AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 8

Sixteen percent of the world’s population (1.3 billion people) are disabled.1 Disabled people are twice as likely to live in poverty than nondisabled people. In fact, a recent report by the United Nations (UN) showed that disabled people face an average of 20 percentage points difference in multidimensional poverty and employment.2 For some disabilities, employment rates are in single or low two-digit figures.3 Access to education remains severely restricted, if not entirely absent, in many regions. Many workplaces, recreational areas, and government buildings are inaccessible, and information is often not available in formats that disabled individuals can use. Stigma and prejudice are rampant.

A look at the latest UN report on disability and sustainable development doesn’t paint a better picture. Thirty percent of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) linked to disability aren’t on track, and 14% have worsened and won’t be met unless progress accelerates by two to 65 times, depending on the indicator.4

Alongside the rest of the disability community, I, as a blind professor, often wonder about this. We are roughly one in five people: why are we still so invisible? The statistics alone should spur urgent action. Most corporate equality, diversity, and inclusion programs have not fully (and, frankly, often hardly) woken up to the full spectrum of disability.

How is it that many products and services remain inaccessible to disabled customers?5 Why must we meticulously plan to find accessible restaurants or travel companies so we know we can enjoy our time and not get refused, discriminated against, or have our mobility equipment broken? Why do we face daily microaggressions at work and in public, often leading to isolated lives? And why is it deemed okay for employers, businesses, and the public to question and even dispute someone’s disability status or ask deeply personal questions about medical conditions or a stranger’s sex life?

The marketplace is disabling for my community.6 It’s 2024: why is ableism (discrimination of people based on differences in minds and bodies) still a thing?7 How can ableism be tackled to create a world where disabled people experience inclusion? How can we inspire people to see this as their purpose? How can purpose help?

This article argues that vulnerability can act as a key catalyst for positive contagion, bringing individuals’ purpose to the forefront and motivating others to embrace vulnerability and drive change.

What Is Disability?

The problem starts with the word “disability.” Many people avoid using this word in favor of words such as “differently abled,” “special needs,” “people of dedication,” and even “superheroes.” This is a problem because not using the word disability implies that it is a bad word, something to be ashamed of and only whispered about in dark corners. People’s negative perception of the word speaks to negative societal views on disability.

In truth, disability is not a bad word. It’s not a bad thing, either. Disability is a word that describes a situation and something many feel pride about.

Disability isn’t a monolithic concept. Traditionally, the medical model of disability has dominated: disability is a deviation from an arbitrarily defined “normal” body or mind. According to this view, disability is something to be fixed, aiming to make the disabled body as close to an able-bodied one as possible.

The disability rights movement has championed a different perspective: the social model of disability. This model argues that disability arises not from an individual’s physical or mental differences but from societal barriers, be they physical, virtual, or relational. For instance, if all information were available in screen-reader-accessible formats, if wayfinding systems were prevalent, and if public transportation announced stops, a blind person like me would be far less disabled. The issue lies not in our bodies, but in a world that is not designed for us.

Other models highlight the psycho-emotional work of disabled people to deal with daily challenges and their struggles to gain human rights. Even more so, the affirmative model of disability celebrates our diversity in minds, bodies, and bodyminds and embraces disability pride.8

Most people and businesses view disability through the lens of the medical model. This perspective contributes to 1.3 billion people being overlooked or hushed rather than celebrated as part of the rich diversity of humanity. It also explains the ongoing debate and frequent censoring and policing of disabled people when they refer to themselves as disabled. Many disabled people are regularly told: “Don’t use that word; you’re not disabled.”

Many disabled people deliberately choose identity-first language to indicate their alignment with the social model of disability (that the world they live in isn’t designed for them). They don’t refer to other people as “able-bodied.” Instead, they use the term “nondisabled” or, more recently, “not-yet-disabled,” acknowledging that many people will experience disability with age.

