AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 12

Financial acumen is as crucial as ever in the digital era, as it can quickly reveal which enterprises are, in reality, just technologies in search of a sustainable business model. Likewise, such knowledge can help leaders discern early warning signals (e.g., declining margins, productivity slides, customer churn, and inventory bloat) that a faltering business needs IT modernization. Yet the mere mention of financial statements usually generates scorn about arcane accounting terminology, puzzled looks at endless spreadsheet grids, and eagerness to move on to more “comfortable” topics.

Nonetheless, just as routine medical checkups and fundamental health knowledge are important to wellness, all managers must periodically review and understand their organization’s overall financial well-being. Just as metabolic blood test reports provide health indicators, financial statements reflect business vitality. Importantly, reported data, whether medical or financial, holds no answers, but it begs users to ask the right diagnostic questions — especially if something has gone awry.

The digital era does not change that. Despite the fluid lexicon of business buzzwords, leaders of well-run enterprises understand fiscal responsibility, deliver competitive returns, and communicate with clarity and candor. Detailed below are five timely and timeless insights about financial performance that ensure stewardship, especially in times of rapid technology-driven change (see the Appendix for terminology).

Insight 1: Companies Live by Earnings But Perish by the Balance Sheet

The business press and financial markets repeat the mantra of “earnings, earnings, and earnings.” What is often overlooked, to great peril, is management’s first and fundamental fiduciary responsibility of stewardship. Established in the era of sea merchants, the first accounting methods reconciled resources entrusted to a crew upon departure against the treasure accumulated by journey’s end. Today, reports of companies’ demise often do not discuss lack of profitability; rather, they point to an inability to meet financial obligations. Successful leaders prioritize stewardship over empire building.

Consider four homes on a residential block, all of similar size and value. The assets appear the same, but a financial “X-ray” of each could reveal very different stories. House #1 was purchased 25 years ago at a much lower price than it would sell for today, and it has just a few years left on its mortgage. The owners of House #2 purchased the home this year, having scraped together a 20% down payment, and have decades of payments ahead. The family in House #3 paid cash and have no concerns about looming mortgage payments. House #4 is occupied by owners with hefty credit card debt who are in immediate jeopardy of foreclosure. By analogy, four corporate competitors may have similar assets and annual income, but very different pressures and flexibility due to obligations.

Countless businesspeople, athletes, and actors have earned fortunes and then filed for bankruptcy. We may have seen their earnings, but never their balance sheets. When examining a balance sheet, in either absolute monetary units (i.e., dollars, euros, etc.) or relative terms (i.e., percentage of total assets), the three most important indicators to identify are (1) growth (2) mix, and (3) the largest item.

Company finances, like our retirement accounts, are usually either expanding or contracting; they rarely stay the same. A cursory examination of balance sheets over time will reveal, in money or percentages, changes in individual account or (sub)total lines. Knowing these changes provides an informed perspective on whether the workforce is being asked to do “more with less” or “more with more.”

Growth can be desirable, but if unstable, it can be dangerous. Mix, the second critical balance indicator, provides appropriate context. Shoppers in grocery stores can often be observed closely studying product ingredients. What constitutes a food product or a company balance sheet reveals much about each’s worthiness. For instance, a primary ingredient in many cereals is sugar while plain oatmeal contains just one ingredient: oats. A cake made for four or 400 has the same relative mix of eggs, butter, sugar, and chocolate, but the needed quantities will be vastly different.

On its “ingredients” list, the balance sheet shows assets, not by size, but in descending order of liquidity: how readily they can be turned into cash (hence, cash and cash equivalents are always first). Once capitalized (i.e., recorded on the balance sheet), an asset remains until it is sold, is exchanged, is depleted, is impaired, becomes obsolete, or is used to settle a liability.

For companies, the balance-sheet mix reveals the degree to which holdings consist of cash, accounts receivable (customer IOUs), inventory, property, intangibles (e.g., patents, or other investments) and how such resources have been financed (via short- or long-term debt or equity infusion from owners). A consistent mix, especially with growth, over time demonstrates stability and disciplined management (or lack thereof).

No examination of the mix on the balance sheet is complete without identification of the largest item(s) reported as assets or financing vehicles. For a retailer, it might be inventory or stores, depending whether they are owned or rented. For a movie studio or pharmaceutical firm, the largest asset can be intangible (film or patent rights, respectively).

