AMPLIFY VOL. 36, NO. 12

Karen E. Linkletter explores contemporary and historical perspectives on assessing and developing leadership character. She delves into the question of whether or not character can be learned by examining the viewpoints of philosophers and management gurus. She also explores the liberal arts ideal, which emphasizes education and self-development, contrasting it with modern frameworks such as the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) and the Ivey Leader Character Framework (ILCF). Linkletter highlights the shift in focus from virtues like integrity and prudence to decision-making capabilities in contemporary character models.

There is a plethora of literature on leadership. For years, work on leadership emphasized the importance of performance and results. What kind of leadership was most effective for organizations to achieve their goals? Did leaders need to have a range of styles to pivot as needed when leading different kinds of people? Or did organizations need to bring in specific kinds of leaders (authoritarian, servant, transformational) as the institution faced new challenges and situations?

Every few years, we seem to revisit the topic of leadership and character as we watch leaders guide their organizations toward unethical or downright criminal ends or use questionable means to achieve what might be admirable goals. Sam Bankman-Fried’s FTX empire crumbled despite its alleged commitment to altruism and ethical use of wealth. Doctors Without Borders issued a video apology for its racially insensitive fundraising materials that featured white doctors treating Black and brown patients, in spite of the fact that many of the doctors participating in the program come from other ethnicities and cultures.1

It’s not surprising that many people have lost faith in the prominent institutions such as business, government, and education. If leadership has lost its compass, what does it matter that it is effective in achieving its goals? And what of ineffective leadership that resorts to any means necessary simply to survive? What is the purpose of leadership? What are its key tools?

These questions have revived an age-old conversation about the relationship between leadership and character. We are clearly in a phase where character has reentered the leadership conversation. But how do we, in the 21st century, assess, measure, and develop what we perceive as character? What constitutes character in today’s leaders? Can it be boiled down to specific behaviors or traits? Is it a product of one’s experiences, worldview, culture, or upbringing? In short: can character be learned or developed, or do leaders come to us fully formed?

This article explores contemporary and historical ways of assessing and developing character with the goal of providing a holistic approach. Contemporary frameworks for understanding and assessing leader character typically involve evaluating individuals using a set of qualities attributed to good leadership. Such models assume these character traits can be learned and developed through training and self-improvement. These frameworks can be effective in leadership character development in organizations, but theories of leadership character rooted in philosophy, psychology, and other disciplines may be just as (or more) effective in identifying and cultivating leaders.

For instance, management theorist Peter Drucker was an early proponent of character as a crucial component of leadership. Drucker argued that values, virtue ethics, and worldview shaped human character over time. Character, he believed, was less about a specific set of traits and more an internal perspective that shapes decision-making. Although contemporary models of reinforcing certain character traits and qualities may be helpful, it is also useful to consider a holistic, interdisciplinary approach that acknowledges the historical context of character and recognizes the role of ethics and experience in developing character.

Historical Views of Character

Aristotle & the Nicomachean Ethics

Classical Greek society is often referred to as the cradle of democracy. By the 5th century BCE, free males were expected to participate in political decision-making in democratic assemblies. These individuals needed to be educated and articulate enough to take on leadership responsibilities in Greek society.

Philosophical figures presented various approaches to creating such a citizenry of leaders. The Sophists believed in training people to develop arguments using evidence and rational explanations for positions. Contrasting theorists feared this approach would lead to a group of leaders who were gifted orators but not necessarily grounded in truth. These contrasting theorists included Plato and Aristotle.

Aristotle believed the search for truth and wisdom was the foundation of virtue and the key to character in political leadership. He argued that character is a product of education over a long period and requires continual practice — that is, virtuous behavior is formed by habit. An individual embraces virtuous behavior not by following a prescribed set of rules or directions, but by developing a true sense of what is right in a given situation. In other words, character is not developed by reading a list of things to do or not to do; it is developed by inculcating an instinct and a desire to do what is right. People are not virtuous by happenstance; it takes years of deep, personal work and consideration of circumstances and challenges to develop what we today might call a true moral compass that leads to integrity. Rather than a learned behavior, it is an intrinsic part of a person, developed over years devoted to introspection, learning through mistakes, and the study of ideas.

Aristotle’s complete list of virtues is complex, but his four essential virtues are:2

-

Prudence

-

Justice

-

Temperance

-

Courage

The Liberal Arts Ideal

Aristotle’s philosophy of virtue ethics assumed people would put their character into practice. That was the whole point: Greek society needed citizens who could lead and participate in decision-making. But, Aristotle pointed out, the leaders needed training and education. What would this look like? This was highly debated, but the idea of a liberal arts education grew out of this early conversation. The concept was that because moral virtue requires education, there needed to be some course of exercise for individuals as society grew larger. What did this education look like? What would lead to the ability to discern the meaning of prudence, justice, temperance, and courage?

