as finding ways to calibrate your expectations of yourself, your organization, and others. It requires sacrificing time, energy, effort, and short-term gains.

Preparation and practice are central to this endeavor. This includes engaging with humility, being realistic about the context in which one works and one’s positionality, and being prepared for negative consequences such as slower promotion or even job loss. Being prepared personally and professionally (including mental and financial health), having a support system, being willing to “fail forward,” and cultivating a growth mindset are all key.

Bringing Learning to Life

Participants are encouraged to express their learnings in a form they can share and use on their journey. Some write stories or poetry, often drawn from their feelings about being responsible or irresponsible, to serve as a reminder or touchpoint. Some draw or adapt pictures; others create an object that holds meaning for them. These physical objects embody participants’ goals and serve a variety of personally relevant functions. In sharing and discussing their artifacts, students are able to express a narrative. They can identify the dimensions of their character they continue to build, skills and competencies they wish to learn or improve, and the origin of their commitment.

Key Insights

After several years of teaching the course, we’ve gained insight into multiple issues relevant to educators and mentors. For example, young professionals regularly express fear of “rocking the boat” too early in their careers. Counteracting this is a matter of reinforcing the idea that having a responsible mindset is the first in a spectrum of actions they can take. Being strategic involves considering an array of next steps and possible consequences, including engaging in conversation with members of a safe network, researching best practices, and identifying and offering alternatives. Although whistleblowing or quitting are also options, it is important to present these as being on the far end of the spectrum, not a go-to.

We have also discovered the importance of self-disclosure. Asking others to do the emotional, challenging work related to building character dimensions and understanding the consequences of taking the road less traveled requires vulnerability from the educator or mentor. Practicing humility, sharing your own story, discussing how you have invested in a support system, and relating how you have succeeded and failed forward set the stage for a safe, collaborative learning environment.

Finally, we learned to meet participants where they are. Experiential learning is predicated on individuals making meaning from what is offered, and life/work circumstances impact the pace, timing, and depth of individual engagement. As educators and leaders, imagine yourselves as gardeners creating a safe, healthy place for growth. You must cultivate the space and actively feed the ideas you see germinating. Allow each seed to follow its own path. Some will sprout immediately; others will take longer. Appreciate the efforts made, knowing that, for some, it may only be in the longer term that these ideas and practices will blossom.

Conclusion

Until society and organizations shift so that profit/growth is only one measure of success, leaders will continue to face challenges, risks, and barriers as they strive to make more responsible decisions.

Although change at the individual level is only a piece of a much larger puzzle, it is worth pursuing. If responsibility matters to you, invest. Be clear about your purpose. Recognize that your commitment will involve sacrifice and choice. Be strategic about preparing and planning, with an emphasis on the long term. Be intentional about transforming your perspective, and focus on your actions, behaviors, and decisions: this is where responsibility emerges and is demonstrated. Responsible action requires doing, not just knowing. It involves engaging purposefully, having prepared for the challenges and issues that may emerge. Knowing the right thing to do is very different than taking action.

Making good judgments is inherently challenging and requires developing one’s competencies and character. Doing so under pressure and in situations where you may be testing conventional norms and expectations requires commitment.

Leaders must be prepared to face the challenges and complexities that accompany alternative approaches. They must recognize that this magnitude of change requires relationships with like-minded individuals and a strong support system.

Understanding why responsibility is a priority for you is central to generating personal definitions of important concepts, including what success and failure look and feel like, what your nonnegotiables are, and how you will develop the skills and competencies to engage strategically. Investing energy and attention in continuous learning, remaining humble and able to learn from failure, and developing a resilient mindset are all key to making good decisions at the point of impingement.

References

1 Maak, Thomas, and Nicola M. Pless. “Responsible Leadership in a Stakeholder Society — A Relational Perspective.” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 66, May 2006.

2 Crossan, Mary, Gerard Seijts, and Jeffrey Gandz. Developing Leadership Character. Routledge, 2016.

3 “Warning Over Half of World Is Being Left Behind, Secretary-General Urges Greater Action to End Extreme Poverty, at Sustainable Development Goals Progress Report Launch.” Press release, United Nations (UN), 25 April 2023.

4 Crossan, Mary, et al. “Developing Leadership Character in Business Programs.” Academy of Management Learning & Education, Vol. 12, No. 2, July 2012.

5 Crossan, Mary M., et al. “Toward a Framework of Leader Character in Organizations.” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 54, No. 7, December 2016.

6 Crossan et al. (see 5).

7 Seijts, Gerard, and Karen MacMillan (eds.). Leadership in Practice: Theory and Cases in Leadership Character. Routledge, 2018.

8 Uzonwanne, Francis C. “Rational Model of Decision Making.” In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, edited by A. Farazmand. Springer International Publishing, 2016.

9 Blanchard, Kanina. “Is Responsible Leadership Possible? Exploring the Experiences of Business Leaders, Educators, and Scholars.” PhD diss., Western University Graduate & Postdoctoral, 2020.

10 Blanchard (see 9).