AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 3

In recent decades, policy makers and local authorities have ignored the negative effects of predominantly car-oriented urban structures on people and the built environment. The design and distribution of transport infrastructure, as well as the modal split between various transport modes, play a critical role in determining overall health outcomes for society and individuals.1

The interaction between the built environment, mobility, and public health has a huge impact on the role of the city in shaping the well-being of its inhabitants.2 Simply put, the built environment (urban infrastructure, architectural design, and green and blue spaces) serves as a fundamental template for individual mobility patterns. The built environment, for instance, influences the daily lives of urban inhabitants in terms of walkability and accessibility to various daily amenities and modes of transport.3 The spatial dynamics of urban mobility are shaped by the configuration of the transportation system, while the design and safety of public spaces affect leisure time use in the urban landscape. Consequently, individual mobility behavior is a complex interaction between subjective perceptions and the objective availability of mobility options.4

Motorized private transport and air traffic remain the primary sources of pollutant emissions. The consequences of these emissions have a significant impact on both climate and human health. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution is one of the biggest threats to health, with 8.8 million people dying prematurely each year.5 Many cities are already experiencing heat islands due to densities and a lack of natural air exchange.6 Despite this, mobility patterns have remained largely unchanged in Germany over the past 20 years.7

Historically, the protection of human health has played an important role in urban planning and has even been one of the starting points for planned development. Since the Middle Ages, there have been fire-safety regulations and restrictions on the use of tanneries due to dense development.8 The Athens Charter, which aimed to improve hygienic conditions during the industrialization era, demonstrated the link between urban planning and health by focusing on improving ventilation and lighting in neighborhoods through the separation of work and living functions.9

Unfortunately, public health concerns are usually included too late or not at all in the planning process today.10 It seems that public health and urban planning have drifted apart. This lack of health-promoting structure means that many people do not have access to low-threshold, attractive opportunities for physical activity, including the simplest form of exercise: walking.11 Due to car-oriented street environments, walking is often limited and unsatisfying,12 and leaving health aspects out of the urban planning process has resulted in a wide disparity in health outcomes.13

The WHO’s Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach was adopted to bring back the link between urban planning and public health. It aims to integrate public health into all sectors and levels of public service. As a result, health issues such as prevention, health promotion, and healthcare are integrated into the disciplines of mobility and urban planning. The need to link public health and urban planning is also evident at the normative level, such as construction regulations.14

Sustainable urban development promotes a holistic approach that has led to an increase in the popularity of sustainable transportation options, such as walking and cycling. Although walking and cycling have predominantly positive effects on the environment and human health, these modes of transportation don’t fit into the daily mobility behavior of many people.

The concept of “walkability” describes neighborhoods that are easily accessible by foot or bike. This approach has a holistic impact, benefiting many areas. For example, more active lifestyles can reduce health costs and the incidence of noncommunicable diseases, such as heart disease and obesity.15,16

Active lifestyles and longer life expectancies also have a positive impact on the economy. For example, the German Institute of Urban Affairs found that employees who walk or cycle to work take a third fewer sick days per year and have a significantly lower body mass index.17 Similarly, pedestrian traffic occupies less space than motorized traffic, so areas such as streets or parking lots can be redesigned and transformed into recreational green spaces. The creation of green spaces and the reduction of motorized traffic help improve climate and air quality.18 A well-developed pedestrian infrastructure in the city center can also lead to more casual shoppers and increased purchases. City centers appear more attractive and safer to people when they are vibrant. Pedestrian areas are designed for strolling and lingering. Jan Gehl, a Danish architect and urban designer, put it this way: “Man is man’s greatest joy.”19

Data Example: Understanding Walkability

This article focuses on an empirical approach to identify relationships between the built environment and healthy mobility behavior to provide impetus for the development of active mobility interventions. Studies show that public health and the promotion of active and healthy mobility will be important for the design of future urban systems to reduce healthcare costs and create attractive urban districts. To plan strategic urban and transport systems, we must develop interdisciplinary databases and multilevel indicators.

