AMPLIFY VOL. 38, NO. 1

Increasingly, companies are making bold commitments to deliver solutions to environmental and social challenges, spurred by customer, investor, and legislative pressures. To date, most organizations are struggling to live up to their commitments. A lack of strategic alignment within the leadership and management organization is often the root problem.

Companies will fail to achieve ambitious sustainability goals as long as managers treat sustainability as separate from the core business. Expecting aspirational targets to be reached via business as usual is wishful thinking. So is pursuing those targets without delivering financial value.

What’s needed is a fundamental reexamination of the business strategy — and how that cascades into aligned action — so sustainability becomes an integral part of how the firm creates value. This begins with executives (working with the board) but also requires aligned decisions and actions by managers and employees across the organization.

Moving from Aspirations to Results

Achieving bold sustainability commitments requires changing how business is done and a complete redesign of company strategy. Management consultant and author Roger Martin describes strategy as a cascade of choices that address five questions:1,2

-

What is our winning aspiration?

-

Where will we play?

-

How will we win in chosen markets?

-

What capabilities must be in place to win?

-

What management systems are required?

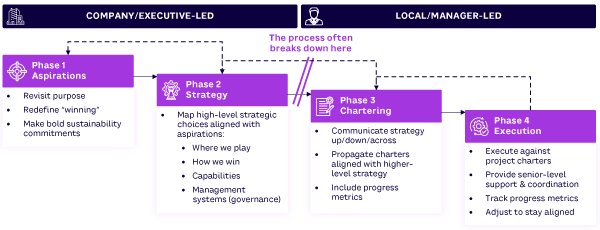

These questions must be addressed both at a high level by executives and through more specific choices at operational management levels. We break the process of strategic transformation into four phases: aspirations, strategy, chartering, and execution. Figure 1 shows why the flow between these phases is critical to achieving transformational results.

An aspiration defines what winning looks like. It incorporates the company’s purpose and mission, as well as its vision for success. Traditionally, corporate aspirations have been financially grounded, with purpose statements focused on meeting customer needs while delivering shareholder value. Sustainability recognizes the importance of meeting both shareholder and customer needs but goes beyond that to consider the stakeholders of the whole system in which a business operates.

Sustainability aspirations must be connected to the strategy cascade in a way that creates financial value while having a positive environmental, social, and economic impact. We refer to this as sustainable value creation.3 The logic for an integrated strategy must be clear, addressing potential risks while seeking opportunities to grow the business.

In the chartering phase, middle managers make strategic choices and frame the choices needed at the next level down. “The CEO may initiate the process, but the making and chartering of choices must continue all the way down the hierarchy for effective action to take place,” writes Martin.4

This is often where the process breaks down. Organizations struggle with the transition from phase 2 to phase 3: executives roll out a strategy and expect aligned implementation to propagate naturally from top to bottom. Unfortunately, this rarely happens on its own.

What may seem like a clear sustainability strategy to executives often fails to translate into a practical set of strategic choices for managers deeper in the organization and closer to the reality of the business. Without a relevant sustainability strategy for their part of the business, managers stick with business as usual, limiting progress toward corporate commitments. Operating under a traditional strategy, they treat sustainability initiatives as a distraction (or even something harmful to the business) rather than essential to creating business value.

Bridging the aspiration-execution (and results) divide isn’t simple, but it can be done. In this article, we use Trane Technologies, a US $17 billion manufacturer of sustainability-focused HVAC and refrigerated transport equipment and solutions, as an example. Trane Technologies has spent considerable time developing and implementing sustainability as a strategy.5

Integrating Sustainability Strategy: Starting at the Top

The most important prerequisite for chartering (defining, selecting, and executing) meaningful projects and activities that deliver on aspirational commitments is an integrated sustainability strategy that shows how they will strengthen the core business. Trane Technologies is a purpose-driven company with deeply embedded sustainability aspirations.6

These aspirations propelled Trane Technologies’s leadership to set ambitious 2030 Sustainability Commitments, especially around greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs). The company is known for setting the “Gigaton Challenge,” which is designed to reduce its customers’ emissions by a gigaton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) between 2020 and 2030.7

It also developed a metric to measure a product’s lifetime emissions against its capacity (giving the industry a new Scope 3 standard to compare alternatives) and established a Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi)–approved goal to reduce the emission intensity of their products by 55% by 2030.8 These goals represent milestones in the company’s longer-term commitment to achieve net zero GHG emissions by 2050.

Moving from aspiration to clear strategy, the leaders at Trane Technologies developed a playbook to broadly map out how to successfully achieve the Gigaton Challenge.9 The playbook effectively addresses phase 2 (see sidebar “Trane Technologies Playbook for the Gigaton Challenge”).

