AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 9

It is surprising, and often disconcerting, to observe a disconnect between what a company professes its purpose to be and the activities it engages in. The notion that pursuing one’s purpose requires you to not engage in activities that do not align with purpose seems straightforward, yet we frequently observe just that.

Sometimes the disconnect between actions and purpose is stark. Take Wells Fargo, which states its purpose this way: “With more than 150 years of experience, we’re focused on helping you figure out the financial solutions for every stage of your life. We offer convenient ways to help you manage your money, protect your finances, and reach your financial goals.”1

Despite this, in 2016, under pressure to meet aggressive sales targets, Wells Fargo employees created millions of bank accounts and credit card applications without customer consent, in clear violation of the stated purpose. “What were they thinking?!” one might exclaim. The answer most likely is “they weren’t,” perhaps because when the sales numbers started looking good, there were no systems in place to pump the brakes, so everyone simply went on doing what they felt needed to be done.

In this article, we propose that an essential element of scaffolding purpose is empowered refusal — a way of saying no to organizational activities and pursuits that do not align with your purpose, no matter how attractive they might seem. We discuss the hidden trade-offs in pursuing purpose, provide three key reasons organizations might pursue opportunities that are not aligned with their purpose, and reveal why it is so easy to stray from purpose and engage in purpose-diminishing activities. We then offer a nuanced understanding of empowered refusal by describing three different kinds of no and a framework for implementation.

The Missing No

According to Ratan Tata, former CEO of the Tata Group, purpose is “a spiritual and moral call to action; it is what a person or company stands for.” The power of articulating purpose lies in providing employees with a clear sense of direction, a set of shared priorities, and the inspiration to go the extra mile in service of purpose-driven goals, which should ultimately be good for profit.2

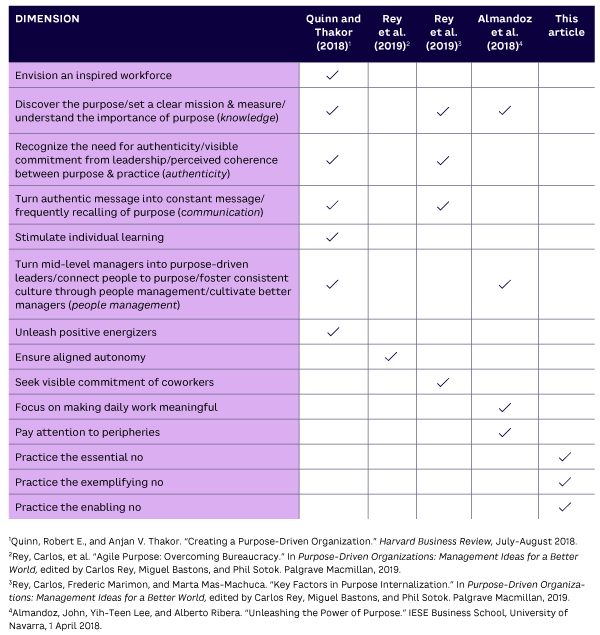

Table 1 summarizes key insights offered by researchers and practitioners on what needs to be done to create and sustain purpose in organizations. Notably missing from this list is the ability to say no to purpose-diminishing decisions, activities, and engagements.

Empowered Refusal

Prior research describes empowered refusal as a way of saying no that stems from the identity and underscores the value of an empowered no in both interpersonal and self-regulatory contexts.3,4 This research demonstrates that empowered refusal facilitates relationship management, reputation management, and goal pursuit.

In an organizational context, purpose is akin to identity.

We describe empowered refusal as a way of saying no that aligns with the organization’s purpose. The central thesis of current research is that to operate with a singularity of purpose requires every individual in the organization to have clarity about which actions and decisions align with that purpose and which do not.

The goal of empowered refusal is to be true to espoused organizational values that are reflected in purpose. As such, empowered refusal is an essential skill that organizations need to develop to align their actions and decisions with purpose.

Implementing the ideas in Table 1 is an excellent starting point for leaders committed to driving purpose in their organizations, but we don’t feel it is enough. We underscore the importance of matching espoused values (purpose) with enacted values (decisions and actions) by fostering a culture that empowers individuals to wield the power of no in service of scaffolding purpose.

The Hidden Trade-Offs in Pursuing Purpose

What you don’t do determines what you can do.

— Tim Ferriss, lifestyle guru5

When an organization articulates its purpose, it must consider an inherent trade-off. Committing to a purpose implies that (1) you have to engage in purpose-driven activities without distraction, and (2) you have to give up all purpose-diminishing activities, no matter how exciting and enticing they might be.