An online survey was conducted in July 2021, with participants selected from an access panel weighted by age, gender, and residential location. The sample comprised 500 people 18 years of age or older living in Essen, Germany. The questionnaire consisted of 57 questions covering the following topics:

-

Sociodemographics

-

Health status

-

Mobility options

-

Physical activity patterns

-

Quality of the environment

-

Mobility behavior and activity radius

-

Attitude and mobility culture

-

Future vision

The study area was the city of Essen in the Ruhr region, the most densely populated part of Germany. Essen currently has 595,598 inhabitants living in 50 districts. Healthy and sustainable urban and mobility planning is becoming increasingly important in Essen, which suffers from the effects of car-dominated urban planning.20

The gender distribution of the data was 60.6% female and 39.4% male. The age distribution was diverse, with the majority in the 30-39 age group (23.6%). Most participants had completed high school (73%) and were employed (67%). Health status was good, with 44.6% reporting good health and 36.2% reporting very good health. The majority had a healthy weight (33.4%) or pre-obesity (25.6%). A significant proportion of the sample had a driver’s license (84.4%). In terms of mobility, participants reported an average of 3.8 trips per day, with an average of 5,882 steps taken on foot per day. The household vehicle fleet consisted mainly of cars (1.1 average) and bicycles (1.4 average).

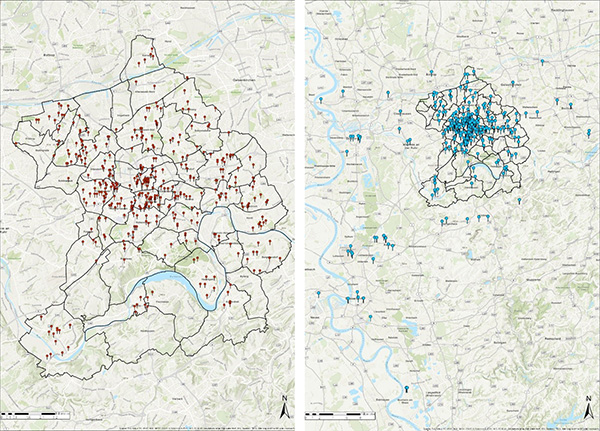

When respondents answered questions about their living environment, activity radius mapping was a key tool in understanding perceptions about and influences of the built environment. Participants placed pins on maps to mark their place of residence, workplace, and three preferred recreational areas. Coordinates were truncated to ensure anonymity.

The residential and work locations are shown in Figures 1 and 2 as examples. The distribution of places of residence shows a decline from north to south (see Figure 1). However, with the Baldeneysee (a lake in the south) and the urban forest (just above the lake), it is also clear that the southern part of Essen offers less residential space and serves primarily as a local recreation area. The majority of respondents live in Frohnhausen, followed by Rüttenscheid, Altenessen-Süd, and Südviertel. The information is concentrated in the northern and central parts of Essen, both in terms of residences and places of work. About 14% of the respondents work outside the city of Essen.

