AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 9

The human tendency toward black-and-white thinking is intensifying. It’s apparent in political debate, of course, but also frames how we look at business. Since most companies are profit-driven and free to interpret their own social responsibility, they tend to develop deliberation processes that push them toward purposes that are beneficial to the company in the long term. This process of deliberation, in which small gestures are decisive, is structured in governance mechanisms.

This polarization is a critical issue. After the 2019 American Business Roundtable explicitly said that companies should serve all their stakeholders, some US states tried to block corporate social responsibility and sustainability policies because they can threaten shareholder interests.

This article does not delve into political discussions or discuss theoretical aspects about the purpose of a company. Instead, it uses insights from the US and Europe to explain that the purpose of the company as a profit-oriented organization develops through deliberation processes. The outcome of that process may be that political action is necessary to safeguard a company’s financial interests. Likewise, a social issue must sometimes be considered, regardless of the cost to the company’s bottom line.

Developing a successful company requires a dialogue with the right people at the right moment and creating the right amount of tension between various interests. The organization’s deliberation processes and an understanding of the responsibilities of executives drive this.

This article does not aim to defend any specific shareholder/stakeholder perspective. Rather,

we discuss how companies organize deliberation processes and whether these processes enable the integration of the right stakeholder interests.

Importantly, establishing and upholding a company’s purpose is not confined to grand gestures — it consists of actions and decisions both large and small. It encompasses how you greet your colleagues at the start of the day; your organization’s governance structure; and the types of shareholders, clients, and suppliers in which your company engages.

Deliberation & Corporate Purpose

The basic definition of “deliberation” (thoughtful and careful decision-making) has received a lot of attention in philosophical and religious traditions. In the US, pragmatists paid a lot of attention to deliberation processes (see sidebar “Pragmatism as an Intellectual Response to the US Civil War”). In Europe, the work of German philosopher Jürgen Habermas in the 1970s brought increased attention to deliberation.

Currently, the concept is most often seen in corporate governance. For a long time, economist Milton Friedman’s assertion that the “business of business is business” dominated economic debate.1,2 With the Business Roundtable arguing that companies should strive for an economy that serves all Americans, governance scholars are trying to develop an alternative to Friedman.

So what are the best governance mechanisms to give a variety of stakeholders control?

Business leaders from any country can learn a lot from Europe as they seek to develop robust governance mechanisms. For example, banks in the Netherlands have never been controlled solely by private shareholders. In Dutch banks, complex deliberation systems have been developed that have been successful in the last century.3 Employees, clients, and the government all have a role in the governance of banks.

Pragmatism as an Intellectual Response to the US Civil War

Pragmatism is a philosophy that can be seen as an intellectual response to the fierce polarization that led to the US Civil War.1 A group of men, some with experience in the war, formed the Metaphysical Club in the 1870s to develop an approach in which experience and action were valued over dogmas and authority. They had backgrounds in law, history, theology, philosophy, and other humanities.

Pragmatists laid the foundation for American intellectual life at that time, establishing fields such as psychology (William James) and education (John Dewey). They focused on practical experience and action and were strongly inspired by social workers in US cities, where many migrants suffered from poverty.

Practitioners such as Jane Addams and Mary Parker Follet developed social practices and developed the foundation for business schools. Dewey established a primary school with Addams, welcoming various cultures and backgrounds. Follet is seen as one of the founders of management science, along with Chester Barnard.2 The dominance of pragmatism ended in the 1950s. Its questioning attitude toward reality could not compete with the promises of positivist social science, which suggested answers to all social questions.

1 Menand, Louis. The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America. MacMillan, 2002.

2 O’Connor, Ellen S. Creating New Knowledge in Management: Appropriating the Field’s Lost Foundations. Stanford University Press, 2011.

Individual Responsibility: Integration is Key

Chester Barnard, one of the founders of management theory, argues that integrating a variety of interests is the critical responsibility of an executive. In The Functions of the Executive (long a standard book at business schools), he outlines an approach to deliberation in which managers reflect on their norms and the norms of their stakeholders and then work with the stakeholders to develop these norms further.4

Fortunately, Barnard has been recently rediscovered, and scholars are once again looking for an integrating, normative perspective.5 How can business school students be trained as responsible professionals who integrate various disciplines, such as finance, marketing, strategy, sales, and HR, into sustainable solutions for all?