I would never dictate how anyone should refer to themselves nor should nondisabled people and businesses. For this article, I use the term “disabled people” to align with the social model. However, I recognize that others within the community prefer “person with a disability.”

Understanding that disability means different things to different people is as crucial as respecting their choice of identity-first or person-first language. These terms carry significant meaning — more than many nondisabled people realize.

Disability & the Pandemic

My research journey began in a field far removed from disability; I was a social entrepreneurship scholar. In 2017, I began volunteering in disability organizations and switched my research focus to disability a year later. I found my purpose in it. I experienced (and still do) ample ableism. For example, I was told at the age of 11 to give up plans of attending university or having a meaningful career. Today, I engage in unpaid and paid work that gives me purpose.

This purpose became even clearer at the start of the pandemic. Reading social media posts and reports from disabled journalists about what was happening to disabled people shook me to the core. I read reports about do-not-resuscitate orders being signed on behalf of disabled people, guide dogs being kicked and hit by members of the public (because of fears they transmitted the virus), and disabled people being unable to access care, food, and other basic needs. This was happening while nondisabled people talked about how they finally understood what being disabled was like. They didn’t. This told me I needed to do even more. I needed to find a way to create a platform to amplify others’ voices and bring these stories to nondisabled people. I needed allies who shared the purpose of disability inclusion.

My work started with a research project funded by the British Academy as part of a special research grant scheme. Between August 2020 and September 2022, Oana Branzei from the Ivey Business School in Canada and I followed 24 disabled workers in the UK. Our participants represented diversity regarding their disability, gender identity, race/ethnicity, LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and others) identity, relationship status, educational background, and/or whether they were employed or self-employed/entrepreneurs.

For two years, they wrote, spoke, or drew diaries for us, and we regularly talked to them over Zoom. We captured their experiences of starting new jobs, being made redundant, being furloughed, starting or quitting a part-time degree, breaking off long-term relationships, processing grief, experiencing suicidal episodes, comforting colleagues, and being afraid/anxious/joyful/excited. It was one of the most eye-opening and emotionally engaging research projects I have ever conducted. Being able to share (to a degree) the lives of 24 strangers taught me much about disability and ableism.

The most striking thing was the efforts our participants undertook to make meaning.9 For example, Herbie talked about how his colleagues called him a robot because of his autism, and Annemarie had to send out 1,000 applications to get an entry-level job, even though she had been an executive before she became disabled. Like many other disabled individuals, she is overqualified for the job she managed to secure. Pink talked about how her nondisabled colleagues leaned on her for comfort because she knew what it was like to live in a world not designed for her. In fact, many of our participants engaged in this type of emotional labor — there is a great deal of unseen work disabled people do to “fit” in a nondisabled world.10

Vulnerability Lessons

Vulnerability came through clearly in the study and others I’ve conducted since. It’s present in social media creators and public speeches. Notably, our participants weren’t just vulnerable with me; they behaved similarly with others in the workplace, at industry events, and through their social media activity. They came to recognize the impact this has on others, and many used their vulnerability to find their purpose. This intrigued me.

Recent research centers on the role of compassion in social entrepreneurship.11 This work showcases how events in a social entrepreneur’s life shaped their decision to engage in activities to create a better future for others in a similar situation. In my work with disabled people, compassion plays a big role, but vulnerability plays a bigger one.

The crucial difference is that vulnerability for disabled people isn’t a periodic experience; it’s a part of life. What I’m referring to is not voluntary vulnerability (where someone chooses to be vulnerable) but situations where people are made vulnerable and even made to share vulnerability. It’s both choice and coercion — sometimes not even distinguishable in the moment of experienced or shared vulnerability.

4 Truths

What can we learn from disability, vulnerability, and purpose? Much, but the four points below are essential:

-

Disability is too hidden. It is frequently the missing feature in diversity considerations, product and service design, workplace organization, process and operations management, and other parts of business. Disability needs to be made visible. Companies that fail to accommodate and embrace the disability community miss out on a vast talent pool and a significant customer base. It’s time businesses woke up to this reality and took meaningful steps toward genuine inclusivity. The future of work and society depends on it.

