AMPLIFY VOL. 38, NO. 1

Mary Jacobs just returned from an unexpected meeting with her CEO where he invited Mary to take a new role as chief sustainability officer (CSO) of Exactibrate Corporation. Exactibrate, headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio, is a publicly held company that manufactures production, process, and testing equipment for semiconductor chip fabricators. With 12,000 employees and US $13 billion in annual revenue, Exactibrate has manufacturing facilities in Cleveland, Rio Rancho, New Mexico, and a newly opened facility outside Berlin, Germany. The EU hopes to produce 20% of the world’s chips by 2030,1 and Exactibrate entered the market with the goal of becoming the leading supplier to this region.

Mary took a class in corporate social responsibility during her MBA studies at Case Western Reserve University a decade ago, but her work in the company’s marketing and sales group never called on that learning. Mary’s mandate from the CEO, to whom she will report, is to reconcile the company’s fragmented efforts around sustainability, with two goals: (1) develop an integrated sustainability program that creates positive economic returns for the company and benefits communities where it operates and (2) boost the company’s competitive position as a cutting-edge manufacturer. Mary lacks detailed knowledge about the state of sustainability at Exactibrate, but four concerns came quickly to mind:

-

She knows the company has described its capacity as “moderate” in sustainability reporting. The accounting group had some level of sophistication, but she knows they have not fully incorporated Sustainability Accounting Standards Board principles and frameworks into their work. There are gaps in data collection and reporting across a broad spectrum of reporting areas, and she wonders how the company’s US-based group will handle more stringent EU reporting requirements.

-

The company’s plant in Rio Rancho, colocated with a major Intel plant, is a heavy user of water. That’s fine in the humid Midwest, but arid New Mexico has experienced drought conditions for several years, and the future of water supplies in the Western US looks more under threat with each passing year.2,3 Exactibrate’s water costs continue to rise, but leaders have made little effort to reduce water consumption. Costs aside, Mary has concerns about the plant’s long-term viability, given ever-tightening water supplies.

-

Semiconductor chips use as inputs (and produce as byproducts) several toxic chemicals, including PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances).4 In her marketing role, several European customers had reached out about potential manufacturing and process solutions to this issue that her company might have or can develop to help reduce the use and/or impact of these chemicals.

-

Cleveland, the company’s home, has the lowest median household income and second-highest separation and divorce rate in the country, as well as one of the highest violent crime rates.5 Other than employing 6,000 people in northern Ohio, Exactibrate’s only community involvement has been a donation to the Cleveland Orchestra. The community needs wage growth, financial literacy, work on preserving families, and improvements in education and training. What role can the company play in improving community sustainability?

Mary’s challenge is not unique. Exactibrate, like many companies, faces several sustainability issues that seem unconnected. For Mary and many like her, a change of mindset is the first step. Rather than a few individual efforts with a variety of short- to medium-term time horizons, sustainable sustainability is a long-term journey across several areas of impact.

Having a good map helps during any journey, and this article provides one in the form of a Sustainability Canvas designed to help CSOs and other leaders create an integrated, ongoing sustainability program that creates economic, social, and strategic value for a business and its communities.

Defining the Compass Points

Just as north, east, south, and west anchor geographic maps, the Sustainability Canvas orients around four foundational compass points. The first considers two areas of business activity: (1) those internal to the company and (2) those that interact with external audiences. Many of a firm’s internal processes, from expense report accounting to Six Sigma quality initiatives, satisfy the needs and concerns of internal stakeholders, such as employees, investors, and regulators. Other processes, such as R&D and advertising campaigns, create products or services that the business provides to external stakeholders, including customers, supply chain partners, and the communities where the business operates.