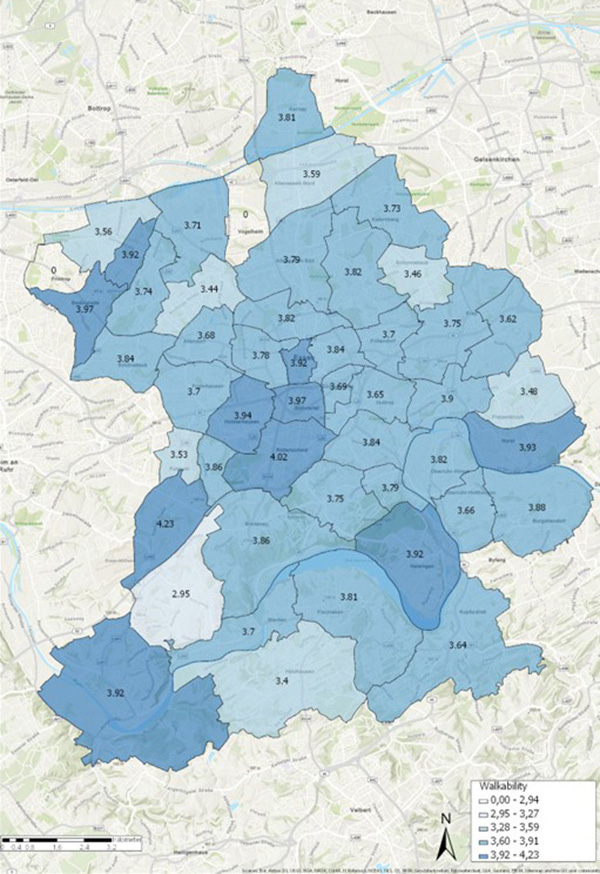

As stated, activity radius mapping plays an important role in identifying the influences of the built environment on people’s health and mobility behavior. This is also applicable to certain indices that can be used as indicators for necessary interventions in urban planning, such as walkability. Walkability can also be calculated by collecting data on the built environment alongside subjective perceptions.

This study collected items of objective walkability (14 items), subjective walkability (18 items), and accessibility (7 items) to quantify a representative walkability indicator. The items were questions about the walkability of the neighborhood (e.g., “How satisfied are you with the possibility of walking in your neighborhood?”; “How many minutes does it take to walk to your nearest transit stop?”). There were five predefined responses to these questions, each with a scale of 1 to 5. The scores were summed, and the mean was calculated to obtain the walkability index.

In our study, we calculated the walkability for every district in Essen. The results are shown in Figure 2. In the walkability index, 5 is the highest possible score. In this sample, the range of walkability is 2.95 to 4.24. The overall walkability for the city of Essen is 3.61, which is in the upper-half of the index, indicating that Essen has good overall walkability. The most walkable districts in Essen appear to be Byfang and Haarzopf. Rüttenscheid, Schuir, Heidhausen, and Bochold seem to have the worst walkability in this sample, but the index is still quite high, with 2.95 for Schuir and 3.40 for Heidhausen. The indices for Frintrop and Vogelheim could not be calculated because none of the study participants live in these areas.

Except for a few outliers, there is a decline from south to north, with the southern districts of Essen rating higher than the northern districts. This trend can also be seen in the standard land values of the city of Essen, which are often used as an indicator of attractiveness.21 Furthermore, neighborhoods located on the outskirts of a city tend to have lower walkability compared to those in the city center. This is because grocery stores, schools, and transit stops are often difficult to reach on foot or by bike in rural areas.

Another interesting piece of information is the data on the ratings of the individual indicators that make up the walkability index. The best rating for the city of Essen was given to the indicator “presence of sidewalks,” and the worst rating was given to the indicator “drivers exceeding the speed limit in the neighborhood.”

In the most walkable district, Byfang, several indicators received the highest score of 5, including “connectivity of streets” and “presence of green spaces.” The lowest score in Byfang was for “pedestrian crossings and traffic lights on busy streets.” In Schuir, the district with the worst walkability, the item “neighborhood as a place to live and feel good” got the highest rating, and the item “satisfaction with traffic noise in the neighborhood” got the worst.

Based on these findings, the walkability index is a valuable tool for improving the built environment relative to physical activity. As shown, it can measure walkability for an entire city and at the district level. The data set could also be used to analyze individual streets.

