AMPLIFY VOL. 38, NO. 2

With biodiversity loss emerging as a critical concern, the urgency to address climate resilience has companies searching for solutions. Even as they recognize the importance of integrating nature positive actions into their sustainability strategies, many companies struggle with operationalizing nature positive actions.

Should new positions and programs be created or pilot projects implemented? As companies explore what being nature positive means, many find that existing compliance, conservation, and stewardship certifications already contribute to positive nature and biodiversity.

In this article, we explore how leveraging established nature positive programs can enhance corporate sustainability efforts. Here, we define “nature positive programs” as formalized government-led conservation efforts, proactive industry standards, or data-driven or science-based environmental certifications. These programs help businesses align their practices with global biodiversity goals, improve ecosystem restoration, and reduce environmental risks. By engaging with existing nature positive programs, companies can contribute to habitat creation and other positive environmental outcomes.

The Critical Role of Nature & Biodiversity in Business Sustainability

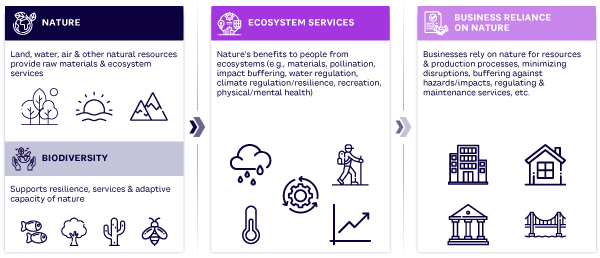

Everything we have as a society (including businesses) relies on nature. Nature comprises the lands, waters, air, and other natural resources that provide raw materials and ecosystem services. Biodiversity constitutes the ecosystems and species comprising nature, which create resilience and enhance many ecosystem services. Together, nature and biodiversity support the ecosystem services, raw materials, and support networks we rely on for all facets of life (see Figure 1).

Nature and biodiversity loss poses a significant threat to ecosystems and human well-being. Declines in biodiversity disrupt ecosystems vital to food security, resource availability, climate regulation, and pest/disease control.

Global frameworks like the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) emphasize the need for urgent action to address biodiversity loss.1 As recently stated at the 2024 United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP16), companies play a crucial role in achieving these goals by adopting nature positive practices that contribute to conservation and sustainable use of natural resources.2

Increasing Demand for Nature-Related Disclosures

Not surprisingly, given business reliance on nature and biodiversity, the financial sector is acutely interested in understanding and addressing biodiversity risk. Investors, customers, and regulators are demanding greater transparency regarding corporate impacts on nature.

Disclosure frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), and others have expanded their nature-related disclosures. These disclosures help businesses identify and manage their environmental impacts with the goal of mitigating financial risks, enhancing company reputation, and improving competitiveness. By reporting on nature-related metrics, companies demonstrate their commitment to sustainability goals (including being nature positive) and build trust with stakeholders.

The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) provides an assessment framework for businesses to identify, assess, and manage nature-related risks and opportunities. TNFD’s Locate-Evaluate-Assess-Prepare (LEAP) planning approach helps companies understand how their operations depend on and impact nature. By integrating TNFD assessments into their sustainability planning, companies can mitigate risks from nature and biodiversity loss, such as operational exposures, supply chain disruptions, and regulatory penalties, while capitalizing on opportunities like species conservation, resource efficiency, and new market development.