The other set of compass points considers two arenas where all businesses operate: (1) private markets and (2) the public square. All firms depend on private markets for key resources, such as supplies (from raw materials to intermediate to final goods), labor (employees and subcontractors), financial (private banks or public markets), and reputation (brand and recognition). All firms participate in the public domain as well, which includes everything from paying taxes and making voluntary philanthropic donations to following laws and regulations, using existing community infrastructure, and proactively investing in new infrastructure or resource development.

4 Destinations/Areas of Focus

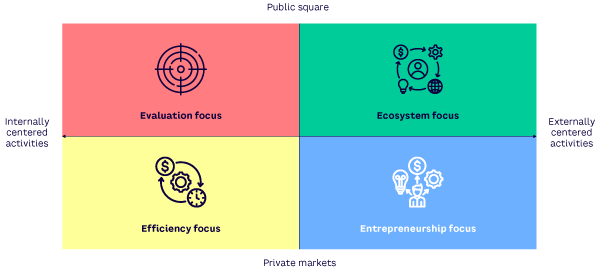

Figure 1 shows the four anchors of the map and describes the four destinations (or focus areas of sustainability). We classify each focus area as its own quadrant, and many of our partners find it helpful to use the associated color scheme to name them.

The “red quadrant” (internal activities of interest to the public square) focuses on measurement and assessment, including evaluation and compliance with existing laws, norms, and regulations. Common measures of concern include carbon footprint; Scope 1, 2, and potentially 3 emissions; waste produced; and measures of social concern, such as social impact of philanthropic programs, controls for human trafficking in the supply chain, and wage and benefit fairness among employees. A sustainability report (of interest to customers, regulators, environmental/social activists) and other compliance reports constitute this quadrant’s outcome or work product.

The “yellow quadrant” (internal activities that focus on private markets) focuses on efficiency and cost reduction. The easiest way to define this quadrant is the supply chain: inbound supplies and logistics, manufacturing, and outbound logistics. This quadrant creates the data that the red quadrant captures and reports. Activities in the yellow quadrant include reducing energy use, eliminating waste, and/or improving the overall efficiency and productivity of the firm. Projects that reduce the firm’s resource footprint or improve productivity usually reduce its overall cost position over medium- or long-term time horizons. Mary’s concern about water usage at the Rio Rancho plant is a yellow quadrant activity. Sustainability projects here would aim to reduce overall water usage and improve how productively the firm uses each gallon, including recycling and purification for discharge into the community. Sustainability becomes sustainable as it drives down costs and improves efficiency.

The “blue quadrant” (externally focused activities in private markets) offers a new way of thinking about sustainability for many executives. This is the quadrant of products, services, and revenue, and the question of how to leverage a company’s expertise to create new sustainability-based revenue streams too often goes unasked. Leaders can often find potential products in their yellow quadrant activities. Creating sustainability within the four walls of the firm may result in new processes (and sometimes new patentable solutions) that become the basis of monetizable innovations. At the very least, the firm may provide consulting services to other companies facing similar issues. For Exactibrate, the European customers clamoring for help with their own sustainability problems convey two important messages: (1) customers see the company as competent in sustainability and (2) they are likely to see Exactibrate as a leader in this area. That constitutes a set of warm leads for sales and marketing efforts.

The “green quadrant” encompasses what in an earlier age was called “corporate social responsibility.” This is the quadrant of external activities targeting the public square (the community and larger social ecosystem in which the business operates). Philanthropy comes to mind for most people as a go-to activity to build communities, but donations are just the tip of the iceberg. For example, scholarship programs help a few in the community while mentoring and other knowledge-sharing programs benefit hundreds or thousands. Rather than just donate funds to the symphony, as Mary’s company does, effective ecosystem building invites businesses to share their expertise, knowledge, and skills in ways that help communities solve complex and enduring challenges. One often overlooked contribution is for a company to act as a “convenor” and leverage its network connections to build awareness and critical mass around pressing issues.