In our research, we have identified three overarching reasons why it is easy to allow purpose-diminishing activities to occur or make non-purpose-driven decisions instead of saying an empowered no:

-

Culture of cooperation. Cooperation with others is a commonly held and highly valued social norm. In an interpersonal context, saying no to the requests and invitations of others is often viewed to be a less favored response with negative consequences.6 Organizations are composed of people, so by a similar logic, there is also widespread reluctance in organizational settings to say no to the ideas and initiatives of others. We believe there are two main reasons why individuals say yes when they should say no. First, they fear saying no to others’ ideas because they worry about the rejection of their own ideas later. Given the informal quid pro quo that exists in the reality of organizational life, it's easier to say yes than to say no to the proposals of others. Second, people are afraid that saying no can have negative consequences. Naysayers are often seen as unlikeable and poor team players, making them less likely to be chosen for desirable promotions, lucrative transfers, or exciting projects. Both concerns are diminished with empowered refusal, because empowered refusal makes it clear that a no is not stubborn naysaying or a rejection of others’ ideas, but instead a strategic response that aligns people and the organization to purpose.

-

Fear of missing out (FOMO). Organizations often fear missing out on the latest thing, often without carefully evaluating whether and how the new thing fits with purpose. Indeed, the lure of the new is so deeply embedded in organizational culture that we often measure progress by the adoption of cutting-edge innovation. For example, although AI is a critical technology for most organizations, it is important to think through how to use AI to enhance purpose instead of blindly jumping on the AI bandwagon. Making it a practice to view any new opportunity through a purpose-driven lens can reduce FOMO.

-

Misaligned and short-term incentives. The exciting part of the purpose journey is defining and communicating it. The less exciting part is the detail-heavy work of aligning operating mechanisms with it. This includes performance metrics and incentives. If these are not updated to reflect the purpose, leaders and employees will see the purpose as “good on paper” and continue to act in ways that could be purpose-diminishing. It is easy to get lost in this chasm between strategy formulation and strategy implementation without the power of no.7

How Empowered Refusal Upholds Purpose

Given that empowered refusal is a way of saying no that gives voice to organizational values and reflects its purpose, it is critical to recognize the nuanced situations that call for different kinds of no to effectively scaffold purpose. The following three types can help any organization steer clear of purpose-diminishing activities.

1. The Essential No

It may seem obvious that an organization should say no to anything that is clearly contradictory to its stated purpose. A useful exercise for organizational leadership is to not merely define purpose, but also to articulate the activities, decisions, and initiatives that do not align with purpose. Executive coach Marshall Goldsmith calls this the “do not do” list.

As authors Robert Quinn and Anjan Thakor observe: "When a company announces its purpose and values but the words don’t govern the behavior of senior leadership, they ring hollow. Everyone recognizes the hypocrisy, and employees become more cynical."8

When an organization hesitates to exercise the essential no, it spells a death knell for purpose. Unfortunately, there are many prominent examples of organizations that did not say the essential no with costly consequences, including the aforementioned Wells Fargo.

Let’s consider Volkswagen, with corporate values that say: “Upright, regulation-compliant conduct is critically important to the success and resilience of the Volkswagen Group.” Yet in 2015, the US Environment Protection Agency (EPA) revealed that Volkswagen had violated the Clean Air Act by installing illegal software into diesel vehicles. The software made the cars appear to comply with environmental standards during testing while emitting pollutants far exceeding legal limits. It is clear that neither the leaders nor the engineering and manufacturing teams of Volkswagen invoked the essential no to steer clear of the temptation to circumvent EPA rules.

Consider Purdue Pharma, which said its purpose was to be “a pioneer in developing medications for reducing pain, a principal cause of human suffering.” In 2020, Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to criminal charges related to marketing OxyContin, the addictive painkiller. Penalties reached roughly US $8.3 billion. The company marketed the opioid to more than 100 doctors suspected of illegal prescriptions and lying to the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).9

This is an instance where not just those in the organization but many in the broader ecosystem (physicians, drug dispensers, and management consultants) did not say the essential no to practices that were starkly contrary to the stated purpose.

2. The Exemplifying No

An exemplifying no is often a bold or unconventional decision made by a leader that signals commitment to purpose. When Indra Nooyi was CEO of Pepsi from 2007 to 2019, she transformed Pepsi with her “Performance with Purpose” strategy focused on financial, human, environmental, and talent sustainability.

In describing that transformation, she said: “Taking bold actions early is critical for showing the organization that the purpose-driven strategy is not just the flavor of the day. Three things will send a clear message: creating high-profile leadership positions and filling many of them with outsiders; overturning decisions that would have made it through in the ‘old days;’ and letting some people go.”

One of the examples Nooyi mentions relates to overturning a decision that would have made it through in the old days. She recalls: “Another action that communicated volumes was a late-in-the-game decision to call off a major new product launch.… Just days before the planned launch, the product came to the notice of a senior executive who was not comfortable that the company would introduce a highly caffeinated snack that children might consume. He stopped its development, despite the costs that had already been incurred….”

Another difficult decision involved letting people go. This decision demonstrated that the purpose-driven strategy was not just the flavor of the day but an enduring commitment. She reflected, “Critics will always emerge, especially in the upper echelons of an organization. It’s important to involve them and engage in a transparent dialogue with them, pointing to the existential threat that the company may face tomorrow. It’s equally important to incorporate their legitimate concerns in implementing the strategy. However, if detractors aren’t converted within a reasonable period of time, they should not be allowed to continue to serve on the management team.”10

We believe that the exemplifying no is a critical tool that leaders can rely on to demonstrate commitment to saying no to purpose-diminishing activities.

