AMPLIFY VOL. 37, NO. 8

We genuinely care about developing leaders who can be forces for positive change. In our leadership development programs (LDPs), whether regular degree-seeking or company programs, we begin by encouraging participants to discover and commit to their personal purpose by formulating an “I Will” statement that connects their personal ambitions with the challenges of today’s society.1

We do not impose any goals on participants, allowing them to identify and dedicate themselves to a personal mission by articulating their I Will statement, which links their personal aspirations with the challenges of contemporary society. In this manner, participants are invited to discern how they can contribute to society in a distinctive manner. It has been shown that goals grounded in intrinsic motivation will have a more enduring and meaningful impact on society.

Perhaps more pertinent than what (i.e., personal purpose aimed at societal challenges) we aim to develop is how we aim to develop it.2 A guiding principle to our developmental approach is being evidence-based.3 This involves a process of clear theoretical and pedagogical foundations that help steer the process and ongoing evidence collection (e.g., survey measures, long-term effects, randomized trials). This creates a feedback loop that lets us evaluate whether we develop leaders who can become positive change agents (and to course correct when we don’t).

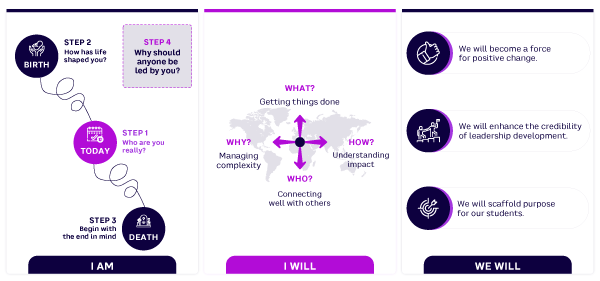

This article contains lessons learned from attempting to develop purpose-driven leaders over the past decade. Our lessons are structured around three steps (see Figure 1) labeled as I Am (discovering purpose), I Will (committing to purpose), and We Will (engaging others with your purpose).

Discover Your Purpose: I Am

Genuine purpose has the potential to give a career, and even one’s life, meaning and direction, but it has turned into a buzzword with various interpretations. At the Rotterdam School of Management (RSM), Erasmus University, the Netherlands, we ground purpose in one’s authenticity (one’s assumed true self) and thus one’s intrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic motivation is important because it offers more enduring and dedicated motivation than any extrinsically imposed purpose.4 Although discovering and understanding some sense of purpose in life has been a longstanding human quest, these crucial acts of sensemaking have become increasingly more pertinent and difficult.5 Influential thinkers like Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor refer to a feeling of alienation and a sense of disorientation and insecurity due to the breakdown of great frames of reference in society.6,7

At the same time, this vacancy of structural or societally driven purpose has resulted in a thriving purpose “market.” We are inundated by a variety of potential purposes that are easily lost as we turn our attention to the next.

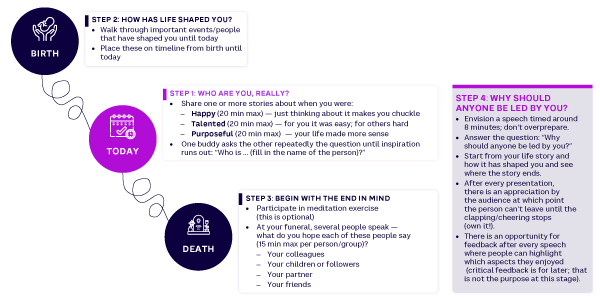

When we connect purpose to authenticity, it is stably connected to the self, and that self can be meaningfully connected to societal challenges. In Figure 2, we highlight the three-step exercises we use to help people discover their authentic purpose: (1) discovery (2) tension resolution, and (3) narrative building.

The first step is for people to discover their personal purpose. We often assume that success in life is grounded in what society or others expect from us rather than being intrinsically grounded. Our leadership exercises aim to surprise people about what truly gives them purpose.

For instance, the first exercise asks people to share stories of happiness, talent, and meaning, with the intention of defying preconceived notions people may have about purpose. What’s important is creating sufficient space for mind-wandering (participants go out in nature to really let things sink in), allowing them to discover what emerges from within themselves rather than what is constructed.8

The next step is to induce and then resolve tensions. We are often unaware of the things holding us back. Through exercises like the near-death meditation (see Figure 2) we intentionally induce a tension between one’s current life and the legacy one wants to leave behind.9 We make sure it is not just a cognitive exercise (e.g., “What would people say at your funeral?”) but a well-guided meditation that helps people experience being forced to abandon the people, projects, and aspirations they fundamentally value. Our research shows that through tension we create epiphanies — aha moments that help us connect to our purpose.10

Without this deep and personal challenge, our fundamental reasons to live remain dormant until they are triggered and resolved in a psychologically safe environment. We cannot underscore this enough: our research indicates that discomfort can accelerate development, but only when people can handle this discomfort.11 In other words, this near-death exercise comes with a “don’t try this at home” warning (unless there is a highly supportive setup with qualified individuals running the exercise).