Trane Technologies Playbook for the Gigaton Challenge

The strategy at Trane Technologies for achieving the Gigaton Challenge can be summarized using Martin’s strategy cascade:

-

Winning aspirations. Trane Technologies established clear 2030 commitments, including financial growth and reduced global carbon emissions.

-

Where to play. In 2020, Trane spun off its industrial business from Ingersoll Rand, creating a pure-play climate-control company. Today, the company focuses on products and services that have a significant impact on global climate change, including commercial and residential HVAC and refrigerated transport solutions.

-

How to win. Trane Technologies reinforced its competitive advantage by understanding its customers’ needs and translating them into products and services that improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions. This translation enables its customers to decrease operating costs and reduce their carbon emissions for an environmental and economic win-win.

-

Must-have capabilities. To deliver on these competitive advantages, Trane Technologies developed several must-have capabilities across its business, which can be grouped into two categories:

-

The core processes needed to achieve the Gigaton Challenge, including engineering and product management, sales and lifecycle service, communications and marketing, and global integrated supply chain

-

Resources and capabilities that fuel those processes, including product technology, human resources, information technology and data analytics, and process improvement capabilities

-

-

Enabling management systems. These systems integrate sustainability throughout the company to the highest level: the board of directors. They include creating standard systems for defining, reporting, and monitoring progress on key non-financial metrics as well as financial performance. For example, an internal publication, “Doing Our Part: Reducing GHG Emissions in Operations and Across the Value Chain,” helps employees understand the key levers driving emission reduction across all emissions scopes within its value chain and how they can support the strategy.

How the Gigaton Challenge Creates Sustainable Value

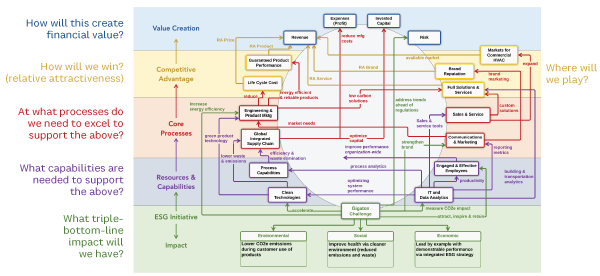

The Sustainable Value Creation Map (SVCM) in Figure 2 shows how the elements of Trane Technologies’s strategy link to create sustainable value10 and illustrates how sustainability initiatives can strengthen a company’s core business strategy. It depicts how an initiative can create sustainable value by mapping the cause-and-effect drivers. It connects the dots upward through the value chain to show how an initiative can build new resources and capabilities that strengthen core processes. These can create new competitive advantages in chosen markets that grow revenue. Core processes can also lead to operational improvements that lower operating expenses, optimize capital investments, and reduce risk. Together, these impacts combine to create long-term financial returns for company investors.

Figure 2 shows a high-level map of how the Trane Technologies Gigaton Challenge was applied to the commercial HVAC market. The sustainable business strategy is an interconnected system, linking elements from bottom to top along the value creation chain and across the functional areas of the business. Understanding these links is key to organizational alignment, but they are often assumed to be understood, taken for granted, or not made explicit — especially when moving from strategy to action.

The SVCM is a tool for exploring how a specific initiative can reinforce a company’s strategy for sustainable value creation (or how the company creates financial value) by increasing revenues, reducing expenses, optimizing capital, and/or reducing risk while pursuing sustainable impact environmentally, socially, and economically (sometimes called the “triple bottom line” or TBL).

Figure 2 shows how the Gigaton Challenge supports the business strategy in the commercial HVAC market while achieving positive environmental impact. The middle layers of the map incorporate key elements of Martin’s strategy choice cascade. The arrows depict cause-and-effect links between the elements. For the strategy to be financially sustainable, it must drive the elements shown in the value-creation layer at the top.

To illustrate the value-creation chain, one impact of the Gigaton Challenge is to accelerate the development of clean technologies, a strategic capability for the company that supports the core process of engineering and product marketing. This leads to energy-efficient products that enhance the firm’s competitive advantage in terms of product performance, increasing the relative attractiveness of products. This in turn drives revenue growth. The development of low-carbon technologies enables sales teams to offer new system solutions to customers, further driving sales and revenue growth by improving service, relative to competition.

These value-creating impacts are further reinforced by the other activities shown on the map that strengthen Trane Technologies’s brand reputation, reduce manufacturing costs, and reduce risk.

The Key to Chartering

A single map of a corporate strategy, no matter how clear, is not enough to inform “local” decisions that managers make across the business.11 For bold commitments such as the Gigaton Challenge, the logic of sustainable value creation must be clearly mapped at each level in the organization and across functional disciplines.