3. The Enabling No

The essential no and the exemplifying no largely depend on senior leaders’ choices and actions. The enabling no offers all stakeholders in the organization (employees, suppliers, customers) permission to say no in service of purpose. The rationale behind the enabling no is that purpose should not be the responsibility of a special few; it should be embodied in the actions of everyone in the organization who believes in it and is eager to bring it to life.

Take Toyota’s famous “Jidoka” or “Stop the Line” culture, in which any operator could stop the production line by pulling a cord when they noticed an abnormality. Toyota instilled purpose in every employee. There was no need for reporting, escalating to superiors, or waiting for directions. If an abnormality was observed, operators had the authority (and responsibility) to stop the line. This is an example of enabling no that makes Jidoka (automation with human touch) a living reality.

The principle of subsidiarity posits that matters should be handled at the most decentralized level such that embedding subsidiarity in purpose results in employees and other stakeholders having the autonomy and support to make purpose-driven decisions when necessary.11 We borrow from Josh Bernoff and Ted Schadler’s notion of HERO (highly empowered and resourceful operatives) employees who, with the guidance and help of the organization, can be the ones who carry out purpose-driven activities and monitor operations and actions to ensure that purpose-diminishing initiatives are nipped in the bud.12

The enabled no can also be used to empower customers. Take Patagonia’s full-page advertisement in The New York Times on Black Friday in 2011 that said, “Don’t Buy This Jacket.” The goal was to encourage consumers to say no to excessive and wasteful consumption and to consider the environmental impact of their purchases. The advertisement also promoted sustainability and the idea of reuse, recycle, reduce.

PLEASE

To put empowered refusal into practice, we offer an easy-to-remember implementation formula (PLEASE) for using the three shades of no to scaffold purpose:

-

Plan (for the essential no). Right at the start, define a few essential “nos” and communicate them along with the purpose message. It will clarify what purpose is and is not to the organization.

-

Look (spot opportunities for the exemplifying no). Actively look for opportunities to deploy the exemplifying no. If they do not seem to exist, it is likely that the purpose is not clear enough or is not understood by all levels of the organization.

-

Encourage (offer permission for the enabling no). Be an evangelist for the purpose and communicate it to all stakeholders: employees, partners, customers, and suppliers. Ask employees to articulate what purpose means for them and give them permission to say no to activities not aligned with purpose.

-

Act (with courage and commitment). Make bold and visible decisions that say no with a sense of urgency. A reluctant no is almost the same as a resigned yes.

-

Spread (share stories with passion). Make the “stories of no” part of a broader narrative on purpose. Spreading these widely and telling them frequently will help make the purpose meaningful for the organization.

-

Embed (instill the capability). Monitor decisions to step away and ensure that all three shades of no are being exercised. Their combined power can build a strong, sustainable scaffold for purpose.

Conclusion

We believe that organizations benefit when no is not viewed as a bad word but a necessary one. When all three types of no (essential, exemplifying, and enabling) are exercised, their power increases exponentially. A powerful and virtuous cycle is created that propels purpose forward when:

-

Employees and customers trust that the organization’s natural and immediate response to anything that goes against the purpose is an emphatic no.

-

Employees see leaders making tough decisions, including saying no to what would have been acceptable before.

-

HERO employees across all levels believe in their ability to say no when they observe things that could derail the purpose.

-

Partners and industry peers respect the organization’s purpose and want to join forces to say no to business as usual.

References

1 ”Why Wells Fargo.” Well Fargo, accessed September 2024.

2 Birkinshaw, Julian, Nicolai J. Foss, and Siegwart Lindenberg. “Combining Purpose with Profits.” MIT Sloan Management Review, 19 February 2014.

3 Patrick, Vanessa M., and Henrik Hagtvedt. “‘I Don’t’ Versus ‘I Can’t’: When Empowered Refusal Motivates Goal-Directed Behavior.” Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 39, No. 2, November 2011.

4 Patrick, Vanessa. The Power of Saying No: The New Science of How to Say No That Puts You in Charge of Your Life. Sourcebooks, 2023.

5 Ferriss, Tim. “The Not-To-Do List: 9 Habits to Stop Now.” Tim Ferriss blog, 16 August 2007.

6 Patrick (see 4).

7 Tawse, Alex, Vanessa M. Patrick, and Dusya Vera. “Crossing the Chasm: Leadership Nudges to Help Transition from Strategy Formulation to Strategy Implementation.” Business Horizons, Vol. 62, No. 2, March-April 2019.

8 Quinn, Robert E., and Anjan V. Thakor. “Creating a Purpose-Driven Organization.” Harvard Business Review, July-August 2018.

9 Gunderman, Richard. “Oxycontin: How Purdue Pharma Helped Spark the Opioid Epidemic.” The Conversation, 19 April 2016.

10 Nooyi, Indra K., and Vijay Govindarajan. “Becoming a Better Corporate Citizen.” Harvard Business Review, March-April 2020.

11 Hollensbe, Elaine, et al. “Organizations with Purpose.” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 57, No. 5, September 2014.

12 Bernoff, Josh, and Ted Schadler. “Empowered.” Harvard Business Review, July–August 2010.