Eventually, German, British, and American universities and colleges would embrace the ideal of a broad education, training people (at first, elite males) to be leaders or participants in representative government. In the German universities, the concept of “Bildung” encapsulated not only a course of study, but a spiritual path of self-development and awakening. In the American and British institutions of higher learning, the concept of the “gentleman” reflected the German ideal of Bildung. By the 1800s, a liberal arts education was believed to shape young men’s character by instilling values and beliefs that would be needed to participate in free government. These values included modesty, respect for justice and truth, frugality, and discipline of mind and temperament.

As Western societies became more industrialized in the late 1800s and early 1900s, universities emphasized specialized fields of study and research, and the liberal arts ideal began to fade (except at small, elite schools, where the liberal arts curriculum was still valued and offered). Today, some argue that the liberal arts have become irrelevant to modern life, and many students demand that higher education deliver marketable skills. Others take the position that a liberal arts education is even more critical in an increasingly volatile world.3 At any rate, a liberal arts curriculum today maintains a connection to developing people of character.

Drucker’s View of Character

Drucker posited that management was a liberal art, tied not only to practice, but also to wisdom, knowledge, and self-knowledge. Character is crucial to Drucker’s ideas on management and leadership. For Drucker, management was ultimately about people: “their values, their growth and development … [it] is deeply involved in spiritual concerns — the nature of man, good and evil.”4 He referred to integrity as the ”touchstone” of leadership, integral to any effective exercise of leading others in an organization.

Drucker states that although integrity is difficult to define, its absence is often revealed in behaviors and characteristics. Leaders lacking in integrity will, for example, concern themselves with who is right rather than what is right in a given situation. They also tend to fear strong subordinates because they lack the confidence to surround themselves with competence. Leaders without integrity also focus on other people’s weaknesses and fail to recognize their strengths.5

Ethics of Prudence

Drucker also embraced a model of virtue ethics. Although his explanation of ethics was quite sophisticated, he made a case for a Western philosophical perspective based on prudence: the ability to exercise self-control and govern one’s behavior with judgment. Drawing on Aristotle, Drucker argued that prudence is an important virtue because it requires one to put character into practice. Similarly, Drucker stated that virtue ethics, in the form of prudence, requires an internalization of what is right: “The Ethics of Prudence does not spell out what ‘right’ behavior is. They assume that what is wrong behavior is clear enough — and if there is any doubt, it is ‘questionable’ and to be avoided.”6

By following prudence, according to Drucker, one becomes a model of leadership character. Integrity and prudent behavior are linked as the two key elements of character for Drucker. In neither case does one learn a set of “right” and “wrong” actions or work toward developing certain strengths. One either has this sense, or one doesn’t.

Contemporary Models of Leadership Character

VIA-IS

The Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) was developed in 2004 by psychologists Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman.7 Their idea was to build on scholarship that emphasized developing people’s strengths rather than identifying weaknesses that needed to be addressed (the traditional realm of psychology as practiced using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). The VIA-IS (as well as the LCIA tool, described below) allows for both self-assessment and 360-assessment that involves data from peers and others.

Peterson and Seligman identified six virtues aligned with 24 strengths. The model has been updated as researchers have collected data from VIA-IS assessments of more than 13 million people worldwide:8

-

Wisdom and knowledge — creativity, curiosity, judgment, love of learning, perspective

-

Courage — bravery, persistence, honesty, zest

-

Humanity — love, kindness, social intelligence

-

Justice — teamwork, fairness, leadership

-

Temperance — forgiveness, humility, prudence, self-regulation

-

Transcendence — appreciation of beauty and excellence, gratitude, hope, humor, spirituality

The goal of this framework is to find character strengths that are trait-like (remain relatively stable over time), are applicable across time and culture, and can be measured empirically. The VIA-IS model recognizes that not every character strength is present in every individual; the point of the model is to focus on the strengths that exist and work with individuals to develop those.

ILCF/LCIA

The Ivey Leader Character Framework (ILCF) is a method used to evaluate aspects of leadership character. In 2015, the Ivey Business School and Sigma Assessment Systems partnered to create the Leadership Character Insight Assessment (LCIA) tool, which is used to measure specific dimensions of leadership captured in the ILCF. The project was the result of research conducted by Ivey related to the 2008 financial crisis. Researchers found that individuals employed by firms engaged in mortgage transactions that precipitated the crisis were either unwilling or unable to halt behaviors that created the problem. Short-term financial gain outweighed better judgment for upper management. At lower levels of organizations, employees felt powerless to speak out against what they knew was wrong behavior.