-

Disabled or not yet, vulnerability allows us to delve deep within ourselves to discover our “true” purpose. This doesn’t need to be connected to potentially traumatic experiences, but it will likely relate to something we feel strongly about. Without vulnerability, we cannot find what that is.

-

Vulnerability is not about fishing for praise or pity, it is about being open about the ups and downs of life. It thus requires authenticity from those sharing their vulnerability as part of their own purpose, supporting others in finding purpose, and receiving vulnerability. Change can’t happen if the recipients of vulnerability simply respond with pity or praise; they must reflect and link these to their own experiences and identify what their role could be in spreading positive change so that barriers are broken down and triumphs multiply.

-

Vulnerability acts as a service to others, helping them tap into their purpose if they haven’t yet discovered or fully embraced it. Leaders can promote and support positive attitudes toward disability and other topics by being vulnerable themselves and by creating environments that allow others to safely express their vulnerability. This aligns with the increasing discussions about safe zones or safe spaces. These spaces are less about avoiding conflict and more about establishing clear rules that govern conversations. In these spaces, people can openly express their feelings and thoughts with the knowledge that the other people in the “room” have the tools they need to explain why they object to, feel uncomfortable about, or are offended by certain statements.

When Purpose Becomes Contagious

For an inclusive world to become a reality, these four lessons must spread. But how can companies tap into vulnerability if they don’t have any disabled staff or people who are comfortable being openly vulnerable due to a lack of perceived safety?

I believe the idea of positive contagion can help us with this. From consumer research, I borrowed the idea that behaviors, products, and services linked to something perceived as positive can spread like viruses.12 Several studies have showcased the positive contagion effect within leadership in global companies or looked at the role of hopeful leaders in their organization’s success.13,14

This led me to consider how the positive contagion effect could be created without personal interactions. This is crucial to supporting organizations that have no or only a few disabled staff, to reduce the burden of educating nondisabled people about disabled people, and to create widespread change toward urgently needed disability inclusion.

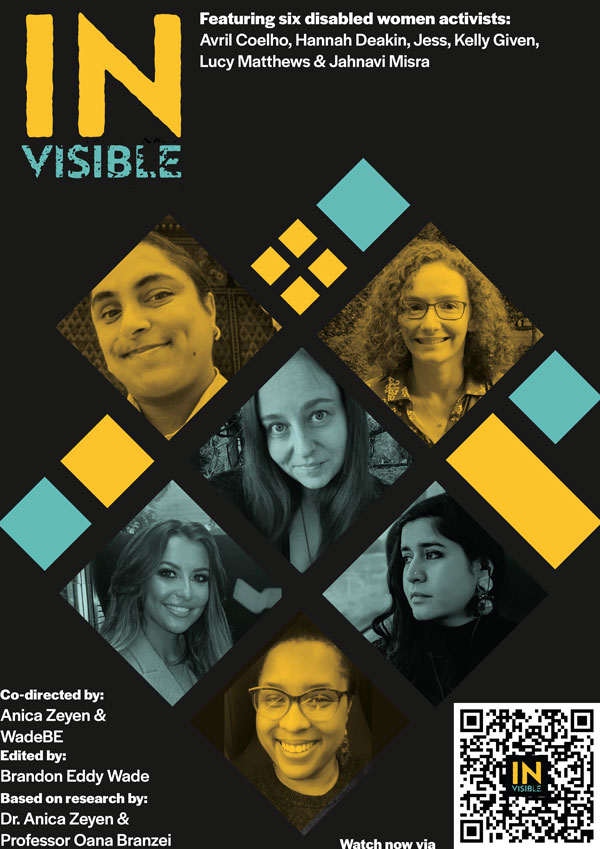

I decided to create a documentary that featured forms of vulnerability in an accessible way. I co-directed it with filmmaker WadeBE (see Figure 1). It features six disabled UK women of varied racial, economic, and class backgrounds with different sexual orientations, family situations, and ages. Each came forward willing to be vulnerable in front of strangers and cameras. Each has invisible disabilities, sometimes in addition to visible disabilities. The 26-minute documentary is called Invisible, not only because the protagonists have invisible disabilities, but because their experiences and identities often went unnoticed.15

