AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 3

Cities often struggle to successfully develop strategies for implementing policy measures; reasons for this struggle include public and political acceptability, funding and legislative issues, administrative restrictions, and skills shortages.1 This is especially true for the transport sector as it works to meet the goals and targets set out in the European Green Deal. The concepts are quite different from the urban planning strategies of the last two decades and require city planners to use forecasting and backcasting models and to develop cross-sectoral master plans. These skills are not prevalent in smaller cities and disappear altogether in rural and peripheral areas.2,3

Recognizing this, the European Commission included two methodologies in its 2013 urban mobility package: sustainable urban mobility plans (SUMPs) and sustainable urban logistics plans (SULPs).4 A SUMP is a consolidated methodology to help local and regional authorities improve accessibility of urban areas by providing high-quality, sustainable transport to, through, and within the urban area. Essentially, it contains actionable guidelines for comprehensive and sustainable urban mobility planning.

The guidelines have gone through several evaluations, revisions, and targeted extensions since they were first published. The focus of SUMPs seems to be changing from an approach that would lead to the implementation of a transport system enabling sustainable mobility to a planning strategy leading to the decarbonization of the transport sectors. Today, the focus should be on specific SUMP measures or related policies, rather than on a comprehensive package of measures and interventions needed to deliver the zero-carbon target.

Starting in 2019, the CIVITAS SUMP-PLUS project helped towns and cities analyze their existing governance arrangements in an effort to bridge implementation gaps and break down the barriers preventing the development of effective strategies and policy actions. Most sites identified a lack of cooperation schemes and frameworks as a barrier, and these have now been substantially mitigated via a variety of engagement tools.

CIVITAS SUMP-PLUS also created six laboratories to equip “cities to develop the next generation of SUMPs and put mobility at the heart of sustainable urban transformation.”5 The labs are located in Antwerp, Belgium; Alba Iulia, Romania; Greater Manchester, UK; Klaipeda, Lithuania; Lucca, Italy; and Platanias, Greece.

The Manchester laboratory has clearly demonstrated the importance of stakeholder participation in achieving policy objectives.6 For example, a working group with members from both Transport for Greater Manchester and the National Health Service was a catalyst for the integration of cross-sector links into Greater Manchester’s transition pathway and the alignment of decarbonization strategies across health and transport sectors.7 It also drove an analysis of the alignment of healthcare and transport strategies and how these could be enhanced to form a joint, long-term transition pathway. The outcomes fed the development of Manchester’s Five-Year Environment Plan8 for health and transport decarbonization and harmonization of decision-making processes. Its health and transport decarbonization group is committed to delivering the Green Plan.9 In three years, stakeholders involved in this group will work together to monitor and update the plan.

Klaipeda successfully achieved the objectives laid out in its Economic Development Strategy and Action Plan10 on public transport renewal, in conjunction with the plan for the city development. Core and supporting measures for the redesign of the public transport network (particularly for the development of the planned bus rapid transit) have been identified, despite some initial difficulties due to the discussions on which core measure should be prioritized for the city’s future plans. Measures were accompanied by a specific financial strategy, including an estimate of implementation costs and related funding sources.

Platanias demonstrated that small and medium-sized cities can successfully develop a SUMP. The one created by the city helped it overcome mobility challenges, secure funding for sustainable mobility projects, and draft a plan that includes prioritization of actions and milestones to be achieved between now and 2035. Alba Iulia was also able to define a set of measures to be prioritized with related supporting measures.

New Opportunities for Cross-Governance Policies & Actions

Engagement tools and activities have the potential to improve organizational frameworks and promote cross-boundary cooperation among entities, as presented in CIVITAS SUMP-PLUS’s “Results of City Laboratories Evaluation.”11 The problem is that multilevel and cross-sectoral governance usually do not share common objectives, interests, or priorities, due to a lack of coordination and/or dialogue among the various groups. Strong coordination and collaboration at the local and regional levels, including cross-sectoral links, are needed.

European cities can overcome governance fragmentation (and its related uncoordinated policies and objectives) by (1) strengthening integration at the metropolitan and regional levels and (2) shifting specific transport competencies from the national level to regional and local levels. Regional governments can get closer to the citizens if municipality-based engagement strategies are successfully developed and pursued.

To achieve this, SUMPs should focus on integration and coordination with existing territorial planning and transport instruments at the local level while interfacing with the policies and plans of upper governance levels, including:

-

Cross-sectoral synergies with EU directives and national plans (e.g., transport, mobility, land use, infrastructure, digitization, energy).