The third step is to build a narrative.12 We ask people what moments and people have contributed to the person they are today and encourage them to answer the question: “Who are you, and how do you lead in life?” We encourage people to speak from the heart and refuse to give them time to prepare. That may seem daunting, but we find it increases the vulnerability of (and the personal connection to) the speech. What seemed like disconnected events are suddenly strung together into a melody that narrates the person’s leadership.

Commit to Your Purpose: I Will

Past leadership development programs have shown us that some of the knowledge or insights we offer to participants are fleeting unless participants can commit (i.e., targeted internalization and utilization) to the learnings.13

Developmental programs don’t always change behavior during the program (this would defy what we know about the slow pace of human change); instead, they prepare people for the hard work of enacting change later on.14 Indeed, the work on experimentation (flexing) encourages people to set behavioral intentions to learn.15

Intentions are one of the strongest predictors of behavior, especially when they are shared publicly through a powerful I Will statement, including your picture on our wall or in the form of an I Will speech (think TED Talk).16,17 We can testify to the power of a public outing that expresses and claims a specific leadership ambition with some audacity: article coauthor Hannes Leroy’s I Will statement is: “I will enhance the credibility of leadership development.”

In the second stage, we work with participants for about a year on the implementation of their plans. Specifically, we have participants address the following questions in a stepwise manner (taking one step forward every three months):

-

What needs to be done? Get clear on your vision, from “we will be the first to land on the Moon” thinking to the realistic subgoals toward success.18

-

Who are the stakeholders who can help (or hinder) your plan and how/when will you approach them?

-

How can you implement your plan, including navigating through roadblocks and stepping stones?

-

Why would people pursue this long after you are gone? How can you make this independent of you as a driving force?

We frequently challenge participants to address each of these elements and offer group sessions (and thus a shared community) with a team coach to help build toward success. We also offer individual mentorship if participants hit a dead end or have personal issues that cannot be dealt with in a group format.

Key to these shared moments and touchpoints is accountability (not just support). Participants know these are not the key developmental moments (those happen between sessions) but are about reporting, resolving issues, reflecting, and taking the next concrete steps in the development journey. This is an accountability group first and a support group second.

After one year of hard work by participants, we hold them accountable for product delivery. We want participants and the community they serve (organizations, spouses, and friends) to see the fruits of their labor, not just in idea format, but in viable entrepreneurial projects. Other than the intrinsic anchoring that fuels the passion to pursue these ideas, we believe our help in guiding ideas to maturity and viability is what sustains these projects both extrinsically and intrinsically.

Engage Others with Your Purpose: We Will

In the first stage, people discovered their purpose, and with this came a sense of responsibility in its etymological meaning: the capacity to respond to a deeper calling. In the second stage, the element of accountability complemented the discovered responsibility. The third stage is about engaging others or the embeddedness of the leadership project in a specific community.

Discovering your purpose and committing to it is an act of personal leadership, but it is not yet an act of leading others. In this step, we encourage people to connect their personal vision to the vision of others, to the organization they work for, or to larger societal problems. This requires putting one’s own perspective into a larger whole.

This is a crucial step because we often find that LDPs, especially ones that focus on purpose, lead to people quitting their job, leaving their spouses, and/or disrupting their current life in the name of authenticity and purpose.19

Authenticity is important, and we try to cultivate it in the first two steps, but in this last step, we contextualize authenticity within a larger whole. We ask individuals to not only come up with an I Will speech but to work toward a We Will speech. How can they convince others to align with their personal vision and mission? How can they connect their intrinsic motivation to the intrinsic motivation of others?

Our research indicates four key elements for an effective We Will speech:

-

Competence. Is the goal or objective believable and achievable? To what extent has the participant come up with a realistic plan that builds on their competencies?

-

Warmth. Does the participant have the best interest of the followers at heart? Consider the extent to which the participant can take the perspective of the follower and have that reflected in his or her speech.

-

Charisma. Does the participant appeal to others with the vision? To what extent can the participant convincingly demonstrate that they own the vision and are the right person for the job?20

-

Integrity. Does the participant put the vision into practice? Here, we consider the extent to which the participant can articulate the values behind the vision and put them into action.