The risks and pressures facing organizations and managers vary greatly depending on asset and debt mix. Assets require varied expertise, insurance, technologies, and other attention to manage. The largest financing item might be accounts payable (supplier bills due soon), bank loans, or retiree obligations; each has its own time horizon and implications. For instance, large aerospace companies, such as Boeing or Airbus, often receive customer payments in advance to fund the building of airplanes and spacecraft.

Such attention to the balance sheet is the foundation of a well-run enterprise and the essence of management obligation (as stewards) to first do no harm. Consistent profitability follows an understanding of the company’s balance sheet and disciplined management of key resources.

Insight 2: Know the Company Speed Limit

What is a company’s most important metric? Such a question is as debatable and unanswerable as the singular most important health measure. Complex systems require multiple measures across vital components, and, as such, critical universal measures exist.

One key indicator is company sales growth rate percentage. Sales revenue is, over time, the best quantifiable and verifiable evidence of strategy execution. Revenues quantify customers’ total purchases of a company’s products and/or services and are the essence of basic economics, the prices and quantities not only desired, but transacted.

If company sales revenue increased from US $100 million to $110 million in one year, its annual growth rate was 10%. The sales growth rate is analogous to a roadway speed limit, a benchmarking context by which all other changes can be interpreted. Is a company growing too fast, too soon? It depends. Is it safe to drive a car at 50 miles per hour? Many people impulsively nod yes, but the answer is situational. Such speed would be dangerous in a driveway or parking lot, out of compliance in a school zone, and potentially traffic-clogging on an expressway.

Managers need to know their employer’s sales growth rate in the past, present, and future to enhance decision and analysis credibility. For a company with an actual or anticipated sales growth rate of 10%, taming expense increases to a lesser rate results in profit growth, even while spending more.

The lesson is that cost cutting is different than cost control. Imagine two cars driving a great distance on an expressway, one car (sales) is proceeding at 70 miles per hour. Controlling the acceleration of the other vehicle (cost) to rate less than 70 mph increases the distance between the cars in each mile (in business terms, profit.) Both cars are still moving forward, but the rate of change is different, increasing the gap.

Retailers and restaurants can apparently increase total sales by opening locations. However, the growth of investment in storefronts, fixtures, and inventory may exceed the increase in sales, diluting the company’s overall performance and asset utilization. Perhaps online sales and delivery would work better. Similarly, distributors may increase sales in the short term by loosening customer credit requirements. Such sales growth may be problematic and costly if less creditworthy customers result in more rapid accounts receivable growth and eventual collection issues. Clearly, there is great value in knowing and using sales growth rate as a marker for sound business judgment.

Insight 3: Power of the Penny

Despite the old adage “a penny saved is a penny earned,” people often walk past pennies in parking lots, cafeterias, and just about every other place. We might think bending down to pick up a penny won’t change our lives, but the consequences are severe to our employers. For every million dollars of sales, 10% of the top line equals $100,000, and 1% equals $10,000 dollars. For large companies, for every billion dollars of sales, 1% equals 10 million dollars. One tenth of 1%, a sliver of copper, equals 1 million dollars to such a firm.

If the CFO of a $1 billion company learned of a consulting idea that would improve the business by “just” one tenth of 1% ($1 million), that executive would certainly know the value and consider paying a tidy sum for such guidance. On a smaller scale, an entrepreneur running a $5 million company can improve profits (and owner pay) by $50,000 with “just” a 1% improvement.

Leaders make numbers meaningful with clarity and simplicity. Doing so guides the workforce to understand why their jobs are important and recognize the big differences that small changes can make. Surprisingly, an extra penny can pay for a lot at most companies.

The penny concept also reinforces how hard it is to succeed in business. Even healthy, well-known businesses are challenged to generate 10% profits on sales. Stated in terms of time, 10% of the year is just over 36 days. Divide a company’s sales by 365. You will find that a tenth of a penny equates to about a third of a day, or approximately eight hours!

Relating time to money helps us look at things in a different way. Consider the value of each hour of work time. Think about what a meeting really costs, considering the approximate hourly rate of each attendee. Was the meeting time and money well spent? Would generative AI raise better questions and agentic AI more swiftly execute solutions?

The next time you see a penny on the ground, pick it up, and the next time you see a corporate penny hidden in plain view, guard that treasure — it is worth more than most of your colleagues ever considered.

Insight 4: Ratios Provide Perspective

Countless technical volumes are filled with encyclopedic lists of financial-statement ratios calculated by dividing a number into another, but the meaning of most ratios often gets lost. An easy way to assess the value of any key performance indicator is to ask the simple question, “What’s in the denominator?”

