AMPLIFY VOL. 38, NO. 1

Imagine two hydropower facilities. One sits quietly on a river, generating clean energy for nearby communities while supporting fish migration through a carefully designed bypass system. The riverbanks around it teem with wildlife, and the facility hosts school visits to educate children about renewable energy and local ecosystems. This dam is a symbol of how sustainability and progress can work together.

The other facility, built decades ago, provides significant energy to a community but blocks migratory fish, disrupts water quality, and alters the surrounding ecosystem. Local communities downstream have seen declining fish populations, and Indigenous groups struggle to maintain cultural practices tied to the river. The dam’s benefits come at a visible environmental and social cost.

Both are renewable energy sources, but their impacts couldn’t be more different. So, which to choose?

Globally, the procurement choices of energy buyers (from large corporations and governments to small community utilities) have the power to shape the future of renewable development. All renewable energy development and generation has the potential to create negative externalities, but the health of the environment and those living near project areas don’t have to be sacrificed for the sake of these projects. Indeed, energy buyers are uniquely positioned to choose projects that put people and the environment first.

Today’s energy buyers emphasize only two criteria: (1) whether the electricity is renewable and (2) whether the renewable electricity comes from a newly built project. These criteria are important for the global transition to a clean grid, but they are insufficient to prevent putting renewable development on a collision course with biodiversity conservation and the rights of local communities. If we want a livable planet, we need more than just renewable electrons — we need a thriving environment and resilient communities.

Energy buyers can change the status quo by prioritizing energy sources that meet a high sustainability bar. They can consider a project’s environmental, social, and cultural impacts in addition to its generation attributes and better understand how energy generation integrates with its environment and community needs.

This is where the Low Impact Hydropower Institute’s (LIHI) holistic decision-making comes into play. Recognizing the need for comprehensive hydropower generation assessments, LIHI is leading an effort to ensure that energy projects align with environmental and social priorities. LIHI runs a certification program highlighting meaningful community involvement to understand project impacts and successfully promote restoration and improvement efforts. LIHI evaluates hydropower plants across the US and globally (through a partnership with the Hydropower Sustainability Alliance) on eight criteria: river flows, fish passage, water quality, preservation and protection of historic and cultural resources, species, habitats, shorelines, and public access.

LIHI’s approach to centering community perspectives and assessing a project’s environmental and cultural resource impacts is appropriate for hydropower anywhere in the world, including recent expansions in East Asia, the Pacific, and Africa.1 LIHI’s criteria can be used by developers to build projects and by energy buyers to test whether or not projects meet critical standards around sustainability.

This article focuses on hydropower, but the criteria can be applied to any renewable project in which buyers can choose energy development that prevents biodiversity loss and delivers benefits for local communities.

Hydropower Leads the Race in Renewable Energy Resources

Hydropower is a good example of the complexities facing sustainable energy solutions. It is highly supported in some sectors because it is reliable and renewable, but it has faced backlash due to its environmental and ecological impacts.2,3

Hydropower’s ability to match generation demand and help energy buyers meet their goals has secured its role as a vital component of the energy market. Nevertheless, to define effective goals for hydropower, we must acknowledge its history.

Large public projects were built all over the western US from the 1930s to 1950s. The hydropower projects constructed at that time still provide low-cost power to cities, but they were developed when consideration for ecological systems and local communities, particularly tribal groups, were not priorities. Some of these plants are targeted for removal by conservation groups (e.g., the Klamath dams in California), but energy operators and, ultimately, consumers depend on many of them for generation and system stabilization.

Many dams in the Northeastern US were built centuries ago to power small grist mills and sawmills. Historic mills later supported textile operations in Massachusetts and the paper industry in Maine. Over the years, these dams were converted from mechanical to electrical power (primarily small capacity, under 50 MW), providing a reliable renewable energy source. These small facilities provide baseload electricity and grid-support services such as spinning reserves. Although the output from one such facility might only power a small village, they are a grid-wide source of reliable, flexible power. Unfortunately, these dams impact ecosystems and were largely responsible for the extirpation of Atlantic salmon 100 years ago.

By identifying sustainability goals that consider historical realities, objectives can be effectively matched to facility operations, helping energy buyers become better informed and increasing the likelihood of gaining (1) hydropower owner support for improvements and (2) energy buyer support for hydropower generation.

Sustainability Priorities That Intersect with Hydropower Operations

At first glance, hydropower may seem at odds with sustainability principles, but its operations intersect with sustainability goals, sometimes beyond the scope of renewable energy. For example, the water is used to power turbines in a non-consumptive process that does not impact water quality. Also, hydropower projects have incredible longevity. Globally, the average hydropower plant is 30 years old. In the US, the average is 64, although many, especially in the Northeast, are more than 100 years old. Some of those use their original turbines to provide meaningful amounts of electricity and additional grid services.

