I know IT is critical to our business, but I really don’t have the time. Anyway, what have I got a CIO for? I just want to concentrate on my core business.

— CEO of a global energy company

While most business leaders would agree that having a digital strategy is of crucial importance today, many continue to see this as a technology issue, and as such, the responsibility of their IT function. This is the very same function that many of these chief officers have traditionally viewed as a cost center, questioning the extent to which technology has delivered on its promise. “Too expensive,” “not responsive,” “not innovative,” and “not flexible enough” are just some of the negative comments we regularly hear. Blame for this scenario has inevitably been placed at the door of the company’s CIO. After all, he (or she) is responsible for IT, right?1 Well, this was not exactly true in the past, and it is certainly not so in the digital era.

Our research and consulting reveal that CEOs and their CxO colleagues play a pivotal role in determining whether or not their organizations exploit the innovative opportunities provided by digital technologies. Creating and sustaining value from digital investments requires the CEO’s focused attention and oversight. CEOs set the tone, and their active participation determines whether their organizations optimize a return from any spending on IT. Most CEOs don’t seem to understand this or quite know what they should do.

Unlocking Value from Digital Initiatives

Senior business executives often feel very exposed when having any conversations to do with digital, as they don’t consider themselves technically literate. They can certainly be forgiven for being overwhelmed by the never-ending stream of new technologies and buzzwords that emanate from the IT industry. The usual and easiest response is to delegate — or, more often, abdicate — responsibility for anything digital to the CIO. This is a grave mistake.

Beyond buzzwords, what we are seeing is a seismic shift in the role of technology in organizations. Technology is more and more embedded in everything we do as we move into an increasingly hyper-connected digital world, a world in which technology is driving significant social, organizational, and industry change.

The value from digital rarely comes directly from the technology itself, but rather from the change that it both shapes and enables.2 It is this change — ranging from changes to the business model to an individual employee’s work practices — that increasingly represents by far the greatest and most difficult part of the effort required to realize value from digital investments. In short, what ultimately determines success is how well any required transformation is managed.

While digital technology delivers a capability — based on its ability to transform the way information is captured, processed, managed, and exploited — leveraging it requires the development of complementary business capabilities.3 For example, successfully deploying CRM software on time and on budget will deliver little unless sales, customer service, and fulfillment processes are redesigned; staff are trained to have the right conversations with customers; data quality improves; and marketers build the right competencies to use all the data that will now be available to them.

Labeling and managing such investments as “IT projects” and palming off accountability on the CIO is a root cause of the failure of so many of these efforts to generate the expected payoff. As they are investments in IT-enabled change, accountability for their success must rest with senior executives and line-of-business (LOB) management. Consequently, the role of the CIO shifts from a technology-centric, control-oriented supply role to a business-centric orchestrator, broker, and influencer role.

CEOs, in particular, must understand and embrace their essential role. Supported by the board and executive management team, they must acknowledge their accountability for creating and sustaining value in the digital world by ensuring that effective governance of IT-enabled business change is in place. This means governance that goes beyond the traditional notion of IT governance to strong business governance of IT. Governance that is about culture, mindsets, and behavior, not merely establishing structures, processes, and other instruments. Governance that is focused on value, with the realization of value — both expected and emerging — being actively managed throughout the lifecycle of investment decisions.

Navigating the Digital Landscape

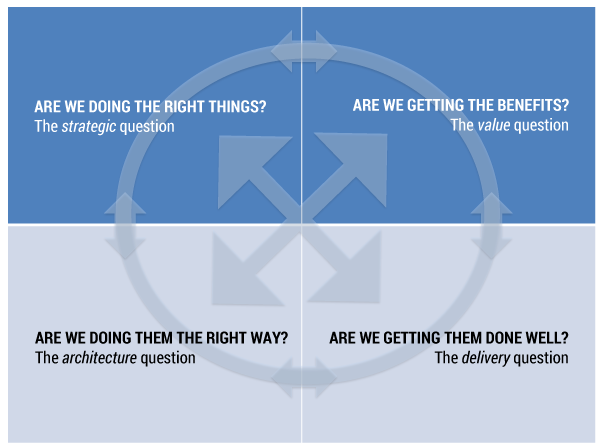

Working with business leaders, we have developed a simple yet powerful framework to help them navigate the digital landscape. It is based on four business-focused questions that are at the core of effective governance of digital and that every business leader should have in his or her head. We call these questions the four “ares” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 — The four “ares.”