The six women (Avril, Hannah, Jahnavi, Jessica, Kelly, and Lucy) share their experiences during the pandemic and beyond. They open up about their struggles, their triumphs, and a great deal more. Their stories are deeply personal and emotional. They are also sometimes painful or full of pride, joy, and hope. (Their full interviews are available on YouTube.16)

Their purpose comes across most poignantly when asked why they chose to take this step into high visibility. Jessica says: “I wanted to do this so that anyone who wonders if they are alone, feels less alone.” She continues: “I don’t know how to describe it. If I would have been able to see, or experience really what a potential future may look like, I would’ve felt more able to dream for a future of myself.” Her purpose is to ensure that other disabled Black LGBTQ+ people don’t feel the same hopelessness regarding their future. She talks about how homophobia, racism, and ableism were (and sometimes still are) her companions. She also wants everyone to know that she has a job she likes, is finally learning how to play the piano, and is happy with her wife, Hannah. She did not think such a life was possible.

She is not alone. Kelly was diagnosed with autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in her mid-20s. She is passionate about human rights, especially for disabled women, and managed to land her dream job: an internship with the UN in New York. She was the runner-up in a Channel 4 UK reality TV show called “Make Me Prime Minister,” where she again chose to be vulnerable by allowing the crew to film her autistic meltdowns. Kelly found relief in her diagnosis: it helped her understand herself, find her purpose, and no longer live in her car.

Avril had to leave her political party due to harassment. She struggles to pay for her household expenses but is constantly fundraising on behalf of others. She advocates for those marginalized in her community while balancing regular medical appointments for her epilepsy and other conditions.

Hannah spent multiple years in a hospital bed. She is now an electric wheelchair user with chronic pain and energy-limiting conditions. In the film, she proudly shares that she got her first job at the age of 30, something she thought would never happen. She devotes the limited energy she has to her job as an accountant and to blogging about her experiences as a way to advocate for more accessibility.

Lucy faces severe mental health challenges, including bipolar disorder. She openly discusses these issues, not only in our documentary but in a newsletter to her entire organization, where she talks about depression, severe anxiety, and her daily life beyond the pandemic. Similarly, Jahnavi experienced a combination of racism and ableism and used the pandemic as an opportunity to publish her first book.

For some of these women, disability played no role. For others, their disability and its invisibility made their challenges and subsequent triumphs much greater. All of them share their pride in persevering, in “still being here,” and in their deep purpose: ensuring that the world they leave behind is a much more inclusive one.

We screened Invisible for the first time right before the International Day of Disabled Persons (which is on 3 December). Part of the audience was in tears. While filming, my crew and I often sat in rapt silence, hardly even daring to breathe.

Although I was amazed by all six women, I wanted to make sure the film focused on their vulnerability. It was important not to turn it into what disability activist Stella Young calls “inspiration porn.” She uses this term to label depictions of disabled people in which they get praised and put on pedestals for simply existing or for activities that wouldn’t lead to praise if a nondisabled person did it (e.g., people being amazed that I can cook and that I do it without chopping off my fingers).17

I felt it was important to show that their disability brings these women joy and pride just as much as it brings them anxiety and struggles. Not everything in their lives is good or bad because of their disability; sometimes, disability is just the backdrop against which their lives occur. More importantly, I wanted to lift the invisibility cloak off these moments of dark and light. These women are extraordinary not because they are disabled, but because they showcase why vulnerability is nothing to be ashamed of — rather, it requires courage and is very powerful. They took something that others sometimes coerce them to do and made it their own, on their terms. To me, this is strength.