One example is the Mother Ann Lee Project in Kentucky, which has been operating since the 1920s.4 It is located along the Kentucky River, which historically has had poor oxygen levels at certain times of the year. In 2005, the project voluntarily adopted an adaptive management plan to improve the river’s oxygen levels.

By prioritizing community benefits, accountability, and transparency and approaching hydropower through the lens of sustainability, hydropower can provide benefits to the environment, area habitats, and surrounding communities.

Community Benefits

One community benefit comes in the form of educational opportunities: introducing students to renewable energy and inspiring future careers in environmental science, engineering, and sustainable resource management. Exposure to hydropower operations fosters a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness between energy production, water management, and ecosystem conservation, equipping young learners with the knowledge and motivation to tackle future environmental challenges.

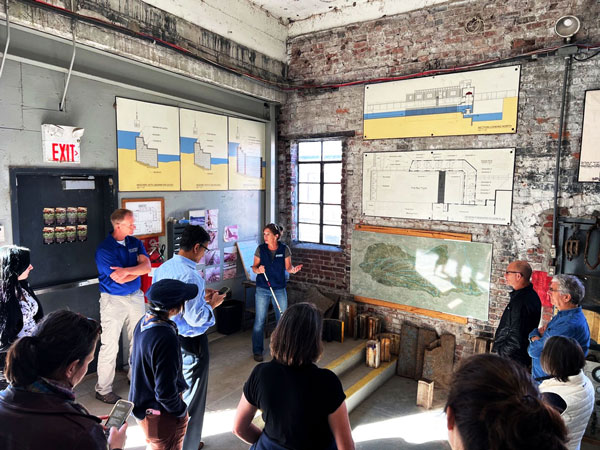

For instance, in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, the downtown hydropower facility routinely hosts school groups at its accessible powerhouse, which is downstream of a historic mill building erected in 1793 (see Figure 1).5 In Oregon, the Falls Creek Project hosts fourth graders yearly at its rural facility. Students learn about energy production and ecosystem preservation, reinforcing the significance of responsible environmental stewardship.6

The Bowersock Project in Lawrence, Kansas, takes community engagement a step further with a public partnership.7 When the plant added a second powerhouse, it tripled potential generation while also contributing to the circular economy by sourcing two used turbines for 2 MW of capacity. Bowersock Mills & Power Co. owns the dam, but the City of Lawrence is responsible for maintaining its structural integrity, as the reservoir is the source of more than half the city’s drinking water supply.

Bowersock manages the daily operations and ensures the reservoir is held at the appropriate level, lowering operating costs for the city’s municipal water operations. As a bonus, owner Sarah Hill-Nelson is working with regional stakeholders and conservation groups to create a recreation park upstream of the powerhouse that will include the restoration of native vegetation in the river corridor. Hydropower facilities like Bowersock are enhancing community engagement, fostering environmental literacy, and demonstrating the broader societal benefits of renewable energy investments by integrating public education with conservation efforts (see Figure 2).

Improved Biodiversity

Biodiversity is key to climate adaptation but is profoundly impacted by climate change.8 Hydropower operates on both sides of this equation. On the one hand, dams can prevent fish migration and slow flows, leading to warming waters. On the other hand, they can artificially create cool water sources for critical habitats.

Maine’s Freedom Falls Project is the first US installation of a new turbine design that is nearly 100% safe for downstream fish passage.9 Although small (350 kW), the design is highly efficient and provides evidence that turbines can be cost-effective and protective, eliminating the need for expensive screens that block the entrance of fish into the turbines but also reduce energy output.

Another good example is the Cutler Project in Utah, which created a buffer zone around the Bear River, protecting nearly 99% of the undeveloped area that encircles the facility.10 The owner also planted vegetation to create designated wildlife habitats and restore native plants and grasses.

Traditionally, hydropower facilities have been viewed as environmental disruptors, but even that can be a benefit. When the Bowersock Project went through relicensing in 2020, the owner actively considered adding fish passage to the dam to benefit local fish species (historically, there have been no anadromous fish species present in this stretch of the river). However, state and federal resource agencies were concerned with preventing the spread of invasive carp, which can wipe out native species. Native species have demonstrated the capacity to pass the low-head dam at high flows; invasive species have not. The dam now serves as a barrier and is the site of ongoing studies.

Municipal hydropower facilities have sometimes extended their environmental efforts to the larger regional state. For example, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) installed three hydropower facilities within its water supply infrastructure, which provides most of eastern Massachusetts with its drinking water.11 With no direct impacts on the environment, MWRA partners with the state's Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) to provide statewide watershed protection actions. MWRA also funds the DCR’s watershed management programs, in part from the sale of the project’s renewable energy credits.