-

Cross-sectoral synergies with regional plans and strategies (e.g., spatial development, environment, infrastructures).

-

Cross-sectoral synergies at the local and municipal level, such that mobility and transport plans are integrated with other planning tools. This integration should consider the societal and environmental goals set by the EU framework, as well as common objectives of the urban governance level. This will help ensure that plans for smart city strategy, local development, environment, air quality, and so on, are aligned.

Participatory structures can then be successfully delivered to facilitate bottom-up strategy developments as well as tailored local implementations of transport and mobility policies. This is a time-intensive process, due to the difficulties in mapping relevant actors, conducting co-creation events, and so on, but it’s critical for the citizen engagement needed for a successful decarbonization transition.

The sharing of experiences, through cross-fertilization exercises, networking activities, and knowledge sharing, can contribute to a common learning process on the transition pathway for the decarbonization and subsequent improvements. Ideally, policies and strategies will be developed at the local and regional level and then managed, interconnected, and coordinated with other European regions (see Figure 1).

Fostering Public & Private Cooperation

A key aspect emerging from the SUMP-PLUS project is the will to improve cooperation and integration between the public and private sectors. New forms of partnerships and business models have emerged as a main pillar in the transition toward decarbonized cities. The mobility market contains a broad spectrum of transport and logistics services, enabling technologies, and digital solutions that allows effective and efficient management of the various processes related to mobility, traffic, and public transport.

There are a number of design, planning, and implementation options available to operators and other actors (e.g., public/private organizations, planners, managers, value-added service providers, and users). For example, a variety of actors is assessing new ways to set up partnerships with the public sector. Cities are growing more comfortable letting public/private operators be proactive in the mobility context, provided the city sets the overall rules of the game (i.e., managing the city regulatory frameworks and responsibilities).

Antwerp and Lucca are good examples of cities that successfully developed a participatory process for collaborating with private companies. Through its Marketplace for Mobility, Antwerp has been very successful in encouraging private providers to launch in the city and pilot their services.12 In the past few years, several discussions about the various ways cities can support partnerships took place. The main drivers for this have been infrastructure provision, data sharing, and funding support.

Lucca set up an “innovation call” to select the most sustainable logistics companies (which it calls “Inspirers”) for participating in logistics roundtables and presenting innovative projects on sustainable logistics.13 Inspirers gained greater visibility, and this increased their willingness to behave sustainably and be involved in the discussion with an institutional representative. What’s more, the sustainability ranking is beginning to drive “old” companies to change.

Creating New Partnership Forms & Business Models

Collaborative and participatory framework(s) that enable various mobility actors to cooperate in offering innovative services play a strong role in the decarbonization of the transport sector. Integrated service bundles or solutions packages tailored to user groups go a long way in helping towns and cities successfully meet their decarbonization goals.

In Antwerp, these frameworks and solutions help meet the mobility and transport needs of workers, students, tourists, families with children, and the elderly. They enable reliable options for door-to-door journeys as well as practical alternatives to owning and/or using a car in the various transport environments of a functional urban area (metropolitan center, peripheral and suburban areas, and rural surroundings).14

In Lucca, the role of the local public authority, especially at the municipal level, is central not only for the legal responsibility of urban infrastructure and health but also at the planning level for identifying measures and facilitating engagement and dialogue among various stakeholders. This holds true at the day-to-day operation level as well for controlling urban logistics processes and ensuring compliance with defined rules related to environmental impacts (i.e., traffic congestion and pollution).

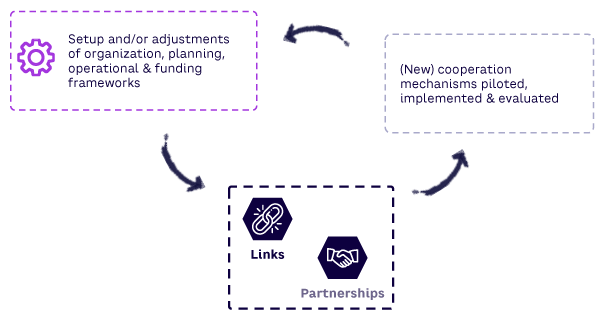

To better grasp the political and financial preconditions for success of urban mobility transition, it is important to flesh out various approaches to regulate shared mobility and logistics services (e.g., adaptive regulation, risk-based regulation, regulatory sandboxes) and to assess or adapt policy instruments (e.g., laws, directives, taxes, calls for bids) and financial models that have been shown to facilitate the adoption of new services (see Figure 2).