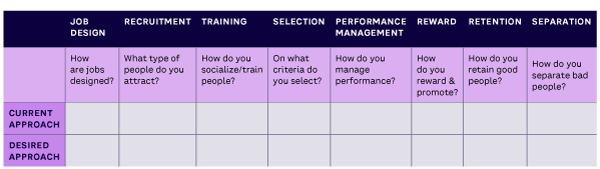

Of course, words alone are insufficient to implement the vision, so we ask participants to simultaneously work on the design characteristics that support their vision. In Figure 3, we show a deceivingly simple exercise to follow the work done in the previous steps.

The exercise asks about the current and desired steps on key aspects of managing people, but it requires participants to take a long, hard look at how to reengineer structure to match their purpose. It is usually a team or organization being reengineered, but it could easily be applied to a society.

In this stage, we make it clear how leaders, after discovering individual purpose and meaning and becoming willing to be held accountable, must translate their vision to an organizational reality. In this way, they become the architects of a structural blueprint for their vision and influence others, so they experience the positive spiral boosted by the interaction of responsibility, accountability, and community.21

In this way, leadership development moves beyond leader development, creating a ripple effect that allows others to see their unique contribution while connecting their daily life or work with timeless aspirations, whether on an organizational or societal level.

Conclusion

Scaffolding purpose is not easy, as it involves the complex task of connecting one’s personal self to societal demands. In this article, we outlined three steps toward scaffolding purpose, with practical tools available for a wider audience to adopt or adapt. We hope that, beyond offering these tools, people will pick up on the lessons we have learned over time on how to effectively set people on a track toward purpose.

References

1 “I Will.” Rotterdam School of Management (RSM), Erasmus University, accessed August 2024.

2 Leroy, Hannes, Moran Anisman-Razin, and Jim Detert. “Leadership Development Is Failing Us. Here’s How to Fix It.” MIT Sloan Management Review, 6 December 2023.

3 Leroy, Hannes L., et al. “Walking Our Evidence-Based Talk: The Case of Leadership Development in Business Schools.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, Vol. 29, No. 1, January 2022.

4 Van den Broeck, Anja, et al. “Beyond Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: A Meta-Analysis on Self-Determination Theory’s Multidimensional Conceptualization of Work Motivation.” Organizational Psychology Review, Vol. 11, No. 3, April 2021.

5 Weick, Karl E. Sensemaking in Organizations. Sage Publications, Inc., 1995.

6 Taylor, Charles. The Ethics of Authenticity. Harvard University Press, 2018.

7 Taylor, Charles. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Harvard University Press, 1992.

8 Dane, Erik. “Suddenly Everything Became Clear: How People Make Sense of Epiphanies Surrounding Their Work and Careers.” Academy of Management Discoveries, Vol. 6, No. 1, April 2020.

9 Higgins, E. Tory. “Self-Discrepancy: A Theory Relating Self and Affect.” Psychological Review, Vol. 94, No. 3, 1987.

10 Dane (see 8).

11 Vongswasdi, Pisitta, et al. “Uncomfortable but Developmental: Mindfulness Moderates the Impact of Negative Emotions on Learning.” Academy of Management Learning & Education, forthcoming 2024.

12 Zheng, Wei, Alyson Meister, and Brianna Barker Caza. “The Stories That Make Us: Leaders’ Origin Stories and Temporal Identity Work.” Human Relations, Vol. 74, No. 8, March 2020.

13 Day, David V., and Lisa Dragoni. “Leadership Development: An Outcome-Oriented Review Based on Time and Levels of Analyses.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, Vol. 2, 2015.

14 Hannah, Sean T., and Bruce J. Avolio. “Ready or Not: How Do We Accelerate the Developmental Readiness of Leaders?” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 31, March 2010.

15 Ashford, Susan J. The Power of Flexing: How to Use Small Daily Experiments to Create Big Life-Changing Growth. Harper Business, 2021.

16 Ajzen, Icek. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 50, No. 2, December 1991.

17 Leroy, Hannes. “I Was Never Trained for This!” TEDxErasmusUniversityRotterdam, October 2020.

18 Carton, Andrew M. “‘I’m Not Mopping the Floors, I’m Putting a Man on the Moon’: How NASA Leaders Enhanced the Meaningfulness of Work by Changing the Meaning of Work.” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 63, No. 2, June 2017.

19 Leroy, Hannes, et al. “The Different Ways of Being True to Self at Work: A Review of Divergence Among Authenticity Constructs.” Human Relations, forthcoming 2024.

20 Antonakis, John, Marika Fenley, and Sue Liechti. “Can Charisma Be Taught? Tests of Two Interventions.” Academy of Management Learning & Education, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2011.

21 Carton (see 18).