Transparency & Accountability

Most hydropower facilities in the US are regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which posts all non-sensitive project documents to its e-library, an excellent source of technical information and a way for the public to participate in FERC licensing processes.12 This level of governmental transparency is somewhat unique globally and is the launching point for LIHI’s assessments. Globally, assessment needs to start earlier, beginning with assessments of whether or not developers deeply considered a project’s intersection with communities and ecosystems.

LIHI certifies hydropower that meets science-based criteria in eight areas of common impact, with more than 20% of facilities going above and beyond license requirements or the minimum LIHI criteria. The LIHI process also includes a framework for assessing renewable energy procurement options, which can serve as a guide for similar questions for solar and wind projects.

Like FERC, LIHI’s process is open and incorporates public comment into its certification decisions. Unlike FERC, LIHI’s review cycle is 10 years with yearly compliance demands (FERC’s cycle lasts between 30 and 50 years). In many countries, if a license is required, it is often issued for life. LIHI publishes individual webpages with materials and information on each of its 186 active certified projects (and more than 300 facilities), providing a point of contact and regular updates for those facilities.

Energy buyers concerned with transparency and environmental performance can encourage LIHI certification of a project under consideration. Doing so can cause direct improvements to a facility well before a license proceeding. In the US, if a FERC license proceeding is imminent, it can influence its outcomes. Energy buyers can also leverage LIHI’s certification program to gain additional insight into the diversity of a project’s impacts.

More than a third of FERC hydropower licenses in the US will be up for renewal in the next 10 years. This is the ideal time to outline sustainability priorities and identify hydropower facilities that meet energy needs and improve environmental and social outcomes. Many projects already provide such services. With the right encouragement, others could integrate sustainability practices under their existing licenses or address provisions in an upcoming relicensing process. In essence, if a potential energy buyer requires sustainability, project owners will be incentivized to act, and long-term purchase agreements can provide the financial stability necessary to carry out improvements.

Note that of the nearly 100,000 dams in the US National Inventory of Dams, only about 3% have hydropower. Although dams writ large are responsible for significant impacts on species and their habitats, water quality, flows, and access, thousands of non-powered dams that serve useful purposes (and thus are not contenders for removal) could produce enough energy to support millions of homes if retrofitted with hydropower.13

Globally, new dams are being considered for construction to address changing rain patterns driven by climate change. These dams have the potential for hydropower, and those potential hydropower projects could be designed to safeguard the environment and use new technology that protects migrating fish. However, developers need incentives to adopt designs that are (or may be) more expensive in the short term but avert the costs of harmful externalities in the long term.

The Critical Influence of Energy Buyers

Energy buyers can ensure that renewable energy choices contribute to long-term resilience by integrating broader sustainability goals into procurement processes. This means looking beyond immediate energy needs to address each project’s social, cultural, and environmental impacts. Asking the right questions can encourage innovation, foster collaboration with local stakeholders, and set a higher accountability and community engagement standard.

In this age of simultaneous crises, it isn’t enough to ask for new megawatts. Energy buyers should ask how those megawatts protect biodiversity and local communities. All projects have an opportunity to do things differently, and the time for one-dimensional decision-making is over.

Renewable energy has the potential to power the grid and drive positive change, shaping a future where economic growth and ecological health coexist.

References

1 “2024 World Hydropower Outlook: Opportunities to Advance Net Zero.” International Hydropower Association (IHA), accessed January 2025.

2 “Hydropower Enjoys Broad Public Support.” National Hydropower Association (NHA), accessed January 2025.

3 “Profiling the Top Pros and Cons of Hydroelectric Power Generation.” NS Energy, 25 June 2021.

4 “LIHI Certificate #24 — Mother Ann Lee Project, Kentucky.” Low Impact Hydropower Institute (LIHI), accessed January 2025.

5 “LIHI Certificate #11 — Pawtucket Project, Rhode Island.” LIHI, accessed January 2025.

6 “LIHI Certificate #4 — Falls Creek Project, Oregon.” LIHI, accessed January 2025.

7 Bowersock Hydropower website, 2025.

8 “Biodiversity — Our Strongest Natural Defense Against Climate Change.” United Nations (UN), accessed January 2025.

9 “LIHI Certificate #178 — Freedom Falls Project, Maine.” LIHI, accessed January 2025.

10 “LIHI Certificate #62 — Cutler Project, Utah.” LIHI, accessed January 2025.

11 Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) website, 2025.

12 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) eLibrary website, 2025.

13 Kimani, Alex. “90,000 Dams in America: Just 2,500 Produce Hydropower.” OilPrice.com, 22 March 2022.