This is where sustainability aspirations often go offtrack. To achieve them, managers at all levels must go through a similar sustainability integration process in phase 3 that executives go through in phase 2. This includes mapping the strategy of an issue or opportunity in their area of responsibility (i.e., local) and showing how it impacts sustainability targets and creates financial value for the company.

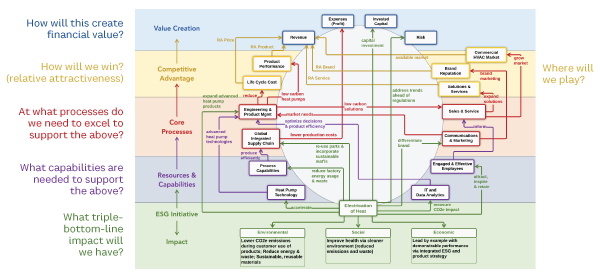

For example, heat pumps let customers shift from fossil fuel–powered climate-control systems to electric, where renewable energy sources can reduce carbon emissions. Cory Sauls, VP of the Project Management Office, Commercial HVAC Americas at Trane Technologies, created a project charter to accelerate the development of next-generation energy-efficient heat pumps.12 This is a high-level initiative requiring significant operating and capital investment, and it will drive the activities of hundreds of engineers and managers across a cross-section of Trane Technologies. Figure 3 shows the SVCM developed by Sauls to show how the “Electrification of Heat” (EoH) initiative creates sustainable value.

The top of the map shows how the initiative creates financial value by increasing revenue (market share), reducing operating costs, and reducing risk. These benefits must be weighed against the investments required to fund the project.

The middle layers of the map show how EoH connects to Trane Technologies’s higher-level strategy by reinforcing the company’s competitive advantage in the commercial HVAC market and strengthening its core processes, resources, and capabilities.

The left side of the map shows how accelerating the development of advanced heat pump technology fuels product development by engineering and product management.13

The resulting products enable marketing and sales to increase their win rate with customers and increase market share while commanding a price premium.14

The bottom section shows the sustainability impact of the initiative. It highlights the environmental benefits of decarbonization as well as the benefits of moving toward a circular supply chain model, which increases part reuse and incorporates more sustainable materials.

To gain executive support for this initiative, the project management office leader linked the project directly to the Gigaton Challenge and used the SVCM to depict on a single page how EoH connects to the corporate strategy to create sustainable value. This strengthens the chartering process in three ways:

-

It shows how an initiative addresses specific sustainability issues while building a business case for the initiative.

-

It highlights the key interdependencies between functional areas needed for the initiative to succeed. This is essential for identifying and enrolling the larger team needed to execute the project.

-

It points to specific metrics at each layer of the map that can be used to measure progress across the system. For example, some key metrics for EoH might include reductions in customer CO2 emissions (sustainability impact), new EoH products (core processes), market share in the commercial HVAC market (competitive advantage), and revenue from new EoH products (value creation).

The logic of the EoH strategy also makes it clear to members of the EoH team how their decisions need to align with each other. The team members add specificity to the strategy as they make consistent choices about how to work with suppliers, engineers, and the sales teams to develop and sell new heat pump solutions.

Of course, creating a frontline strategy is not the end of the journey. As the EoH team implements its strategic choices in phase 4 (execution) and encounters the constraints and uncertainties of the business, it is easy to get caught up in functional details and lose sight of the guiding strategy. Having a clear strategy map and revisiting it regularly helps team members maintain a clear line of sight to the higher-level roadmap, even as they learn and adjust. The problem-solving question becomes: “Does this decision support my team’s strategy for creating sustainable value?” Without this discipline, the game plan cascaded from the top can easily diffuse into disconnected local improvisation.

Supporting the Chartering Process from the Top

The roles played by company executives and management during the chartering process are complementary. Managers inform executives about market needs, operational strengths and weaknesses, and opportunities for innovation that can lead to revisions to the corporate strategy (revisiting phase 2).15 Similarly, the work of executives doesn’t end after a strategy is created and communicated. Executives and boards play a critical role in overseeing the chartering process, managing a portfolio of projects across the organization, allocating resources, and monitoring key metrics.

In addition to establishing a logical, integrated sustainability strategy from the top, executives can support the chartering phase in several ways:

-

Check for vertical alignment. This includes ensuring that key strategy cascade questions are being consistently asked and answered and that the answers are aligned with the top-level strategy.

-

Encourage horizontal alignment. Ambitious goals can’t be achieved in a siloed culture. Executives must encourage (and reward) managers to reach across boundaries and functions to optimize the whole system rather than focus narrowly on their piece of it.