The Sustainability Canvas shows how leaders can integrate their sustainability efforts. Every organization has some activity in each of the four quadrants of sustainability, and one role of a CSO like Mary lies in leveraging learning from activities in one quadrant across the map. For example, red quadrant evaluation and compliance activities may suggest low-hanging fruit for yellow quadrant efficiency-enhancing projects. Those projects may suggest potential blue quadrant products and/or services, some of which may help strengthen a green quadrant ecosystem. This represents one level of integration across quadrants. Another type of integration requires understanding how each of these quadrants creates value for both shareholders and stakeholders, which we consider next.

How Each Quadrant Helps Shareholders & Stakeholders Win

Mary’s mandate includes creating economic value for Exactibrate’s shareholders and social value for its stakeholders. In accepting this, Mary adopted an important perspective that denies the existence of a “sustainability tax” — the idea that executives must choose between economic and social value or between shareholders and stakeholders.

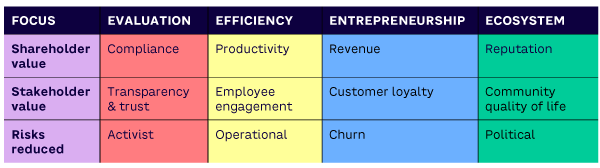

This represents a critical evolution in the sustainability journey because abandoning sustainability tax thinking means that leaders only execute projects that create value for all: investors, customers, employees, suppliers, regulators, and the community. In this section, we outline the ways that actions in the quadrants create value for all. Table 1 shows the sources of value for each quadrant.

Shareholder Value

Shareholder value arises from either the current (and potentially future) earnings stream of the business or the multiplier on those earnings that creates the valuation of the firm. We all learned in Accounting 101 that a firm’s earnings equal its revenues minus its costs. By keeping the business compliant with regulatory requirements and other legal obligations, red quadrant activities reduce costs: firms avoid fines and related legal expenses. Yellow quadrant activities also reduce costs, either directly from lower resource use and less waste or indirectly by improving productivity. Blue quadrant activities grow top-line revenue. Green quadrant activities may not impact current or future earnings, but they impact the multiplier by building a positive reputation for the firm and/or brand equity among various stakeholders.

As a company travels further in its sustainability journey, it focuses on activities in each quadrant that produce long-term gains, including lasting efficiencies, recurring revenues, and/or an institutionalized brand and reputation. Thoughtful and careful sustainability initiatives increase the economic value of the firm — shareholders win.

Stakeholder Value

Stakeholder value can be measured in monetary terms, such as when sustainability work reduces the prices customers pay for products or when those products help them solve specific problems. Suppliers win when they get paid sooner, employees benefit from higher wages, and communities benefit from cash or in-kind donations that fund their programs. This usually represents the lesser source of stakeholder value; stakeholders also benefit when the quality of their interactions with the business and their lives in general improve.

Red quadrant activities improve the lives of stakeholders through transparent information, which sends a signal of respect from the business toward them and allows them to make informed assessments of the quality of the firm. Yellow quadrant activities improve their suppliers by making those interactions more efficient and effective. Employees win through greater levels of engagement, which may come through participating in this sustainability work or through the reputational benefits of working for a cutting-edge company.

Blue quadrant activities improve the quality of customer interactions through increased respect and trust. Exactibrate’s customers openly asked the company to help solve their issues. When companies listen to their customers, they not only develop better products, they also exhibit respect for them. That respect engenders trust between the parties, which lays a foundation for a stream of products and services that meet real customer needs and earn solid returns for the business.

Green quadrant activities, when done thoughtfully and well, improve the quality of life for the community. Everyone benefits when firms contribute their knowledge and skill — not just their money — to solving or mitigating deep-seated community challenges and issues. Cleveland residents may find their lives less stressed due to Exactibrate’s targeted work that focuses on urban renewal in its hometown. Just as with shareholder value, the Sustainability Canvas shows stakeholders where tangible societal value lies, and stakeholders win.