Following Barnard, executives should develop deliberation processes in which integration of a variety of norms gets critical attention. They should focus on small things, including symbols, ideas, and gestures because they often make the company. For example, the Apple logo stands for much more than technical specifications. The values that the Apple logo stands for are visible in almost all the company’s actions.

5 Principles for Deliberation: Big Companies Consist of Many Small Gestures

Aristotle pointed out that most issues don’t have a clear right or wrong answer and that the difficulty is finding a path in between. For example, if we want sustainable societies, it is not good to completely forbid fossil fuels or to promote them. Instead, we must ask: how can we deal with fossil fuels so they will improve society as a whole? We face a similar conundrum when it comes to large-scale changes in business. When companies change too fast, it usually leads to serious economic problems. Similar problems occur when they do not change fast enough.

Pragmatism makes these big questions personal. We are caged in our thinking, our norms, and our experiences. Dialogue and open communication are the only approaches that enable us to develop ourselves and our society. Questioning is the gate to development because it enables us to understand our norms and those of others.

Here, small gestures can help jump-start productive discussions because they help us understand the underlying norms of various people that need to be further developed. Developing norms together enables progress. This implies significant tensions between individuals, but workable solutions must be found. When we can agree on small things, we develop this understanding toward a shared understanding of bigger issues toward a common purpose.

The following five principles can help guide deliberation about corporate purpose.

1. Encourage Open Dialogue

Successful deliberations about purpose require open dialogue. Real talk about what is important (independent of direct interests) is critical for developing a shared purpose. Everyone’s opinion is worth listening to. There are no privileged positions and no experts, only reasoned ideas.

Open dialogue is only possible when we agree on certain rules. This is one of our biggest challenges. Can we listen to someone with opposing opinions and work with him or her to develop a solution that feels good? Conflict resolution requires serious interpersonal skills and deep reflection by every individual. Governance mechanisms are important here, but in the end, the people who work with them decide how they are used.

2. Support Deliberation with Corporate Laws & Rules

Laws, corporate rules, and procedures should support deliberation mechanisms. For starters, that means they cannot hinder open dialogue. Beyond that, we must understand that the law is not about defending interests; rather, it should help stakeholders develop their purposes together.

Management expert Mary Parker Follet wrote: “Law cannot decide between purposes, set their various values, and secure interests. Its task is to allow full opportunity for those modes of activity from which integrating purpose may arise, and such purpose tends to secure itself. The function of law is not merely to safeguard interests; it is to help us to understand our interests, to broaden and deepen them.”6

Follet was active in the debate about corporate governance in the 1920s, together with John Dewey. They worked to prevent a strict definition of the purpose of the company in US law because they believed it would hinder open dialogue.

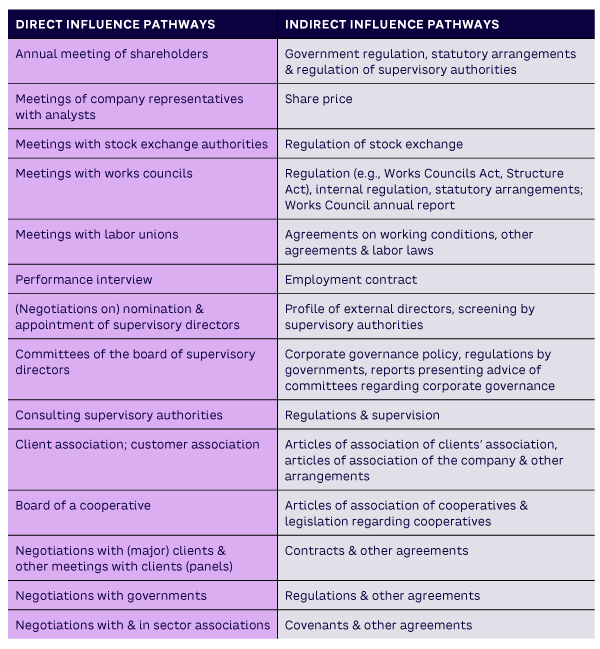

It is time we take this principle in corporate law seriously again. When lawyers suggest that a CEO weigh their words carefully, real dialogue goes out the window. In Europe, there is a serious tradition of stakeholder dialogue mechanisms.7 Works councils, advisory boards, cooperative governance structures, and foundation-owned companies all tend to allow room for deliberation and stakeholder dialogue (see Table 18).