Species Loss as a Conservation Concern & Business Risk

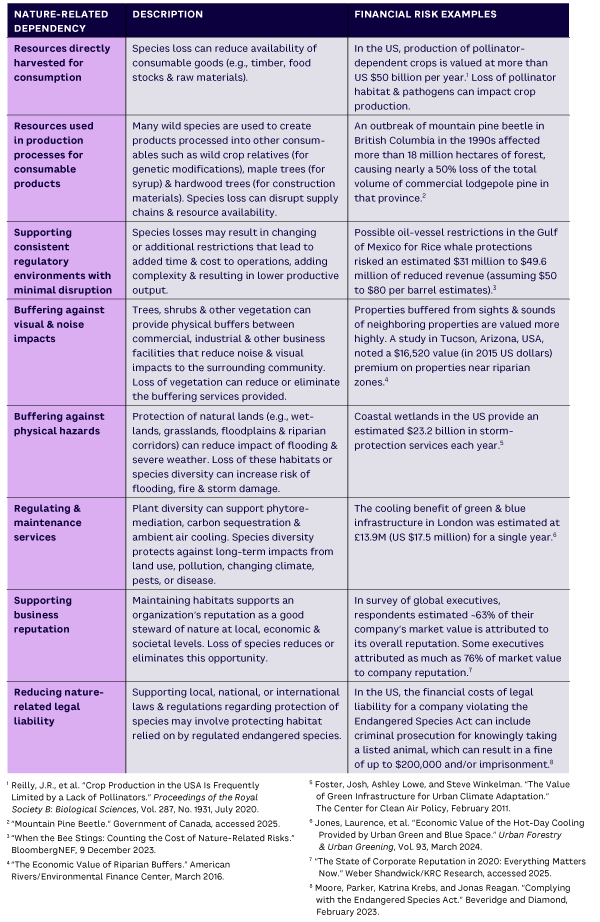

According to WWF “2024 Living Planet Report,” there has been a 73% decline in global wildlife populations in just 50 years (1970 to 2020).3 This loss poses significant risks to businesses, including direct impacts on the bottom line. Loss of pollinators like bees can directly affect agricultural productivity. Decline of fish stocks can impact the seafood industry. Companies that do not directly rely on individual species may also be impacted by biodiversity loss in more nuanced ways (see Table 1).

When considering these risks in light of their own operations, companies increasingly recognize that species declines are not just an ecological concern but a business risk. Proactive conservation efforts can help mitigate these risks, ensuring the sustainability of natural resources that businesses depend on. Reporting mechanisms like those previously mentioned help companies track and communicate how nature affects their business as well as what actions they are taking to reduce ecological and financial risks.

Addressing Biodiversity via Existing Nature Positive Programs

Companies exploring their nature-related dependencies or impacts (and the corresponding risks and opportunities) will find a myriad of programs and tools to support their needs. This lets businesses explore new frontiers while rethinking how their existing operations and risk mitigations can help reduce nature risks. Available tools include:

-

TNFD’s LEAP planning approach — helps companies understand how their operations depend on and impact nature

-

Exploring Natural Capital Opportunities, Risks and Exposure (ENCORE) — helps financial institutions and companies take initial steps to understand their dependencies and impacts on nature4

-

The Natural Capital Protocol — helps companies measure and value their impacts on natural capital, which can include aspects of biodiversity that support capital dependencies5

-

The Science Based Targets for Nature (SBTN) — guides businesses in setting measurable biodiversity goals6

With risks and opportunities identified, a company can consider how to address its business concerns. Because biodiversity loss has been an ongoing concern over the past few decades, many programs have already been developed by government agencies, not-for-profit conservation organizations, private investors, and public-private partnerships to address biodiversity loss and support nature positive actions. However, this rush to fill a market need has caused poor results in some cases and criticisms of greenwashing in others. Companies engaging in nature positive programs must carefully choose where to invest time and money to avoid reputational risks. Third-party audits and verification programs are needed to reduce the risk of underperforming biodiversity programs.

Many third-party verification programs are already in place. These initiatives provide frameworks and tools for businesses to integrate conservation into their operations. Below, we highlight a few such programs available to the energy and transportation sectors via the Rights-of-Way as Habitat Working Group (ROWHWG), which administers voluntary conservation agreements, convenes industry peer exchanges, and supports other nature-related sustainability efforts.7 By participating in programs like these, companies can enhance their sustainability strategies and contribute to conservation efforts.

Conservation Agreements

Conservation agreements are voluntary commitments by businesses to protect and restore natural habitats. Unlike offset mitigation, these agreements are developed cooperatively to create a net benefit in which the benefits to a species or its habitat clearly outweigh the impacts created by the business. Mitigation agreements focus on minimizing negative impacts on biodiversity, often through habitat restoration or creation. Net-benefit agreements go beyond mitigation to enhance biodiversity through proactive conservation actions.

These agreements can take various forms. In the US, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) allows voluntary agreements that “enhance the survival” of species at risk of extinction in exchange for regulatory predictability. These take various forms based on the scope, legal status of a species, and degree of benefit created. Across the US and Europe, other conservation agreements take the form of stewardship agreements, conservation easements or leases, or designated use or payment models.8

Conservation agreements may be tailored to the needs of local communities and regulations.9 Conservation International has 4,000 conservation agreements in 19 countries that collectively protect 4.4 million acres (1.8 million hectares). Comparing approaches and a company’s ability to commit to action is important when choosing the most effective strategy for nature-related sustainability goals.