Considering and answering the four “ares,” both individually and collectively, on an ongoing basis provides CEOs and executive management with the knowledge they need to orient and steer their organization’s digital journey and accompanying investments. It enables them to move beyond a culture of delivery (“build it and they will come”) to a culture of value, focused on creating and sustaining value from the organization’s IT spending from initial investment through to operation of the resulting assets.

“Are” #1 — Are We Doing the Right Things?

This is the strategic question. The first accountability of the CEO is to clearly and regularly communicate what constitutes value for the enterprise and the strategic intent to which all investments must contribute and against which their performance will be measured. To ensure that the capabilities of current or emerging technologies are considered in both shaping and enabling strategy, the CEO should sponsor and actively participate in regular forums where the CIO helps the leadership team understand the opportunities to create and sustain value enabled by the technologies and the changes required to take advantage of those opportunities.

Over a decade ago, when he took over the reins at global law firm Allen & Overy (A&O), David Morley recognized the disruptive potential of digital for his industry. This belief drove the firm’s strategic intent: “How we use technology and bring it to bear in our work will be an important differentiator for us,” Morley observed.4 With healthy growth and margins, the firm is consistently recognized as the most innovative law firm by the Financial Times in its annual ranking of global legal practices. The firm’s CIO is a key member of the leadership team, continually challenging his C-suite colleagues to explore how IT might improve the performance of lawyers in their daily work as well as how technology can disrupt what has been a very traditional industry, slow to embrace changes. Moreover, A&O has established an innovation board, with external membership, and sets aside a sizeable budget for experimentation and pilots in its quest to identify potentially game-changing IT innovations. This latter point has required the firm to become more accepting of failures.

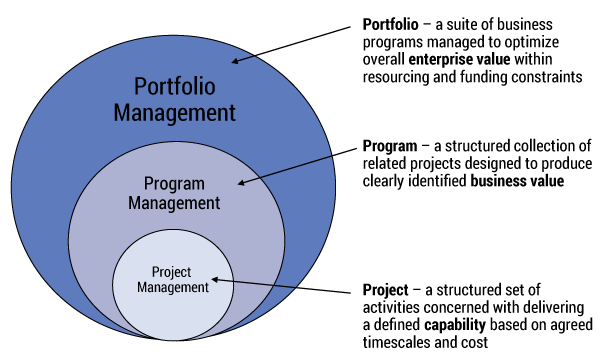

The second accountability is ensuring, through the initial investment selection process and regular portfolio reviews, that resources are allocated to investments that are both aligned with and have the greatest potential to contribute to the strategic objectives. (See Figure 2 for the distinctions between portfolio, program, and project.) This requires balancing both attractiveness and achievability in assessing the relative value of proposed investments. Investments can then be prioritized to maximize the value of the overall portfolio so that they provide optimal value, at an affordable cost, with a known and acceptable level of risk.

Figure 2 — Portfolio, programs, and projects. (Source: Thorp.)

Even in the case of a purely technological investment (e.g., to increase network capacity, mitigate risk, or reduce ongoing IT infrastructure costs), while the CIO is responsible for developing and presenting the business case, the CEO is ultimately accountable for ensuring that the decision to proceed is made based on contribution to business value — balancing benefits, cost, and risk.

“Are” #2 — Are We Doing Them the Right Way?

This is the architecture question. Because this question is usually thought of as relating to technical architecture, CEOs generally consider it a technology issue and thus the domain of the CIO. Nothing could be further from the truth. This is akin to going directly to a construction company without any architectural drawings. We advocate a broader view of architecture — an operating model — which has both organizational and technology components.

You would be unlikely to buy the components of a building — bricks, mortar, wood, doors, pipes, and so on — and assemble them without first having a blueprint of what the finished structure will look like and a plan for how all the components fit together. This blueprint would be defined by a clear view of the purpose of the building and how it is going to be used. All construction work would be carried out referring to this blueprint. Any possible changes to the building or potential alternative uses would be framed by architectural choices.