Invisible has been shown in university classrooms and companies around the globe. It has also been viewed by more than 1,000 people on YouTube. In anonymous surveys, viewers shared with us how the film reshaped their view of disability. Many told us they plan to go back into their workplaces and companies and ensure disability becomes a key consideration in decisions. Avril, Hannah, Jessica, Jahnavi, Kelly, and Lucy were willing to be vulnerable, and this vulnerability is spreading and creating change, just as though it were contagious.

It is time that 1.3 billion people become visible to all of us. Disability can teach us much about diversity within humanity, and it holds many lessons about purpose and vulnerability. It demonstrates that being vulnerable on one’s own terms can create change and spread like a positive contagion.

Of course, as with real viruses, this only works through exposure. It is on everyone to ensure that leaders, managers, colleagues, clients, and customers are exposed to disability (vulnerability) to help spread and create an inclusive world for all of us. Watch films like Invisible, engage disabled public speakers, watch disabled content creators, listen to members of your disabled staff employee networks (or facilitate the founding of one), and educate yourself.

Ensure disability is omnipresent in all decisions made. Listen to vulnerability, be vulnerable yourself, and work together as allies. Amidst all of this, never forget the disability movement slogan: “Nothing About Us Without Us.” Include us — don’t be part of making us invisible.

References

1 “Disability.” World Health Organization (WHO), 7 March 2023.

2 United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). “Disability and Development Report 2024: Accelerating the Realization of the Sustainable Development Goals by, for, and with Persons with Disabilities.” Reliefweb, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 11 June 2024.

3 Ryan, Frances. Crippled: Austerity and the Demonization of Disabled People. Verso, 2019.

4 UN DESA (see 2).

5 Lourens, Heidi, and Anica Zeyen. “Experiences Within Pharmacies: Reflections of Persons with Visual Impairment in South Africa.” Disability & Society, March 2024.

6 Higgins, Leighanne, Katharina C. Husemann, and Anica Zeyen. “The Disabling Marketplace: Towards a Conceptualisation.” Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 40, No. 5-6, April 2024.

7 Wolbring, Gregor. “The Politics of Ableism.” Development, June 2008.

8 Zeyen, Anica, and Oana Branzei. “An Introduction to Disability at Work.” In Routledge Companion to Disability and Work, edited by Oana Branzei and Anica Zeyen. Routledge, 2024.

9 Zeyen, Anica, and Oana Branzei. “Disabled at Work: Body-Centric Cycles of Meaning-Making.” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 185, March 2023.

10 Branzei, Oana, and Anica Zeyen. “An Emergent Theory of (Dis)ability at Work.” In Routledge Companion to Disability and Work, edited by Oana Branzei and Anica Zeyen. Routledge, 2024.

11 Yitshaki, Ronit, Fredric Kropp, and Benson Honig. “The Role of Compassion in Shaping Social Entrepreneurs’ Prosocial Opportunity Recognition.” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 179, June 2021.

12 Argo, Jennifer J., Darren W. Dahl, and Andrea C. Morales. “Positive Consumer Contagion: Responses to Attractive Others in a Retail Context.” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 45, No. 6, October 2018.

13 Story, Joana S.P., et al. “Contagion Effect of Global Leaders’ Positive Psychological Capital on Followers: Does Distance and Quality of Relationship Matter?” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 24, No. 13, January 2013.

14 Norman, Steve, Brett Luthans, and Kyle Luthans. “The Proposed Contagion Effect of Hopeful Leaders on the Resiliency of Employees and Organizations.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2, Winter 2005.

15 TEND Project. “Invisible — Documentary About 6 Disabled Women Activists.” YouTube, 2 December 2022.

16 TEND Project (see 15).

17 Young, Stella. “I’m Not Your Inspiration, Thank You Very Much.” TEDxSydney, April 2014.