In essence, Ivey researchers discovered that the problem was not just a lack of character on the part of leadership, but also an organizational inattentiveness to the importance of character as part of the institutional mission. Ivey teamed with Sigma to create the LCIA as a means of: (1) identifying and measuring leadership character and its components and (2) helping organizations find ways to develop and grow character in their people.9 ILCF focuses on behaviors rather than specific traits, thus emphasizing the possibility of developing habits that embody character. In this view, character can be developed through acquisition.

LCIA places judgment at the center of its model of character; all other elements radiate outward from that virtue (“leader character dimension,” in the wording of LCIA). Drawing on similar components of character from VIA-IS, LCIA has 10 additional leader character dimensions:

-

Courage — makes decisions

-

Drive — momentum and productivity

-

Collaboration — effective in teams

-

Integrity — trust, transparency, effective communication

-

Temperance — risk management

-

Accountability — commitment to decisions

-

Justice — fairness, above and beyond

-

Humility — continuous learning, acknowledges mistakes

-

Humanity — understanding of stakeholders

-

Transcendence — inspires innovation, commitment to motivation

For the creators of LCIA, character is not just about ethics and intentions. It is about the ability to make sound judgments in the face of any situation, as exhibited by behavior. Technical competence and ability are not indicative of character under this model. Neither is it always about ethics. Rather, it is about the ability to sustain well-being and excellence. LCIA’s model of character is less about virtue ethics than about decision-making capability.10

Insights

What Is Character?

The concept of character has a long history, and we have adapted the definition of “character” over time to fit cultural changes and perspectives. Character is not a set of behaviors, but rather a mindset, according to Drucker. This is much in line with Aristotle. Both Aristotle and Drucker established a clear set of virtues that constituted character. Although Aristotle’s system of ethics was complex, he emphasized four moral virtues. For Drucker, integrity and prudence were the two virtues that establish leadership.

More modern visions of character focus on personal development. How can one develop behaviors that reflect character? How can self-improvement lead to better character? For these modern leadership models, character is not just about integrity or prudence. VIA-IS takes a very individualized view of character, identifying specific strengths that are unique to each person. Not everyone will have all of the 24 strengths that align with the six virtues.

These strengths have been modified over time by the system’s developers based on their experience with assessments. For example, the updated VIA-IS no longer includes integrity as a strength under the virtue of courage; that has been replaced with “honesty” as a strength (perhaps because integrity is difficult to quantify). LCIA includes integrity as one of its character dimensions, but it is not central to the model. Both VIA-IS and LCIA include justice, temperance, and courage, but prudence is either absent or included under temperance. Aristotle’s four primary virtues remain elements of modern character, but prudence is minimized in its importance.

Clearly, leadership character can be defined in many ways depending on what one prioritizes. If decision-making ability is most important, then judgment will be central to character. If character is based on the presence of individual and variable strengths, then the development of individual qualities unique to each person will determine that person’s leadership abilities. If building trust and consistency of behavior is the primary component of character, then leadership assessment will prioritize integrity and prudence.

The definition of leadership character, however, invites us to ask: what is the purpose of leadership? If the focus is on individual decision-making ability or development of individual strengths, where is there room for consensus development and team building? If leaders only focus on self-development, how do they learn to think in terms of shared values and culture?

How Does One Acquire Character?

This is a question that dates to Greek and Roman societies. The liberal arts curriculum was the subject of much debate in Aristotle’s time, for example. And how did one actually practice virtue?

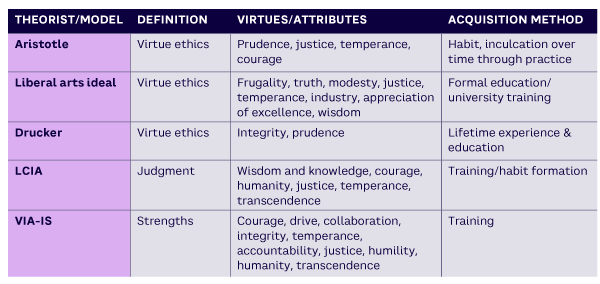

Table 1 presents definitions of character, associated virtues and attributes, and methods of character acquisition for the historical and more contemporary models discussed in this article. There is some overlap between virtues in the LCIA and VIA-IS models. For example, both share courage, humanity, justice, and temperance. The liberal arts ideal includes wisdom, temperance, and justice and adds a few unique traits, including frugality, truth, modesty, appreciation of excellence, and industry.

