Establishing and upholding a company’s purpose is not confined to grand gestures — it consists of actions and decisions both large and small. It encompasses how you greet your colleagues at the start of the day; your organization’s governance structure; and the types of shareholders, clients, and suppliers in which your company engages. The following five principles can help guide deliberation about corporate purpose.

1. Encourage Open Dialogue

Successful deliberations about purpose require open dialogue. Real talk about what is important (independent of direct interests) is critical for developing a shared purpose. Everyone’s opinion is worth listening to. There are no privileged positions and no experts, only reasoned ideas.

Open dialogue is only possible when we agree on certain rules. This is one of our biggest challenges. Can we listen to someone with opposing opinions and work with him or her to develop a solution that feels good? Conflict resolution requires serious interpersonal skills and deep reflection by every individual. Governance mechanisms are important here, but in the end, the people who work with them decide how they are used.

2. Support Deliberation with Corporate Laws & Rules

Laws, corporate rules, and procedures should support deliberation mechanisms. For starters, that means they cannot hinder open dialogue. Beyond that, we must understand that the law is not about defending interests; rather, it should help stakeholders develop their purposes together.

Management expert Mary Parker Follet wrote: “Law cannot decide between purposes, set their various values, and secure interests. Its task is to allow full opportunity for those modes of activity from which integrating purpose may arise, and such purpose tends to secure itself. The function of law is not merely to safeguard interests; it is to help us to understand our interests, to broaden and deepen them.”

Follet was active in the debate about corporate governance in the 1920s, together with John Dewey. They worked to prevent a strict definition of the purpose of the company in US law because they believed it would hinder open dialogue.

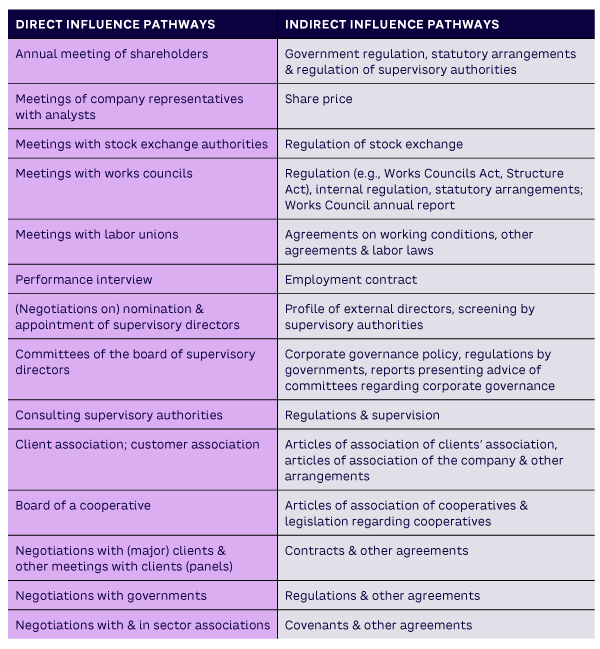

It is time we take this principle in corporate law seriously again. When lawyers suggest that a CEO weigh their words carefully, real dialogue goes out the window. In Europe, there is a serious tradition of stakeholder dialogue mechanisms. Works councils, advisory boards, cooperative governance structures, and foundation-owned companies all tend to allow room for deliberation and stakeholder dialogue (see Table 1).

Here, direct and indirect influence pathways can be relevant. In the former, companies and stakeholders influence each other in direct dialogue. In the latter, regulation acts as an intermediary. Attention to these pathways makes clear that the purpose of the company tends to be the subject of a variety of governance mechanisms. Purpose develops in every interaction between a company and its stakeholders, not just at the annual meeting.

For example, the successful Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk is a foundation-owned company listed on the stock market. This shows it’s possible to be market-driven while investing in R&D, taking social projects seriously, and making shareholders happy.

3. Use History as a Touchstone

We can look to the past to see how individuals dealt with similar tensions before us. Current issues are rooted in historical developments — and so are the solutions.

We tend to underestimate the role of history, although many of us use earlier experiences to argue against or favor a certain solution. History is reflected in companies’ economic positions. Stakeholder issues are also rooted in history, and this quickly becomes apparent during crises. Every stakeholder dialogue should start with a reflection of history. When we agree on the root cause, we can discuss solutions that could work for everyone involved.

4. Let Individual Responsibility Guide You

We must be guided by our individual responsibility but able to relate to other perspectives. We cannot hide behind our role and place in society or our lawyers. We are responsible for certain tasks. We must be guided by individual responsibility and relate that to the responsibility of others. This means making choices between possible stakeholders and understanding that it is not about what your lawyer says is your responsibility but about how you develop your own responsibility.

5. Be Integrative

Integration is the task of executives and stakeholders. This is a very personal moment: you have to integrate your feelings (negative and positive) and cognitive understandings into what you do in your daily life and connect with others. The real fun — and I would argue the fulfillment of professional life — is that after serious deliberation with stakeholders, a solution develops that promises a new future for you and your company. Deliberation processes should enable executives and corporate stakeholders to integrate their interests so that decisions are better than the individuals themselves could have thought of before the process started, rather than weak compromises.

[For more from the author on this topic, see: “Developing Corporate Purpose Through Deliberation.”]