-

Create a learning culture with upstream feedback. Well-designed and well-executed strategies don’t always produce intended results. Explicit permission from executives to learn and adjust is critical. As planning comes face-to-face with implementation or operational realities, higher-level strategies may need to be revised.

-

Build leadership competencies across the management ranks. Executives shouldn’t underestimate the challenges facing managers in leading change. It requires advanced competencies in systems thinking, stakeholder engagement, influence, emotional intelligence, sustainable business acumen, and strategic thinking. Providing managers with hands-on development of these leadership competencies should be part of the management systems developed in phase 2.

Achieving Ambitious Sustainability Commitments

At the end of 2023, Trane Technologies had reduced its customers’ carbon footprint by 157 million metric tons of CO2e and achieved 15.2% emissions per thermal ton reduction, based on its 2019 baseline.16

The company continues to identify opportunities to accelerate its progress toward its 1 gigaton milestone by 2030. This requires further embedding its sustainability strategy deep within the organization. The chartering phase continues to progress across the organization. Strategic realignment is iterative and complex, an inherently messy process. The challenge is to align the thousands of strategic and tactical choices managers at all levels make so they add up to something profoundly impactful and to not allow bold commitments to dissipate into the organizational abyss. And all this must be done while strengthening the business.

To maintain alignment across the organization, managers and employees need a line of sight to a clear corporate strategy, one that spells out the cause-and-effect drivers of sustainable value creation. Transformation then unfolds as local managers fill in the operational details and work across functions and departments to link their initiatives to those of others.

Transformation is hard, especially in large organizations. It requires constant rethinking, reconnecting, and retooling the elements of the business system in new ways. But this essential work must be done if companies are to walk the walk, meet their bold commitments, and help solve our world’s greatest challenges.

References

1 Lafley, A.G., and Roger L. Martin. Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works. Harvard Business Review Press, 2013.

2 Martin, Roger L. “Five Questions to Build a Strategy.” Harvard Business Review, 26 May 2010.

3 Hart, Stuart L. Capitalism at the Crossroads: Aligning Business, Earth, and Humanity. FT Press, 2007.

4 Martin, Roger. “Strategic Choice Chartering: Why Careful Chartering Is the Key to Great Strategy Choice.” Medium, 9 November 2020.

5 “Focusing for the Future.” Trane Technologies, 2019.

6 Trane Technologies is dedicated to integrated sustainability from top to bottom. Remuneration of top executives and leaders (approximately 2,300) is based on several metrics, including an ESG (environmental, social, and governance) modifier, performance factors such as GHG reductions internally and externally, and increasing gender and ethnic diversity in the company’s management. In addition, regional business sustainability councils develop business-specific sustainability strategies that support the company’s 2030 sustainability commitments; for more information, see: “Ambition. Action. Impact: 2022 ESG Report.” Trane Technologies, 2022.

7 Trane Technologies’s 2030 commitments include Leading by Example, the Gigaton Challenge, and Opportunity for All. Leading by Example focuses on reducing the company’s environmental footprint. The Gigaton Challenge focuses on helping customers reduce their footprint. Opportunity for All focuses on uplifting the company’s culture and communities.

8 The company’s 2030 Scope 3 target is to reduce product-use emissions by 55% per thermal ton below the baseline year of 2019 by 2030. This target is science-based and verified by SBTi.

9 “Gigaton Challenge Playbook.” Trane Technologies, accessed January 2025.

10 Mayberry, Matt. “The Sustainable Value Creation Map: Connecting the Dots Between ESG, ROI, and the Triple Bottom Line.” WholeWorks, February 2024.

11 Martin (see 4).

12 Note: this example has been simplified, both to protect confidential information and to make the connections clearer for outsiders.

13 New product development processes integrate sustainability considerations by requiring the use of a Design Systems for Sustainability and Circularity tool as part of the standard practice. This tool supports engineers and designers as they optimize new products’ contributions to the Gigaton Challenge.

14 A detailed analysis of these impacts would likely be needed before a significant initiative such as this would be approved. Supporting analyses could include a lifecycle assessment to estimate the impacts of EoH on lifecycle environment and health systems, including climate change. A more thorough financial analysis using a method such as net present value would also be required to quantitatively assess the financial returns from the project. The purpose of the SVCM is to depict the key drivers of value.

15 Polman, Paul, and Jeff Seabright. “Middle Management Is the Key to Sustainability.” Harvard Business Review, November-December 2023.

16 “2023 ESG Report: Accelerating Action for Impact.” Trane Technologies, 2023.