Risk Reduction

The third row of Table 1 shows how sustainability efforts in each quadrant reduce risk. Reducing risk benefits both shareholders (through less volatile earnings) and stakeholders (through more predictable behavior by the business). Red quadrant activities mitigate the risk of social activist pressure on the firm, such as boycotts. They also allow those activists to better understand and predict why the firm does what it does. Yellow quadrant efforts reduce operational risks such as safety or supply chain disruptions from climate events. Shareholders appreciate a more stable earnings stream, and stakeholders such as employees and suppliers prize workflows with fewer potential interruptions. Blue quadrant activities reduce customer churn, which stabilizes revenue streams and lowers customer-acquisition costs. Customers win because they avoid product-related disruptions, and they do not incur the search costs associated with finding a new supplier. Finally, green quadrant activities reduce political risks for the firm as it and its leaders fulfill their roles as good corporate citizens. The general citizenry benefits as they have (and know they have) a stable, predictable partner dedicated to improving the quality of life for all.

Competitive Advantage

The second half of Mary’s mandate includes a charge to create an integrated sustainability program that helps build and secure a stronger competitive position. A generation ago, Michael Porter advanced a simple thesis about successful strategy: firms won in their markets through either cost leadership or creating a differentiated offering.6

The logic of the Sustainability Canvas belies that notion. Yellow quadrant activities improve the firm’s cost position at the same time blue quadrant ones enhance competitive uniqueness. As firms become active in these two quadrants, they find themselves in the enviable position of beating competitors on both cost and differentiation. Green quadrant activities may contribute to dual advantage by lowering the firm’s political risk profile and associated costs while burnishing its reputation and raising social capital.

We don’t know who Mary’s competitors are, but as she uses the Sustainability Canvas to create an integrated sustainability program, Exactibrate will gain advantages over its rivals. As she integrates efforts across all four quadrants, the firm will develop routines to both codify and share important knowledge. As discussed above, a truly integrated program shares knowledge and best practices across quadrants. Firms that adopt a learning or growth mindset develop a culture of continuous learning, improvement, and innovation. That culture bestows significant advantages over rivals that fail to integrate their sustainability programs and related learning.

Conclusion

Mary Jacobs isn’t real; she represents a composite of several directors or C-suite sustainability leaders we’ve met. But the challenges we posed for her are very real. Many firms engage in a series of short-term/one-off sustainability initiatives. Regardless of whether these activities are run from the corporate center or under the purview of division or business unit heads, they lack the strategic rationale and integration that come with placing activities on the Sustainability Canvas.

At a basic level, the Sustainability Canvas helps leaders understand where their efforts lie and where further investment should occur. Every firm engages stakeholders in each quadrant of the map (internal or external, market or public square focused) whether they intend to or not. The map helps leaders see where their efforts are opportunistic and reactive and where they are strategic and proactive.

At a higher level, the Sustainability Canvas helps leaders identify and exploit synergies across quadrants. How might learning and working in the yellow quadrant create opportunities for new blue quadrant products or services? How might better evaluation and measurement help the firm contribute to community ecosystem development? When organizations and their leaders create this type of integration, they leverage a flywheel effect that makes their sustainability programs self-reinforcing and self-perpetuating. When this happens, they’ve achieved sustainable sustainability.

References

1 Haeck, Pieter, and Leonie Cater. “Chemicals Ban Could Derail EU’s Chips Ambitions, Lobbies Warn.” Politico, 18 December 2023.

2 Prokop, Danielle. “Despite February Snows, New Mexico Drought to Continue.” Source NM, 6 March 2024.

3 Miller, Jen A. “Managing the Future of Water — In the West and Beyond.” Mines Magazine, 12 January 2023.

4 Haeck and Cater (see 1).

5 Perry, Alex. “5 Ohio Cities Among the Most Stressed in America, Study Finds. Is Yours One of Them?” Akron Beacon Journal, 29 July 2024.

6 Porter, Michael E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press, 1985.