Contributors: Devin Diran, Francesca Ciulli, and Albert Meijer

AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 10

The importance of linking the green and digital transitions is undisputed. However, while both will transform our societies and economies, they are very different in nature and dynamics. This requires understanding the “twin transition” as a new phenomenon.

The European Commission has shown clear strategic direction and ambitious leadership by acknowledging that these two trends will shape Europe and its future. But the simultaneous pursuit of digital and green transitions raises questions for industry and government institutions alike. How can we steer the twin transition in the desired direction while avoiding recognized risks? How can we ensure that digital and green initiatives support and enhance each other rather than working against one another? What policies can simultaneously promote digital innovation and environmental sustainability?

One thing is certain: a just transition is crucial for widespread acceptance of green-digital solutions.1 Ensuring that the twin transition proceeds in a fair, equitable manner hinges on a holistic understanding of its dynamics, including opportunities, pitfalls, and remaining uncertainties.

In this article, we propose four priority areas that managers and policymakers should consider as they work to understand and advance the twin transition. Our ideas are based on a joint session with researchers, policymakers, and practitioners at the first annual symposium of the Special Interest Group on Digitalization and AI for Sustainability (DAISY), hosted by the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

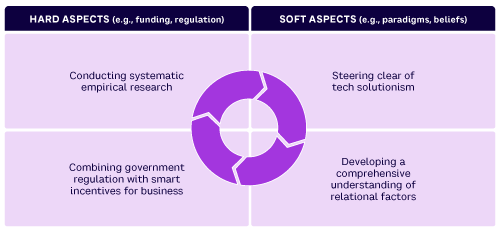

During the session, we had a unique opportunity to explore the interplay between the green and digital transitions, discuss drivers and concerns, and gather expert advice on how it may be possible to align the transitions. Based on this, we identified four priority areas for better understanding and advancing the twin transition (see Figure 1):

-

Conducting systematic empirical research to inform data standardization efforts and overcome the problems associated with data fragmentation (e.g., operational inefficiencies and security risks)

-

Steering clear of “tech solutionism” and exploring areas where little or no technology use can be beneficial

-

Developing a comprehensive understanding of the relational factors at play in the twin transition (e.g., power imbalances, fairness)

-

Combining government regulation with smart incentives for business in a well-rounded twin transition policy

These four areas are in line with the EU’s call for a proactive and integrated management of social, technological, environmental, economic, and political domains in twin transition.2 We believe the connections between “hard” and “soft” aspects, such as funding research on new technologies while considering alternatives to tech solutionism and fostering social innovation, are especially important. By combining hard and soft aspects, managers and policymakers (as well as researchers and civil society) can champion a comprehensive, multidimensional approach that leverages the strengths of various stakeholders and helps the twin transition proceed in a fair and equitable way.

The Intricacies of the Twin Transition

“We should harness this transformative power of the twin digital and climate transition to strengthen our own industrial base and innovation potential,” announced European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen at the advent of the European Green Deal.3

It is undisputed that the digital transformation has the potential to be a powerful tool in the fight against climate change and the move toward a more sustainable future. In fact, in an era where we are transgressing planetary boundaries, achieving climate goals is virtually impossible without digital technology.4,5 Still, even though policymakers talk about a win-win and express confidence in their ability to govern and control the development of the twin transition, there are problems.6

The green and digital transitions can reinforce each other in many areas, but they do not necessarily align. Digital technology deployment can have unintended consequences, including rebound effects nullifying net emission reduction achieved or concerns about social aspects like data security and privacy.7 The fact that it’s impossible to fully forecast these effects and the difficulty in ensuring collaboration between the many sectors involved in managing these effects poses an enormous challenge for governing the twin transition.

The academic debate on unintended consequences and the crossover of multiple transitions is just beginning, and problems are already popping up in practice. What infrastructure investments should be made to support the twin transition? Which digital technologies are most critical for achieving sustainability objectives? How should we allocate funding? “There is no time to waste,” states a recent report by the European Commission.8 Indeed, the twin transition is already taking place and requires decisions.

Conducting Systematic Empirical Research

To make informed decisions, managers and policymakers need a reliable evidence base. Empirical research is crucial for identifying replicable best practices and uncovering potential risks (e.g., job displacement and digital divides). Unfortunately, current research often overlooks the negative social, economic, and environmental impacts of the twin transition and lacks empirical data.9 When numbers and figures are available (e.g., measured carbon emissions), they tend to be difficult to compare and translate into data-driven insights designed to guide policymakers and businesses.

We need large-scale projects that allow for consensus building on definitions, standards, and which data to collect and share. A good example is CIRPASS, a collaborative initiative funded by the European Commission to prepare for the gradual piloting and deployment of a standards-based Digital Product Passport (DPP).10 Consisting of 31 partners in 15 countries, CIRPASS aims to build stakeholder consensus on key data for circularity, define vocabulary standards to be included in the DPP, develop a cross-sectoral product data model, and propose an open DPP data-exchange protocol.