In a similar way, enterprise architecture is about the fundamental design of the components of the business system, the relationships between them, and how they support the delivery of the organization’s business model. Architectural choices shape the operating model, reflecting how the organization should “work” in executing strategies and its need for agility in responding to changes in the competitive environment.

At one healthcare group,5 a newly appointed CEO found that, strategically, they were doing many of the right things, but they were doing many of them in the wrong way. For example, in implementing a picture archiving and communication system for radiology, individual hospitals had previously been allowed to follow their own processes when deploying the technology. This resulted in different configurations of the same software to accommodate the different ways of working in many of the 15 hospitals in the group, and different vendors being selected in others. Today, all of the group’s investments must adhere to an architectural map that emphasizes process standardization. This map also mandates the places where information integration is needed.

The CEO is accountable for seeing that there is an overall enterprise architecture. LOB managers and the CIO are accountable for ensuring that existing and new business and technology capabilities are consistent with this architecture, and that any exceptions are the result of informed management decisions based on a clear understanding of the strategic implications and business risks associated with them.

“Are” #3 — Are We Getting Them Done Well?

This is the delivery question. Although there is a significant body of knowledge on delivery, it is the one area where the failure of governance continues to result in significant and very visible failures. John Doyle, the former auditor general of British Columbia, Canada, has posed the question: “Why is it that every major transformation initiative always ends up being managed as an IT project?”6 The answer is simple: delivery is thought of as being limited to deployment of the enabling technology and, again, is left to the CIO. As in the case of architecture, delivery has both business and technology components — and the business components have increasingly become the more significant and more complex of the two.

All too often, a lack of rigor at the outset leads to a lack of clarity around the desired outcomes and a failure to understand the full extent of business change required to realize those outcomes beyond the new IT capability. The consequence is that what might start out as a business investment very soon ends up being managed as a technology initiative. The “IT project” then encounters significant scope creep and degenerates into an unplanned and complex mix of technology and business change, unexpectedly impacting staff already hard pressed to do their day jobs and ill prepared to take on the additional work required to bring about the necessary changes.

To ensure that things are done well, one large US manufacturer7 develops benefit maps (for doing the right things) to understand the full scope of organization change required and uses the maps to derive clear accountabilities for the change, which are assigned to named managers. These maps link up business drivers with the investment objectives and expected benefits with a very clear elaboration as to the required business changes to achieve benefits. They also specify both leading indicators (to get early warning of when things might be going off track before they actually do) and lagging indicators (for end outcomes).

However, no matter how rigorous the up-front analysis, things will change as work moves forward, and there will be unexpected, and sometime unpredictable, surprises. We cannot — as has too often been the case in the past — move blindly ahead to the predefined solution, not being open to any questioning of the expected outcome or approach and focusing solely on controlling cost and schedule. To use a sports analogy, we must not focus more on the scoreboard than on the plays that are necessary to get on the board.

To ensure that things are getting done well, the executive team member or LOB manager who is the designated business sponsor of an investment is accountable for:

- Planning, resourcing, and executing the necessary organizational and technical projects that make up the program of change (although planning, resourcing, and executing the necessary technical projects would be delegated to the CIO)

- Monitoring the overall performance of the program and reporting progress to the executive team, including issues and actions taken or required (which could include changing the program plan or terminating the program)

- Updating the business case as changes occur

“Are” #4 — Are We Getting the Benefits?

This is the value question. Surprisingly, this is the question that receives the least attention in most enterprises: few measure or assess whether expected benefits have been delivered. As in the case of the strategic question, this question cannot be delegated to the CIO — although, all too often, it is. IT contributes to business value from one of three sources:

- Automation — where the deployment of IT in business processes speeds up transaction processing, enabling cost reduction and generally “decluttering” processes.

- Augmentation of human cognitive processes — by providing broader and timelier access to higher-quality information. Value here comes from how people use this information, such as data analytics leading to new insights and more informed decision making (e.g., optimizing inventory holdings to reduce working capital, optimizing delivery routes to improve delivery times, predicting customer behavior).

- Business transformation — where current, new, or emerging technologies provide opportunities for management to rethink and reshape their business and business models or, in some cases, their industry.