It is essential to analyze the regulatory and financial challenges linked to the implementation, monitoring, and enforcement of services and/or solutions (e.g., interoperability, cooperation models); the barriers for their deployment (e.g., existing legal frameworks); and the risks brought by the solutions (e.g., transport unaffordability or poor accessibility for vulnerable user groups) and adjust the regulatory and organizational frameworks accordingly.

City authorities should create a schedule for frequent assessment of the performance and achievements of the links and partnerships established. Based on the results, changes to existing frameworks can be confirmed or adjusted. The partnerships showing the most successful results can be promoted further.

Transitioning to Zero-Emission Cities

Cities across Europe are focusing on which mobility measures (for both people and freight) and measure-specific enabling actions are needed, given each city’s current legislative powers, institutional capacities, and financial resources. The time frame — net zero carbon by 2025 — will make it difficult to achieve the radical changes in transport and governance required. Cities must carefully evaluate the cross-sectoral constraints and requirements associated with mobility measures that will achieve this target, necessitating a transition based on a strategic vision for the city 10, 20, and 30 years from now (see Figure 3).

Decarbonization requires a focus on transport packages that effectively and efficiently reduce greenhouse gas emissions. SUMP development should align with climate objectives, so measures must be adapted accordingly (or dropped and replaced by other means to coherently ensure all SUMP objectives).15

It is essential to ensure long-term political buy-in and acceptance while implementing measures to start achieving long-term targets. For example, substantial measures should be implemented to create the public transport efficiency, affordability, and reliability needed for a sustainable city; this will require continuous funding during successive political administrations.

Upon agreeing on the vision, the city should thoroughly assess the policy, funding, and governance requirements needed to reach its long-term targets. City leaders must frequently evaluate whether the mobility strategies and policies they put in place are efficient (and socially acceptable) in delivering a transport system that meets environmental, social, and economic requirements; is cohesive with overall city development; and is sufficient to meet the net zero target.

During implementation of the transition strategy, governance structures and related arrangements should be set up, increasing the level of cooperation between city departments, local and regional entities, and other actors (public and private). This should result in a networked governance that periodically (e.g., every 10 years) realigns local planning objectives, partnerships, and frameworks with high-level policy goals set at EU, national, and regional levels.

With new frameworks in place, both private companies and public operators can be proactive, proposing new solutions for the mobility and logistics chain by filling gaps between their role in the service chain and the seamless integration of new solutions, contributing to the transition to a low/zero-carbon economy.

References

1 Jones, Peter, and Luciano Pana Tronca. “Policy Brief 6 — Delivering the Change: Developing a Comprehensive Implementation Strategy for Smaller Cities.” Horizon 2020 (H2020) CIVITAS SUMP-PLUS/EU, 6 February 2023.

2 Lorenzini, Andrea, Giorgio Ambrosino, and Brendan Finn (eds.). “Policy Recommendations for Sustainable Shared Mobility and Public Transport in European Rural Areas.” SMARTA/EU, March 2021.

3 Lorenzini, Andrea, and Brendan Finn. “Developing Pan-European Capacity at Local Level for a New Era of Sustainable Rural Mobility.” SMARTA-NET/EU, forthcoming 2024.

4 “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Together Towards Competitive and Resource-Efficient Urban Mobility.” EUR-Lex, Document 52013DC0913, EU, December 2013.

5 CIVITAS SUMP-PLUS website, accessed March 2024.

6 “Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2040.” Bee Network, accessed March 2024.

7 “Greater Manchester Path to Carbon Neutral.” Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA), accessed March 2024.

8 “Five-Year Environment Plan.” GMCA, accessed March 2024.

9 “The NHS Greater Manchester Green Plan 2022–2025.” NHS Greater Manchester, November 2023.

10 “Klaipėda 2030: Economic Development Strategy and Action Plan.” Klaipėda iD, March 2018.

11 Lorenzini, Andrea, Eleonora Ercoli, and Giorgio Ambrosino. “Results of City Laboratories Evaluation.” H2020 CIVITAS SUMP-PLUS Deliverable 5.3, MemEx, 2023.

12 “LIFE ASPIRE — Advanced Logistics Platform with Road Pricing and Access Criteria to Improve Urban Environment and Mobility of Goods.” EU, accessed March 2024.

13 Kishchenko, Katia, et al. “The Antwerp Marketplace for Mobility: Partnering with Private Mobility Service Providers as a Strategy to Keep the Region Accessible.” Transportation Research Procedia, Vol. 39, 2019.

14 Kishchenko et al. (see 13).

15 Schneider, Jochen, et al. “Topic Guide: Decarbonisation of Urban Mobility.” European Investment Bank (EIB)/Jaspers, December 2022.