Older models of leadership character assume that character cannot be acquired by strengthening certain traits or behaviors. For Aristotle and Drucker, character was something formed over one’s life (and, in the case of the liberal arts ideal, through formal education). Drucker was very clear about this:

Character is not something managers can acquire; if they do not bring it to the job, they will never have it. It is not something one can fool people about. A person’s coworkers, especially the subordinates, know in a few weeks whether he or she has integrity or not. They may forgive a great deal; incompetence, ignorance, insecurity, or bad manners. But they will not forgive a lack of integrity. Nor will they forgive higher management for choosing such a person.11

This is not to say that people cannot grow and change. Drucker advocated focusing on people’s strengths and developing them, rather than zeroing in on their flaws and weaknesses. But, like Aristotle, Drucker believed that a true moral compass could not be developed if one had not done so early in life. In other words, integrity could not be formed by leadership training.

Because contemporary models of leadership character assessment do not place as much emphasis on integrity and prudence, they provide room for personal development. VIA-IS allows for individual paths to character development. Because not every person has every strength, the process of character acquisition and improvement will depend on the individual. With its focus on sound decision-making, LCIA lets people identify aspects of their character that may be inhibiting them from exercising judgment on a consistent basis. This will vary considerably from individual to individual. One person may be less willing to admit mistakes while another might not always consider the full range of stakeholders impacted by a decision.

But this begs the question: can people learn the crucial elements of integrity and prudence later in life? Contemporary leadership character models can help an individual learn to exhibit integrity and prudence (via lists of behavioral dos and don’ts), but is this truly a reflection of character? Or is this behavior that is not internalized, not really part of who the individual is? Organizations need to think through the possibility that people who don’t have integrity as adults may never be able to learn to be so (save for a life-altering event).

Perhaps Drucker was right. As much as we might want to help leaders improve in this crucial area, it may be wise to weed out those who lack integrity and a sense of prudence before they become a problem in our organizations.

Conclusion

Americans have been trained to recognize character through their leaders. George Washington was a leader of character because, as his biographer Mason Locke Weems wrote, Washington was honest enough to tell his father about damaging a valuable cherry tree when playing about with his axe when he was a child. The story is fiction, but it presented Washington as a figure of virtue: one who put integrity and honesty in the fore.

Definitions of character may change, but most people know the absence of what they would define as character when confronted with it.

Contemporary leadership character assessment and development tools, such as LCIA and VIA-IS, emphasize specific dimensions or strengths that can be measured. Although such models are helpful for both self-assessment and leadership development programs, it is probably worthwhile to step back and consider the nature and process of character development from a historical perspective.

In the liberal arts tradition and the view of management theorist Peter Drucker, character is something formed over many years. One’s view of the world, perception of people, approach to problem solving, ability to withstand uncertainty, willingness to be honest and admit mistakes, and a host of other qualities we associate with character are not created overnight or in one leadership seminar.

We can certainly work to improve our strengths and augment our toolboxes, but we are indeed byproducts of our pasts, which make us the unique, imperfect individuals we are.

A holistic understanding of leadership character’s essence and development will be helpful in facing the challenges of the future.

References

1 Leger Uten Grenser. “Anti-Racism: When You Picture Doctors Without Borders, What Do You See?” YouTube, 6 December 2022.

2 Aristotle. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Reprint edition. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

3 Pasquerella, Lynn. “Yes, Employers Do Value Liberal Arts Degrees.” Harvard Business Review, 19 September 2019.

4 Drucker, Peter F. The New Realities. HarperCollins, 1989.

5 Drucker, Peter F. Management. Revised edition. HarperCollins, 2008.

6 Drucker, Peter F. “Can There Be ‘Business Ethics’?” In The Ecological Vision: Reflections on the American Condition, edited by Peter Drucker. Routledge, 2011.

7 Peterson, Christopher, and Martin E.P. Seligman. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Clarification. American Psychological Association/Oxford University Press, 2004.

8 Littman-Ovadia, Hadassah, et al. “Editorial: VIA Character Strengths: Theory, Research and Practice.” Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 12, April 2021.

9 “Leader Character Insight Assessment (LCIA).” Sigma Assessment Systems, 2013.

10 Crossan, Mary, William Furlong, and Robert D. Austin. “Make Leader Character Your Competitive Edge.” MIT Sloan Management Review, 19 October 2022.

11 Drucker (see 5).