Researchers must leverage insights from such projects to create use cases and evidence-based roadmaps for the twin transition in different sectors. New approaches, such as the decentralized data reuse proposed by the Open Science in Qualitative Management Research (OPEN-QUAL) initiative, can help researchers compare qualitative case studies and datasets for a better understanding of the dynamics of the twin transition.11

Managers and policymakers can take a leading role in supporting and funding research initiatives that deliver the type of empirical, reliable, and comparable data essential for monitoring the progress and success of the twin transition over time.

Steering Clear of Tech Solutionism

Twin transition policy discussions tend to portray technology as a solution to environmental challenges, with less emphasis on how technology can contribute to the problem. This could lead to technology becoming a pacifier that prevents us from tackling the structural causes of sustainability problems. For instance, it is often presumed that as net zero technologies become widely available (e.g., clean energy for air travel, net zero data centers), our consumption patterns can continue as usual. Instead, technology should contribute to deep sustainability transformations.12

Government support for clean air travel in the Netherlands is an example of the reliance on technology as a solution.13 The country’s goal is to reduce CO2 emissions by 35% by 2030 thanks to the development of “clean” airplanes and sustainable fuels. However, the number of flights is set to increase by 40% and the number of passengers by 60%.14

Relying on new technologies for sustainable air travel is an appealing promise for airlines, travel agencies, and consumers as they offer a way to maintain air travel without drastic cuts, but there is a real risk that these technologies will not be developed fast enough and will reinforce the belief that fundamental changes to the way we use air travel are not required.

Excessive reliance on digital technologies as a solution for sustainability can hinder essential structural changes. We call on managers and policymakers to discuss and investigate whether technology is the best solution to a given sustainability problem, whether low-tech solutions can be employed, and whether nonuse of technology can contribute to developing a better solution. We must let go of the idea that if we are not using the latest technology, the solution is old-fashioned.

Additionally, we call on researchers to support decision makers with evidence about circumstances in which low-tech solutions or technology nonuse create better outcomes.

Developing a Comprehensive Understanding of Relational Factors

The twin transition requires the coordinated efforts of a wide range of stakeholders, including governments, businesses, civil society, and international organizations. It is often assumed that these stakeholders will collaborate for the sake of sustainability and that solutions that are technically possible will be implemented. This assumption is problematic because relevant stakeholders lack connection, trust, and shared values, leading to power imbalances.

Take food-waste-recovery platforms like Too Good To Go, Olio, and MyFoody. These platforms, designed to transform traditional supply chains into circular ones, have emerged to address issues such as the lack of connection between relevant stakeholders. By leveraging digital technologies, these circularity brokers connect previously disconnected actors and facilitate their interaction.15

The underlying technology is rather simple, but these platforms face challenges related to relational factors. For instance, using digital platforms increases visibility, but this may worry suppliers who prefer not to disclose the amount of waste they produce. Some managers of donating firms are uncertain about legal risks and potential damage to their business reputation. There are also concerns around data sharing and which firm gets to be customer-facing.

It is essential to anticipate these issues and conduct a power analysis up front.16 What is being proposed? Who gains from it? Who is potentially harmed or marginalized? Ignoring these relational factors jeopardizes the success of promising technological solutions.

Combining Regulation with Smart Incentives

A successful twin transition requires coordinated efforts from a variety of stakeholders, with businesses and industries playing a key role. An effective policy must strike a balance between regulation and incentives to drive business action. Relying only on regulatory pressure is not sufficient to motivate the private sector to take ambitious steps and can result in digital greenwashing. Moreover, policies in the digital domain are often perceived as vague, reactive, and lagging.

We urge policymakers to expand the use of smart incentives for businesses and citizen initiatives, alongside regulation, to stimulate private sector engagement and deliver win-win outcomes. This balance between regulation and smart incentives represents a measured approach, one that acknowledges the potential of technology solutionism to address societal challenges while recognizing there may be unintended consequences.

Policymakers should also develop a clear vision of both the desired and undesired roles and impacts of digital technologies in the short and long term, using a participatory and inclusive approach that involves all sectors of society. Explorative scenario analysis is a valuable tool for gathering this knowledge.

A notable example of this type of effort is the National Coalition for Sustainable Digitalization in the Netherlands, which engages in agenda-setting for policymakers from an industry perspective. Although the initiative still lacks crucial input from citizens, it serves as a building block toward a balanced approach to regulation and incentives.

Another prime example is the French government, which has been at the forefront of integrating ecological considerations into IT while balancing regulation and incentives.17 Key legislation includes the 2020 Anti-Waste and Circular Economy Law (AGEC) and the 2021 Reducing the Environmental Footprint of the Digital Sector (REEN) Law. AGEC aims to inform consumers about the environmental impact of their digital consumption, and REEN focuses on increasing awareness, promoting reuse and recycling, implementing sustainable digital practices, and supporting energy-efficient data centers. Both incentivize companies to reduce the ecological footprint of digital technologies.