Starting in October 2017, ROWHWG, University of Illinois Chicago (UIC), led a national, multi-sector cooperative effort to develop a voluntary conservation agreement for the monarch butterfly.10 Representatives from across the energy and transportation sectors collaborated to develop a conservation agreement that encourages the adoption of conservation measures to create net benefits for the monarch butterfly. The unprecedented effort and agreement span the contiguous 48 states of the US. As of January 2025, it was the single-largest voluntary conservation agreement in the US, with nearly 70 participants enrolled in the program committing to more than 1.1 million acres (more than 445,000 hectares) of habitat conserved.

Companies engaging in this program have leaned on their conservation agreement commitments to support their nature-related sustainability claims because of its third-party verification mechanisms. The agreement requires that annual habitat monitoring and reporting be sent to UIC, which administers the program. UIC reports on the conservation delivered through the program and its partners to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which authorizes the program via a permit under the ESA. This creates a robust third-party verification structure that is scientifically defensible and simple to implement. As a result, companies like NiSource, Duke Energy, Phillips 66, and TC Energy all leverage the agreement in their sustainability reporting.11-14

A new voluntary conservation agreement is being developed by UIC in partnership with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, and dozens of industry and conservation organizations. It encourages conservation for 11 species of at-risk bumble bees native to parts of the US. Like the one for monarchs, the agreement formalizes company commitments to conservation in exchange for regulatory predictability and flexibility under the ESA. Mirroring the tracking, monitoring, and reporting requirements of the monarch agreement, the bumble bee agreement will further strengthen the biodiversity-protection claims made by companies enrolled.

In addition to US-based agreements, international conservation agreements offer valuable models for businesses committed to nature positive practices. For example, the Business and Biodiversity Offsets Programme (BBOP), a global initiative, has developed various frameworks to support companies in achieving net-positive biodiversity outcomes.15

Another notable example is Brazil’s Atlantic Forest Restoration Pact (Pacto pela Restauração da Mata Atlântica), which is a collective, voluntary conservation agreement.16 This initiative involves businesses, nongovernmental organizations, and government bodies working together to restore and protect the critically endangered Atlantic Forest. Participating companies commit to protecting and restoring key areas of the forest, supporting habitat restoration, and achieving long-term biodiversity conservation goals. The pact provides a framework for companies to make biodiversity commitments that contribute to regional and global conservation efforts.

Tools for Biodiversity & Sustainability Claims

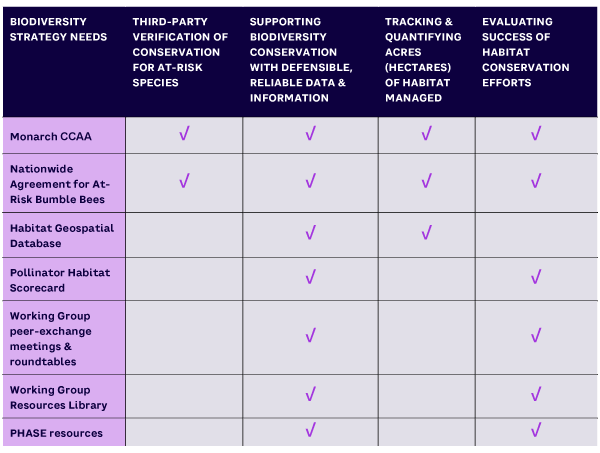

In addition to conservation agreements, other tools are widely available to support biodiversity. In particular, companies wanting to avoid greenwashing allegations often seek tools that offer independent confirmation of positive outcomes. These include:

-

Conservation verification by government agencies, conservation organizations, or another third party — allows independent confirmation of actions and outcomes.

-

Defensible, reliable data and information — help dispel negative perspectives. By conducting direct research or using appropriate indirect inferences from related studies, a company can ground its outcomes in science-backed information.

-

Tracking and quantifying acres (hectares) of managed habitat — simple, verifiable method of demonstrating habitat commitments. Using satellite and unmanned aerial vehicle data collection, this method produces a cost-effective metric that can be used across many programs.

-

Third-party methods — help companies evaluate the success of habitat conservation efforts. These include scorecards, benchmark assessments, and habitat-evaluation indices that use science-based and transparent methodologies to assess success.

These tools may be used individually or in concert, depending on company needs and goals. For example, ROWHWG offers open source tools to support biodiversity and sustainability claims for the energy and transportation infrastructure sectors. (Tools and resources are available to other sectors via organizations such as Conservation International, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Wildlife Habitat Council, and the WWF).