Walkability indices can also be used by real estate companies and public transportation operators. For example, accessibility impact can be determined based on property prices or the acceptance of public transport usage. Accessibility planning is also crucial for evaluating urban areas for investments or to estimate mobility justice. It could also be used by property owners to estimate the value of their property or explain trends in economic performance.22

The data shows that mobility and urban planning experts should take a more integrated approach to the design of public spaces. A built environment that promotes physical activity and good health can be linked to walkability and mobility behavior. Behavioral measures at the neighborhood level are an additional way to promote the desired change in mobility patterns and the integration of physical activity into everyday life.

References

1 Kopal, Kerstin, and Dirk Wittowsky. “The Healthy and Sustainable City — Influences of the Built Environment on Active Travel.” Sustainability, Vol. 15, No. 9, October 2023.

2 Giles-Corti, Billie, et al. “City Planning and Population Health: A Global Challenge.” The Lancet, Vol. 388, No. 10062, December 2016.

3 Kopal, Kerstin, and Dirk Wittowsky. “Urban Health as a Building Block of the Mobility Transition — How Does the Built Environment Influence Sustainable and Physical Activity-Promoting Behavior?“ In Towards the New Normal in Mobility, edited by Heike Proff. Springer Gabler, 2023.

4 Pyrialakou, V. Dimitra, Konstantina Gkritza, and Jon D. Fricker. “Accessibility, Mobility, and Realized Travel Behavior: Assessing Transport Disadvantage from a Policy Perspective.” Journal of Transport Geography, Vol. 51, February 2016.

5 Schulz, H., et al. “Breathing: Ambient Air Pollution and Health — Part I.” Pneumologie, Vol. 73, No. 5, 2019.

6 “Air Quality in Europe 2022.” European Environment Agency, 24 November 2022.

7 Zhong, Cheng, et al. “Evaluating Trends, Profits, and Risks of Global Cities in Recent Urban Expansion for Advancing Sustainable Development.” Habitat International, Vol. 138, August 2023.

8 Baumgart, Sabine. “Spatial Planning and Public Health: A Historical Linkage.” In Planning for Health-Promoting Cities, edited by Sabine Baumgart, Heike Köckler, and Anne Ritzinger. Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung (ARL) [Academy for Space Research and State Planning], 2018.

9 Kistemann, Thomas, and Anne Ritzinger. “Models of Health-Promoting Urban Development.” In Planning for Health-Promoting Cities, edited by Sabine Baumgart, Heike Köckler, and Anne Ritzinger. ARL, 2018.

10 Frinken, Matthias. “Health in Spatial Planning.“ PLANERIN, Vol. 4, August 2018.

11 Schmidt, J. Alexander, et al. “Walkability in Practice Overall Report: Walk Audits in Three Cities in North Rhine-Westphalia.” Institute of Urban Planning and Development, University of Duisburg-Essen, October 2018.

12 Gehl, Jan. Städte für Menschen [Cities for People]. JOVIS, 2015.

13 “Promoting Active Mobility in Old Age: A Working Aid for Cooperation Between the Municipal Planning and Construction Administration and the Public Health Service in Small and Medium-Sized Towns.” Institute of Public Health and Nursing Research, University of Bremen/Technical University of Dortmund, 2018.

14 The 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion, Helsinki, 2013. World Health Organization (WHO), accessed March 2024.

15 Bauer, Uta, et al. “It’s Possible! Outlines of a Nationwide Pedestrian Traffic Strategy.” Umwelt Bundesamt [Federal Environment Agency], October 2018.

16 Tran, Minh-Chau. “Walkability as a Component of Health-Promoting Urban Development and Design.” In Planning for Health-Promoting Cities, edited by Sabine Baumgart, Heike Köckler, and Anne Ritzinger. ARL, 2018.

17 Bauer et al. (see 15).

18 Tran (see 16).

19 Gehl (see 12).

20 Dahlbeck, Elke, et al. “Analysis of the Historical Structural Change in the German Hard Coal Mining Ruhr Area (Case Study).” German Environmental Agency, January 2022.

21 BORIS-NRW website, accessed March 2024.

22 “About Walk Score.” Walk Score, accessed March 2024.