The denominator provides the context to scale the numerator. For example, sales revenue alone is meaningful, but divided by denominators, new insights emerge. Sales per employee, store, customer, transaction, hour, square footage, or assets yield different perspectives and actionable items that can improve the output (the numerator) by managing the denominator.

For example, “full service” movie theaters in recent years (pre-pandemic) moved from relying on occupancy (seats sold) to sales per seat, with dining as a new strategic offering. Innovators in technologies and medicine monitor the percentage of sales released in the last year, as new offerings often provide the highest price points and margins.

Focusing on the denominator creates perspective for comparing across time, companies, or industries. For example, managers can see liquidity reflected in the popular current ratio (current assets over current liabilities). Doing so illustrates how much of a company’s most liquid asset is soon committed to short-term obligations.

Such a calculation is similar to determining the level of comfort by comparing the balance in one’s checking and savings accounts to pending bills. There is no singular ratio that tells everything about a company, but using a workable set of meaningful indicators spotlights certain financial statement items for more attentive management.

Notably, the improvement or decline in ratio really depends on the difference in the growth rates of the selected numerator and denominators. Those differentials are even more meaningful when considering relative to the sales growth rate, discussed above.

Insight 5: Cash Flow Holds No Secrets

Cash flow is the lifeblood of an organization. Households, nonprofits, and publicly held companies all share one thing: over time, more cash must be received than is spent. Without sufficient cash to pay bills and no way to gain access to such cash, a company will quickly find itself out of business.

Accrual accounting, the most widely accepted corporate approach, matches revenues and expenses to time of transactions rather than when cash is exchanged (i.e. payment is often made in the month following service). Regardless of accounting methods, terminology, and timing, over time, cash flow reveals all about a company, just as review of the past few months of one’s debit or credit card statements will tell much about life.

Cash flow statements categorize the exchange of cash into three distinct activity sets: operating, investing, and financing. Operating cash flows are associated with a firm’s primary business activity. Net income differs from cash flows from operating activities, because the income statement recognizes revenues and expenses when earned or incurred, not when collected or paid.

Investing cash flows are related to the purchase and sale of a company’s non-current assets. When a company buys equipment to support its operations for one fiscal year, the cash spent is an investment in the future of the business. When the equipment is sold, the cash from the sale is considered investment cash inflows. Investments in financial securities (stocks and bonds) naturally fall into this category.

Financing cash flows are reported when companies raise or retire capital from creditors or shareholders. The receipt of cash from a bank loan or stock sales to owners are cash inflows. Conversely, dividend cash payments to shareholders or principal payments on loans are cash outflows.

Over time, successful businesses develop a pattern of generating sufficient cash from operations to purchase new assets, without continually requiring money from banks or owners. And what applies at the aggregate is certainly relevant at the project level, highlighting all managers’ responsibility to recognize that truly great business opportunities demonstrate positive cash flow — consistently and as soon as possible. Factoring cash flow into decisions distinguishes successful leaders. After all, wages, bills, and debt must be paid.

Conclusion

Well-prepared, readable financial statements provide a clear picture of an organization’s financial health and are essential to informed decision making. Applying the five key insights detailed here will improve business acumen, make the “language” of finance more approachable and understandable, and help connect daily work with the organization’s grander purpose. Without becoming a CPA or financial analyst, everyone can learn a bit more about financial statements and take a degree of responsibility for the short- and long-term fiscal well-being of their workplace. Perhaps such acumen has never been more important.

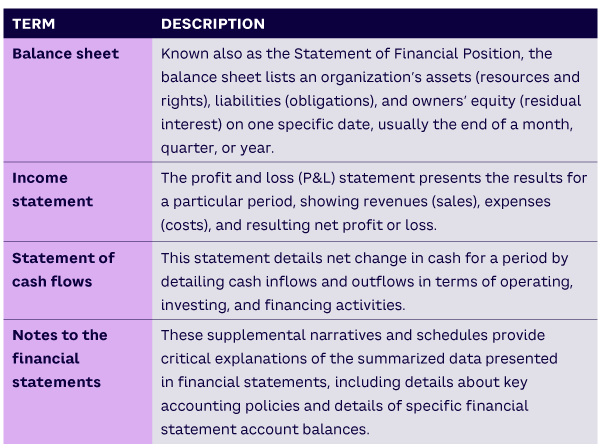

Appendix: Financial Statement Overview