Moving Forward

To successfully navigate the twin transition, a holistic approach is essential: one that recognizes the complexity of both technological and societal transformations. As the transition progresses, it will require a robust, multidimensional strategy that integrates technological innovation with sustainability principles, ensuring that the environmental and social dimensions are equally prioritized.

Among the most critical elements in understanding and advancing the twin transition lies in addressing both its hard and soft aspects. On the one hand, governments and industries need to continue investing in technologies, infrastructures, and regulatory frameworks: the “hard” elements. On the other hand, there is a growing need to challenge established paradigms, rethink consumption patterns, and engage in transparent and inclusive social dialogues: the “soft” factors that will underpin the cultural and behavioral shifts required for a just transition.

The four priority areas can be categorized into needs and opportunities based on their urgency and potential to unlock new advancements.

“Conducting systematic empirical research” and a “comprehensive understanding of relational factors” are needs; these are essential areas that must be addressed to ensure the success and smooth governance of the twin transition. Without these, the transition could stall or cause unintended harm.

“Steering clear of tech solutionism” and “combining government regulation with smart incentives” are opportunities; these are areas that present potential for innovation, better practices, and a deeper alignment between green and digital transitions.

By devising actions from the four priorities (see Figure 2), policymakers, the business community, researchers, and civil society can ensure the twin transition proceeds in a fair, inclusive, sustainable way. Ultimately, the success of the twin transition will depend not just on technological advances, but on a shared commitment to rethink societal norms, challenge entrenched power structures, and foster more equitable economic and social development models.

Going forward, continuous reflection and adaptability will be crucial. We must remain open to questioning the directionality and efficacy of digital solutions, especially when low-tech alternatives offer more sustainable and equitable paths.18 The digital and green transitions should not only coexist, they should actively reinforce one another, creating a future where technological progress and environmental sustainability are mutually supportive. Meanwhile, the research and practitioner community must further expand the debate on what constitutes a deep sustainability transition and a deep digital transition.19,20

References

1 Muench, Stefan, et al. “Towards a Green & Digital Future: Key Requirements for Successful Twin Transitions in the European Union.” Joint Research Centre, European Commission, 2022.

2 Muench et al. (see 1).

3 “Speech by President-Elect von der Leyen in the European Parliament Plenary on the Occasion of the Presentation of Her College of Commissioners and Their Programme.” European Commission, 26 November 2019.

4 “Tech Must Help Combat Climate Change, Says Sundar Pichai.” The Economist, 17 November 2020.

5 Falcke, Lukas, et al. “Digital Sustainability Strategies: Digitally Enabled and Digital-First Innovation for Net Zero.” Academy of Management Perspectives, 18 March 2024.

6 Kovacic, Zora, et al. “The Twin Green and Digital Transition: High-Level Policy or Science Fiction?” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 17 June 2024.

7 Bohnsack, René, Christina M. Bidmon, and Jonatan Pinkse. “Sustainability in the Digital Age: Intended and Unintended Consequences of Digital Technologies for Sustainable Development.” Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 31, No. 2, December 2021.

8 Muench et al. (see 1).

9 Piscicelli, Laura. “The Sustainability Impact of a Digital Circular Economy.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, Vol. 61, April 2023.

10 CIRPASS website, 2024.

11 “Innovating Methods for Open Science in Qualitative Management Research (OPEN-QUAL).” Dutch Research Council (NWO), accessed October 2024.

12 Lange, Steffen, et al. Digital Reset: Redirecting Technologies for the Deep Sustainability Transformation. Oekom, 2023.

13 Meijer, Albert. “Perspectives on the Twin Transition: Instrumental and Institutional Linkages Between the Digital and Sustainability Transitions.” Information Polity, Vol. 29, No. 1, February 2024.

14 “Aviation Industry Wants to Reduce CO2 Emissions by a Third.” De Ingenieur, 4 October 2018.

15 Ciulli, Francesca, Ans Kolk, and Siri Boe-Lillegraven. “Circularity Brokers: Digital Platform Organizations and Waste Recovery in Food Supply Chains.” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 167, April 2019.

16 Avelino, Flor. “The Paradox of Power in Just Sustainability Transitions.” Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, 2024.

17 “Green IT.” French Government, 12 January 2024.

18 Pel, Bonno. “Is ‘Digital Transition’ a Syntax Error? Purpose, Emergence and Directionality in a Contemporary Governance Discourse.” Journal of Responsible Innovation, Vol. 11, No. 1, August 2024.

19 Schot, Johan, and Laur Kanger. “Deep Transitions: Emergence, Acceleration, Stabilization and Directionality.” Research Policy, Vol. 47, No. 6, July 2018.

20 Pel (see 18).