Here, direct and indirect influence pathways can be relevant. In the former, companies and stakeholders influence each other in direct dialogue. In the latter, regulation acts as an intermediary. Attention to these pathways makes clear that the purpose of the company tends to be the subject of a variety of governance mechanisms. Purpose develops in every interaction between a company and its stakeholders, not just at the annual meeting.

For example, the successful Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk is a foundation-owned company listed on the stock market. This shows it’s possible to be market-driven while investing in R&D, taking social projects seriously, and making shareholders happy.

3. Use History as a Touchstone

We can look to the past to see how individuals dealt with similar tensions before us. Current issues are rooted in historical developments — and so are the solutions.

We tend to underestimate the role of history, although many of us use earlier experiences to argue against or favor a certain solution. History is reflected in companies’ economic positions. Stakeholder issues are also rooted in history, and this quickly becomes apparent during crises. Every stakeholder dialogue should start with a reflection of history. When we agree on the root cause, we can discuss solutions that could work for everyone involved.

4. Let Individual Responsibility Guide You

We must be guided by our individual responsibility but able to relate to other perspectives. We cannot hide behind our role and place in society or our lawyers. We are responsible for certain tasks. We must be guided by individual responsibility and relate that to the responsibility of others. This means making choices between possible stakeholders and understanding that it is not about what your lawyer says is your responsibility but about how you develop your own responsibility.

5. Be Integrative

Integration is the task of executives and stakeholders. This is a very personal moment: you have to integrate your feelings (negative and positive) and cognitive understandings into what you do in your daily life and connect with others. The real fun — and I would argue the fulfillment of professional life — is that after serious deliberation with stakeholders, a solution develops that promises a new future for you and your company. Deliberation processes should enable executives and corporate stakeholders to integrate their interests so that decisions are better than the individuals themselves could have thought of before the process started, rather than weak compromises.

Conclusion

Companies are profit-optimizing organizations. As such, they integrate the interests of a specific set of stakeholders in a specific way within deliberation processes.

The critical responsibility of executives and their non-executive board members is to organize these deliberation processes so that integration can occur, and a specific set of stakeholders can align with the corporate executives. Strong deliberation processes integrate various interests, enabling executives and stakeholders to integrate their opinions toward a new perspective of reality. This perspective enables a company to develop further.

A company is only as strong as its deliberation processes, which are unique. Novo Nordisk is different from Tesla; Patagonia is different from Shell. But all of them need strong connections with stakeholders that share some underlying values with them, and this must be properly communicated over time. Every executive must develop their own strategy, and to understand these strategies, deliberation processes should get more attention than they currently do in our polarized societies.

References

1 Friedman, Milton. Capitalism and Freedom. University of Chicago Press, 1962.

2 Friedman, Milton. “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits.” The New York Times, 13 September 1970.

3 De Graaf, Frank Jan, and J.W. Stoelhorst. “The Role of Governance in Corporate Social Responsibility: Lessons from Dutch Finance.” Business & Society, Vol. 52, No. 2, February 2010.

4 Barnard, Chester I. The Functions of the Executive. Harvard University Press, 1938.

5 O’Connor, Ellen S. Creating New Knowledge in Management: Appropriating the Field’s Lost Foundations. Stanford University Press, 2011.

6 Follett, Mary Parker. Creative Experience. Longmans, Green and Co, 1924.

7 De Graaf, Frank J., and Cor A.J. Herkströter. “How Corporate Social Performance Is Institutionalised Within the Governance Structure: The Dutch Corporate Governance Model.” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 74, January 2007.

8 De Graaf and Herkströter (see 7).