ROWHWG tools include:

-

The Habitat Geospatial Database — lets users track location-specific data on habitat quality and conditions for effective biodiversity management

-

The Pollinator Habitat Scorecard — helps companies evaluate and improve habitat suitability for pollinators in a given area

-

Working Group peer-exchange meetings and roundtables — facilitate collaborative learning and sharing of best practices among industry professionals

-

The Resources Library — offers a centralized hub of guidance documents, case studies, and tools to support habitat conservation efforts

-

The Pollinator Habitat Aligned with Solar Energy (PHASE) study — provides specialized tools for integrating pollinator habitats into large-scale solar energy development sites.

These are adaptable and can help inform decision-making, document habitat outcomes, and support sustainability reporting (see Table 2).

Engagement Examples

Effective stakeholder engagement is essential to the success of nature positive programs. Examples of successful engagement include partnerships with conservation organizations and other academic institutions, community involvement in habitat-restoration projects, and collaboration with government agencies. These engagements help build trust and support for corporate sustainability initiatives, ensuring long-term success and positive outcomes. The examples listed in Table 2 are the products of effective engagement between conservation and industry stakeholders and have contributed to large-scale conservation across the US.

Identifying & Leveraging Existing Nature Positive Programs

Recognized by TNFD as an example for nature positive outcomes, ROWHWG highlights how cooperative approaches can enhance biodiversity and support nature positivity, encouraging companies to leverage such partnerships in their sustainability efforts.17 Other conservation, industry, and academic-led programs include the Right-of-Way Stewardship Council, Utility Arborist Association, Wildlife Habitat Council, and Xerces Society’s Bee Better certification program.

Identifying the best-aligned program can be a challenge. Using observations from ROWHWG, we recommend companies navigate the various programs and opportunities available by:

-

Identifying programs that help address nature-related business risks. Engaging with programs that address aspects of physical and transitional risks can reduce company risk.

-

Participating in programs offering cross-sector and peer exchanges. Sustainability programs help companies benchmark their efforts against others and foster new knowledge/research connections by allowing them to engage with industry peers and those in other sectors with similar objectives. Programs that facilitate this type of engagement can be a long-term asset.

-

Leveraging third-party agreements and certifications that demonstrate nature positive outcomes. Many companies have created their own biodiversity metrics and frameworks to demonstrate nature positivity. Although this approach offers the most adaptation, it forces companies to justify findings and opens them up to real or perceived greenwashing accusations. By engaging in third-party conservation agreements/certifications (or leveraging their resources), companies can prove that defensible, robust systems are in place to support their nature positive claims. This approach also enhances the transparency and accountability needed to meet investor/stakeholder expectations and regulatory requirements.

Conclusion

Collaborative efforts like ROWHWG serve as models for nature positive outcomes and enhanced sustainability reporting. By leveraging existing nature positive programs, businesses can contribute to global biodiversity goals, mitigate risks, and engage communities then leverage these opportunities for sustainable growth. Integrating nature positive actions and partnerships with established conservation programs into corporate sustainability strategies is not only beneficial for the environment, it’s good for business.

References

1 The Kunming-Montreal GBF was adopted during the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 15); see: “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.” Convention on Biological Diversity, 1 October 2024.

2 Pervan, Josip. “CBD COP16 Signals a Growing Momentum Towards Integrating Biodiversity Considerations into All Sectors of the Economy and Society.” World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), 14 November 2024.

3 “2024 Living Planet Report: A System in Peril.” WWF/Zoological Society of London (ZSL), 2024.

4 Exploring Natural Capital Opportunities, Risks and Exposure (ENCORE) website, 2025.

5 “Natural Capital Protocol.” Capitals Coalition, accessed 2025.

6 ”Biodiversity.” Science Based Targets Network (SBTN), accessed 2025.

7 Rights-of-Way as Habitat Working Group (ROWHWG) website, 2025.

8 Pons, Joan. “State of the Art and the Potential for Further Development of Conservation Agreements as Private Land Conservation Tools.” European Networks for Private Land Conservation (ENPLC), 2023.

9 Kane, Cassandra. “What on Earth Is a ‘Conservation Agreement’?” Conservation International, 20 February 2018.

10 ”Nationwide CCAA for Monarch Butterfly.” ROWHWG, accessed 2025.

11 “Creating Shared Value: NiSource 2024 ESG Report.” NiSource, 2024.

12 “Investor Relations.” Duke Energy, accessed 2025.

13 “2024 Sustainability and People.” Phillips 66, accessed 2025.

14 “Report on Sustainability.” TC Energy, July 2024.

15 “BBOP Biodiversity Offsets.” Forest Trends, accessed 2025.

16 “Atlantic Forest Is Declared UN World Restoration Flagship.” WWF, 13 December 2022.

17 “Additional Sector Guidance — Electric Utilities and Power Generators.” Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), July 2024.