To ensure that expected benefits are realized and changes are sustained from digital transformation:

- The CEO is accountable for maximizing value from the portfolio of business change investments.

- The CEO and LOB managers are accountable for the quality of business cases and making sure that they are being updated and used as a management tool throughout the lifecycle of an investment.

- The CEO, LOB managers, and the CIO are responsible for regularly reviewing the performance of investments, which may result in their adjustment or termination.

- LOB managers are accountable for ensuring that business units (BUs) are using new or improved assets — including new or changed business services, IT services, and information — in an appropriate manner such that benefits are realized and sustained.

- LOB managers and the CIO are accountable for ensuring that there is relevant and timely information to monitor the realization of outcomes (lagging metrics) and the expected contribution from the changed capabilities (leading metrics) so that the organization can get an early indication of when things are not going as expected and take timely corrective action.

Figure 3 provides more detailed questions behind each of the four “ares” that business leaders should be continually asking. Addressing the four “ares” is not just something to be done once to secure funding for a proposed investment, nor can these questions be addressed in a sequential, or waterfall, way. They must all be considered, both individually and collectively, on an ongoing basis to ensure that value is realized.

Figure 3 — Key questions related to the four “ares.”

While much of this article discusses the initial investment in and implementation of a program/project, most of the benefits are realized (or not) and costs are incurred only after the new IT system goes live. Once IT assets move into operational mode, the focus is largely on efficient, reliable, and secure operation, and all too often scant attention is paid to their contribution to business value. The four “ares” should be applied over the full lifecycle of an investment decision — beyond the initial investment to the new or improved assets (e.g., information, processes, IT services) that result from it.

Clarifying the Role of the CEO and Leadership Team in Digital Transformation

Governance is about what decisions need to be made, who gets to make them, how they are made, and the supporting management processes, structures, information, and tools to ensure that decisions are effectively implemented, complied with, and achieving the desired levels of performance. This requires that the accountabilities and responsibilities be well understood and clearly and unambiguously assigned, the reward system be aligned, and relevant performance metrics be in place.

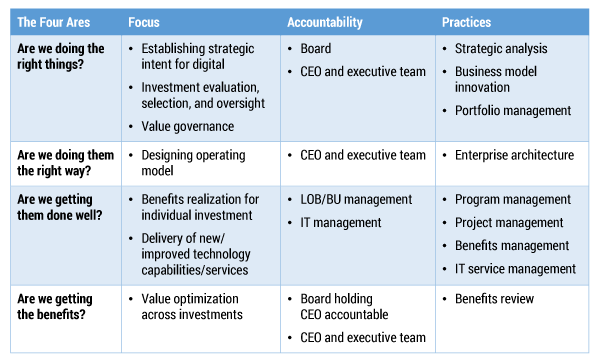

Table 1 summarizes the primary areas of focus for each of the four “ares,” indicating where accountabilities lie and highlighting proven processes and practices to support effective governance. The key elements include:

- Articulating a clear strategic intent for digital

- Managing digital transformation investments as a portfolio of business change programs

- Developing comprehensive and consistent business cases describing: the expected outcomes; ownership of, and accountability for, the outcomes; the full scope of the changes required to achieve the outcomes and accountabilities for making sure those changes happen; the expected contribution of each change to the outcome(s); risks to the achievement of outcomes; and metrics

- Objective evaluation criteria enabling prioritization and selection of investments

- Inclusive and ongoing engagement of all the stakeholders affected by the change

- Ongoing management of the journey, including:

- Use of the updated business case as the key management tool

- A strong gating process for progressive commitment of resources to ensure that, when things are not going to plan, timely corrective action can be taken, including changing course, revisiting/changing the outcomes, or cancelling the program

- Capturing, reviewing, and acting upon lessons learned so that mistakes are not repeated and value continues to be maximized

Table 1 — Focus, accountability, and practices across the four “ares.”

CEOs and their leadership teams often balk when we present this list to them. Yet CEOs need to recognize that IT is increasingly embedded in all aspects of their business and falls within their realm of responsibilities. This doesn’t mean that CEOs need to have a detailed knowledge of technology, any more than they need to be experts in HR or construction, but they do need to know enough to guide and direct their organization’s investments in IT-enabled change such that they create and sustain business value. Nor should this be seen as creating a large, time-consuming bureaucracy in a world where the need for agility has never been greater. Rigor here is not measured by the weight of documentation, or the time taken to develop it, but by the quality of the thought processes, the conversations, and the decisions made.

We are not suggesting the CEO take a hands-on approach to all IT investments — that is just not possible. However, CEOs do need to be confident that proper governance is in place across the organization to ensure that appropriate rigor is applied to governance choices and their outcomes, and that compliance with and the effectiveness of the governance are regularly audited, reported on, and improved where necessary.

The member of the executive team or LOB manager assigned the role of business sponsor for a particular program has overall responsibility for the realization of benefits. LOB and IT management each have accountability for delivering the required business and technology capabilities from business and technology projects constituting the program. Program management requires joint engagement between business and IT management, while project management is not the sole responsibility of IT management, as LOB managers also have business change projects to manage.

From Common Sense to Common Practice: The Digital Leadership Agenda

A common reaction to the four “ares” is that they are just common sense. Indeed they are; unfortunately, they are not common practice! This is certainly not for lack of guidance — a wide range of frameworks, methodologies, practices, techniques, and tools for governance, portfolio management, benefits realization, and change management have become available over the decades. However, if leadership teams are to move beyond words in addressing the challenge of creating and sustaining value from increasingly disruptive investments in digitally enabled change, emphasis must be placed on action — on engagement and involvement at every level of the enterprise. Enterprises all too often run into the knowing-doing gap: they know what needs to be done (or at least the knowledge is widely available), but they just don’t do it. The choice for leadership here is simple: lead the digital transformation or stand back and watch your organization become irrelevant.

We have found that organizations that consistently leverage digital technologies share all or many of the following characteristics:

- A strong digitally literate executive leadership team with commitment to both communicating strategy and embedding a value culture — a team that:

- Recognizes that technology is increasingly embedded in, and an integral part of, their business

- Ensures that the complementary business changes required to ensure that value is created and sustained from the use of that technology are understood, communicated, and effectively managed

- A highly informed middle management structure used to help coach and embed value-focused practices into the enterprise

- Clearly defined structure, roles, and accountabilities for all stakeholders related to creating and sustaining value from digital transformation

- A rigorous front-end planning process, with intense scrutiny applied to business cases at selection and reapplied throughout their lifecycle

- A portfolio management approach in which investments are selected based on balancing desirability and achievability of operational and strategic contribution

- A long-term commitment to dedicated, trained, and informed human resources to promote, support, and continuously improve the value management processes and practices

- A culture that embraces the potential of data and is not afraid of experimentation

- A value-based reward system for teams and individuals at all levels within the enterprise

There Is a Better Way

Technology continues to be something that many business leaders are only too happy to abdicate to their CIO. This must change. Digital is a team effort. Business leaders, starting with the board and the C-suite, must become digitally literate, recognize and accept their accountability for creating and sustaining value from investments in digitally enabled business change, and drive that accountability down through their organization.

Every journey starts with the first step. The journey we are advocating will not be easy for many, but unless business leadership takes that first step, value from business change investments involving IT will remain elusive, and the promise of the digital economy will not be realized. If organizations are to survive, let alone thrive, in the rapidly evolving digital economy, the status quo is not an option.

1 One worrying finding from our research is that in many organizations, there is significant ambiguity around the CIO role. Executives at all levels are unsure as to what a CIO is and what to expect of their CIOs: 64% of the CIOs we surveyed revealed that their conception of what the role involves differs significantly from that of their CEO and CxO colleagues, with these diverse views ultimately shaping (sometimes contradictory) expectations for the role.

2 For empirical evidence, see “Performance Impacts of Information Technology: Is Actual Usage the Missing Link?”

3 See “The Transforming Power of Complementary Assets” and “Managing the Realisation of Business Benefits from IT Investments.”

4 For more details about the A&O digital journey, see the case study “IT Innovation at Law Firm Allen & Overy,” available from Joe Peppard.

5 This example is based on a consulting assignment.

6 Interview with John Thorp.

7 This example is based on a consulting assignment.